|

Just like we want to identify the underlying needs of students before deciding how to respond to student behavior, we want to do the same for the system. Before we rush to action to solve an identified problem, we need to truly diagnose the challenge. To inform our diagnostic process, let’s use some of the core concepts from The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World by Heifetz, Linksy, & Grashow. Adaptive leadership is specific to adaptive challenges, the ones that cannot be solved with a quick fix.

How do I know my school is dealing with an adaptive challenge? Heifetz and colleagues contrast adaptive challenges with technical challenges. Whereas a technical challenge can be addressed by sharing new information, perhaps holding a Professional Development session for all staff, adaptive challenges require much deeper work. One indicator of an adaptive challenge in schools is repeated failure. All the PD you have thrown at the problem is not working. Another indicator is looking to the leader (e.g., principal or superintendent) to solve the problem. When the same person(s) has been trying to solve the problem without success, it is time to bring in other stakeholders. Another indicator you are dealing with an issue that goes deep is when you see “disproportionate reactions to proposals”. For example, if asking a teacher to attend a staff meeting about racism leads to that teacher yelling or crying, there is something deeper going on. The essence of adaptive challenges can be captured in this sentence of Heifetz, Grashow, and Linsky’s book: “Adaptive challenges are typically grounded in the complexity of values, beliefs, and loyalties rather than technical complexity and stir up intense emotions rather than dispassionate analysis,” (Loc. 1283). How might adaptive challenges show up in my school? The authors identify four main types of adaptive challenges that often overlap with one another. See if you can identify any of these within your school and need adaptive leadership.

My school has an adaptive challenge we need to tackle. What can I do about it? Set up structures of shared leadership. The first step is recognizing you cannot do this work alone. Shared leadership structures are powerful because they are not temporary solutions. They are not ad-hoc committees, separate from the rest of the organization. Shared leadership is the heartbeat of the organization. It is how all decisions are made. Shared leadership is more about the how than the what. By setting up ongoing mechanisms for all stakeholder voices, shared leadership systematizes the process of diagnosis for adaptive challenges. You do not need to start from scratch each time you need to collect data or stakeholder experiences on one specific topic. The system will already exist. Furthermore, shared leadership as a form of governance is preventative rather than reactive. Much of the conversation in education is about fixing problems or policies that already exist. Certainly, this is important and necessary work. However, in improving our decision-making and policy creation processes, we can reduce our future needs to react to poor decisions and policies because we are more likely to get it right the first time. For more details on how to set up the structures of shared leadership, read this blog post. Each stakeholder is going to approach the situation with a unique set of values, loyalties, fears, and desired outcomes. To effectively engage stakeholders in the work of tackling an adaptive challenge, leaders must “diagnose the political landscape.” To do this, we can ask each stakeholder (or ask representatives of stakeholder groups as long as the system of representation is effective):

Once you have gathered all of this information, you may want to identify common points of connection across stakeholder groups. Heifetz and colleagues call these “hidden alliances” as groups who may initially seem in opposition to one another’s proposed solutions may have a shared value or desired outcome that when illuminated can help them work together. To help you get started on the process of diagnosis, I’ve made a mini workbook for you with activities and guiding questions.

0 Comments

This year, paying attention to students’ social and emotional needs is more important than ever. There are a lot of SEL sites and strategies to support educators in doing this work. BetterLesson’s bank of SEL strategies is a great resource for teachers looking to explore new practices.

Let’s say you implement a bunch of SEL strategies, but you still have a student say or do something that harms another person in the class. Keeping the importance of students’ social and emotional health in mind, we want to respond in a way that restores the harm done. Restorative conversations helped me address the harm done in my class far more effectively than consequence charts or punitive measures. It also helped me empathize more with students—the students harmed the students who harmed someone else, and also students who I may have harmed. That is the beauty of restorative conversations—and the most important part of doing it well, in a way that is anti-oppressive—they can be used with everyone, adults included. What are restorative conversations? Once a class/school community is built (and it has to be built first), restorative conversations enable us to repair the harm done to a member of the community. They are opportunities to unpack each student’s understanding of what happened, how they felt, and their suggestions for repairing the harm. The origins of restorative conversations come from Indigenous nations in what is currently known as the “Americas” and the South Pacific. What are the benefits of using restorative practices in schools? The restorative approach center on the dignity and humanity of each participant. It promotes listening and empathy followed by accountability and action. Research has demonstrated restorative conversations contribute to improved attendance and aspects of school climate such as safety and connectedness. They also advance racial, gender, disability, and economic equity, as exclusionary discipline rates (e.g., suspensions that take students out of their classes), are significantly reduced among Black, low-income, female, and special needs students when restorative practices are employed (West Ed, 2019). How are restorative conversations facilitated? Participants include the facilitator, the person(s) who caused harm, the person(s) who experienced harm, and each person involved can choose to invite an adult or young person to attend for moral support. The facilitator (an adult or a student that has been trained in restorative conversation facilitation) will ask a series of questions, one at a time. Each participant in the conversation will have an uninterrupted opportunity to respond to each question, speaking from the “I”. I use a talking piece to remind participants not to speak when someone else is speaking. (An adaptation for virtual conversations could be to stay muted until it is your turn to talk.) The following questions form a basic outline of a restorative conversation:

Several resources exist for educators to see more nuanced lists of questions to ask in restorative conversations. (For example, see this Teaching Tolerance resource or these Restorative Resources cards.) A final note for this section: Schools have different rules about the types of harm that should be addressed with restorative practices. Most schools specify that incidents involving violence are not handled with restorative conversations. Instead, students may engage in a re-entry circle or restorative conversation upon re-entering the community. Why is it important to identify feelings and unmet needs through restorative practices? This, to me, is the heart of the practice. The opportunity to listen to someone else describe how they were feeling in the moment or what need they had that wasn’t able to be met humanizes the person(s) who caused harm and enables that person to experience empathy for the person(s) they harmed. Even as a facilitator, many of these conversations have resulted in a much deeper understanding of my students’ experiences and a recognition of what I might be able to do to meet students’ needs or to support students to identify and address intense emotions in a healthy way. These conversations also helped me and my students in our immediate responses to disruptive or harmful actions. The more we practiced listening and identifying unmet needs in ourselves and others, we were more likely to respond to disruptive behavior with questions like “What do you need?” rather than reprimands. Practicing with Students It does not require students to harm or be harmed to engage in restorative conversations. Talking about unmet needs can be a lesson on its own. Every person can identify a time in their lives when they had an unmet need, so asking students to think about their own experiences and name the unmet need can be a powerful way to practice. For activities in which students are thinking about their own stories, you could invite them to share with a partner if they wanted or write to themselves or just think about it without putting it into words. I also have used book characters or historical actors or sample SEL stories to invite students to identify the character’s unmet needs. There are also a variety of sample lessons out there like this one from Teaching Tolerance that can help introduce the idea of restorative conferences to students. What if students struggle to identify unmet needs & restorative approach tumbles? As an adult, I still struggle with identifying what my underlying unmet needs are when I have an intense emotional response to a situation. Of course, students will likely struggle with this. I have adapted Glasser’s 5 unmet needs (survival, belonging, power, freedom, and fun) into an acrostic that helps me remember what the most basic unmet needs could be. I have been calling them BASE needs: Belonging, Autonomy (encompassing power and freedom), Survival, and Enjoyment. I made a poster for educators to remind ourselves and share with the class to help students identify (and ask about) others’ unmet needs when (or even before) disruptive behavior occurs. This mindset shift towards identifying unmet needs and hearing from students what emotions they were/are feeling refocused my attention from assigning a consequence of tackling the root cause of the problem. This also helped me as an individual bring more self-awareness to my emotions and unmet needs and improved my relationships with students, colleagues, friends, and family. As we pay increasing attention to all of our social and emotional needs this school year, let’s remind ourselves of the power of asking: “What does this person need?” These are what restorative practices are in their essence. In the past two weeks, I have read Layla Saad’s White Supremacy and Me and Tim Ferriss’s The Four-Hour Workweek. These are very different books, but they both ask readers to dig into deeply held beliefs and uproot them to make a powerful shift. As I think about the lasting impact of these books and what about each one has caused me to make real change, it is these two components: identifying and unlearning long-held beliefs and taking three next steps.

In White Supremacy and Me, Layla Saad has readers end the book by writing “three concrete, out-of-your-comfort-zone actions” you will take in the next two weeks. In The Four-Hour Workweek, Tim Ferriss has readers identify four life-changing dreams they have, and then tells readers to take three next steps over the next three days for each of the four dreams. He notes that each step should take a maximum of 5 minutes. I am constantly dreaming of what is possible, envisioning how things could be better. But I do not like just existing in a dream world. I then try to break these bold ideas down into concrete steps to make big changes and make what initially felt impossible, possible. Sometimes, that can come off as “This is easy to do!” which is far from the truth. My brain just goes directly to action. In a year when COVID-19 has caused a major upheaval in the lives of educators, I tend to skip right over the fact that this is incredibly difficult work to be forced to adapt instruction and while navigating the uncertainty and anxiety of ourselves, our students and families, and our colleagues. Additionally, in doing antiracism work, it is important to sit with new understanding and seek to learn more about the complexity of the problems—not rush to action. So many of us (definitely including myself here) want to rush to action before taking the time to fully understand the complexities of what’s going on and how our response could be unintentionally harmful, possibly by just paying lip service to racial justice without enacting any real change. That said, once we have a deeper understanding of a problem or can concretely define who we want to be or how we want to show up for our students, we will need to take action. That is when I can lean into my strength of breaking down a big goal into actionable steps to make big changes. I achieved my goal of running a marathon without stopping (after two attempts that required some walking), and I completed my Ph.D. program in three years while working full time. I did this through sheer force of will and some very specific calendars and timelines. I have also had dreams that have remained in dream form for years. For example, becoming multilingual has always been a goal. Why haven't I been successful? My goal wasn’t specific and I didn’t make a plan. Because I never made a clear plan, I never really got started. I often end my professional development workshops by encouraging participants to write down one next step they will take after the workshop. But, what I’ve learned from Saad and Ferriss (and my momentum towards the goals I set for myself after reading their books) is that taking one next step is not enough. There are more aspects to this “next step” thing that I did not realize missing from my workshop closing. Set a Deadline. Saad’s deadline was two weeks. Ferriss’s deadline was three days. I have found one week to be a helpful time frame for me to complete three steps. This has provided enough flexibility to work around the busy-ness of life and work, but also a close enough deadline that I’m less likely to forget. Whatever you choose as your deadline, make sure it is soon enough that you won’t put it off until “tomorrow,” which in my experience quickly becomes much later. Build Momentum. The difference between one next step and three next steps to make big shifts? Momentum. I can energetically dive into a new goal on Day 1, but after that, it’s easier to fizzle out. If we commit to three steps, one after the other, we build momentum, we start to make real progress towards our goals. That momentum is critical for working towards real change. Make The Actions Doable. Tim Ferriss says each of the first three steps should take no more than five minutes. In another book, Atomic Habits, James Clear recommends each habit takes two minutes or less. For example, if my desired habit is to practice on Duolingo every day, I can complete a lesson in two minutes and still continue my daily streak of practice. For these first few steps, aim for actions that will take 2 to 5 minutes. Write out your plan. I used to write down two big things I wanted to accomplish each day and focus on completing those tasks. Now, it feels more powerful to tie each of those tasks to a larger goal. So, I now frame each day’s task as: Which life-changing goal(s) am I working towards today? That fills my day with far more purpose than two random “check-the-box” tasks. Connect these steps to your identity. Layla Saad talks about being a “good ancestor.” Antiracism work requires us to unearth and discard white supremacist beliefs we have (often unknowingly) held. Rooting them out is difficult, emotional work, and what enables us to do that work—even when it’s hard—is to tie our identities to being antiracist or being a “good ancestor.” Atomic Habits author, James Clear talks about linking our habits to our identities as a way to ensure we follow through on our goals. He talks about conducting a yearly “Integrity Report” in which he asks: What are the core values that drive my life and work? How am I living and working with integrity right now? How can I set a higher standard in the future? He says this work helps “revisit my desired identity and consider how my habits are helping me become the type of person I wish to be.” We are more likely to continuously take action towards a goal if we see this work as critical to living out our desired identity, our best self. In the last two weeks, I’ve facilitated several virtual workshops on culturally responsive teaching and systemic racism. These particular workshops were focused on increasing awareness of racial injustice and learning how to first identify the problems. This is an essential first step, developing our understanding of the complex ways racism has been embedded into the fabric of institutions like school. However, many of us want to know what to do. Dr. Cherie Bridges Patrick has taught me that you first need to sit with it and truly seek to understand the complexity of the problems before jumping right to action. So, recognizing we need to do that first, I’ll do my best to answer what is becoming the most common question asked of me during racial justice workshops: “Once I have an understanding of the problem, what can I do about it?” Before diving into action steps, let’s look at a framework that may help us understand the variety of ways racism can play out in educational spaces. This framework is called the Four I’s of Oppression. (Described in detail here.) Here’s a brief summary:

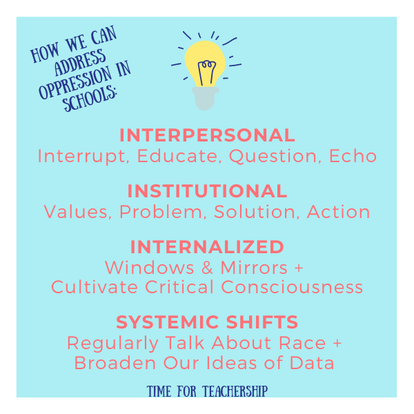

When we understand the different forms oppression can take and we recognize they are all interconnected, we are better able to form a plan for action. In the Moment Since ideological oppression is the idea that emerges through the other three I’s, I will focus here on what we might do when we see these other I’s in our schools. Addressing interpersonal oppression. Teaching Tolerance has a “Speak Up” pocket guide (linked here) that suggests four actions you can take when you witness someone do or say something racist. The four actions are: Interrupt (say something like “That phrase is hurtful”); Question (ask “Why do you say that?” or “What do you mean?”); Educate (explain why it’s harmful); and Echo (if someone else speaks up first, back them up with a simple “Thank you for speaking up. I agree that’s offensive.”) This pocket guide was actually designed to support students in speaking up, so you can use this with students as well! Addressing institutional oppression. Initiating policy change requires a multi-step approach. Although, some of the previous suggestions could serve as an initial step. For example, if you want to bring up a problematic policy, you might plan to say something at an upcoming meeting. You might pose a question like: Is the dress code helping all students learn? Then you can ask another teacher to be your echo so you are not positioned as the only person who sees this policy as a problem. When constructing your initial message, I like the approach developed by Opportunity Agenda, an organization that helps writers effectively communicate messages about social justice issues. They suggest this formula: Values, Problem, Solution, Action. Here’s what this might look like: “We’re all here because we want to help each of our students get the best educational experience possible. When students are removed from class due to dress code violations, they are losing instructional time. The latest data shows x number of students were removed from class last week for at least y minutes, and z number of students were sent home to change, missing hours of instructional time. To make sure our policies are maximizing student learning, I think we should start a committee to take a closer look at the dress code. This committee should include teachers, students, and families so that everyone who is affected by this policy has a voice in this process. It’s important to ensure our action reflects the inclusion and equity we want from the policy change. (For more on this, check out my previous post on shared leadership structures.) Addressing internalized privilege/oppression. Responding to internalized privilege and internalized oppression will require different approaches. For privileged students to recognize their privilege, you may want to introduce white privilege as a concept and highlight this is one way in which white supremacy manifests. Depending on the age of your students, the list in Peggy McIntosh’s article may be a helpful place to start. White students will also benefit from hearing stories and learning about the experiences of people of the global majority. Windows and Mirrors is a powerful approach with which to analyze your curriculum to ensure all students can have windows into stories of people who do not hold the same racial identity. This lens is also valuable for addressing internalized oppression, as Black, Brown, Indigenous, Asian, and AMEMSA (Arab, Middle Eastern, Muslim and South Asian) students need to see positive and complex representations of their racial groups in the curriculum. This Teaching Tolerance article also suggests explicitly debunking stereotypes and racialized myths, which cultivates students’ ability to be critically conscious of unjust representations of racial groups in textbooks or media. The article also distinguishes low self-esteem from internalized oppression, which is an incredibly important point. Whereas we may support a student with low self-esteem to see themselves in a more positive light, that’s not enough to address internalized oppression. We must help students recognize it for what it is: internalized oppression, stemming from ideas of white supremacy. We can help students identify how these stereotypes are perpetuated and who/what purpose these ideas serve. Systemic Shifts Acting in the moment is often what we think about when we wonder how we can respond to racism in schools. It’s certainly an important capacity to build. However, changing the broader school culture, shifting the system itself, can reduce the likelihood of racism moving forward. We don’t always want to be reacting. We want to find ways to be proactive. Make time for ongoing meetings about racial justice. One way to shift the culture is to make time for conversations about race with colleagues on a regular basis. As educators, we never have enough time to get everything done, so it may be challenging to see “adding” something else as doable. But racial justice isn’t something we’re adding to our plates. We are constantly “doing race” in our daily interactions. It’s embedded into everything else we do. If we can recognize this, we will see the importance of looking at our policies and data through the lens of its racialized impact. Through these conversations, schools can develop a culture of productive dialogue about issues of race and individual educators can build their capacities to see the complexity of racial injustice, including all of the identities that intersect with race to produce unique experiences of schooling for Black girls or queer Indigenous students, or Latinx students with dis/abilities, or transgender white students. Broaden the school’s conception of data. When we think of data, as educators, we often think of standardized test scores. Perhaps report card grades. Possibly graduation rates. Rarely do we move beyond this to consider other sources of data. Individual teachers may collect qualitative data from students and families throughout the year, but this is not usually systematized. We don’t usually look at qualitative data on a school-wide basis. Broadening our ideas of what types of data are valuable requires us to be clear on what we value as a school. Looking at standardized test scores, report card grades, and graduation rates reflects the importance we place on educational outcomes. Might we also want to look at how students and families experience schooling? Could we collect survey data and hold interviews or focus groups with students and families around questions of the degree to which they feel they belong in school or their voice matters? Asking what data matters and who we should gather data from can generate powerful shifts in thinking about how schools measure “success.” Inspired by Teaching Tolerance’s "Speak Up" pocket guide, I’ve made a pocket guide for this blog post to share with colleagues or keep as a handy reminder of the types of oppression and actions to take to address them. As we all grow and learn from one another, I invite you to share your ideas and experiences of identifying and dismantling racism in your schools. Since March, I have written many blog posts on distance learning. I thought curating these previous posts and bringing them together in one space may be helpful as we enter and continue to figure out the new school year together. I’ve linked each post related to distance learning below and provided a short summary to give you a sense of what the post is about. This year is asking a lot of educators. It is incredibly hard, complex work. It is my hope these posts can offer some support as you structure your distance learning tasks and supports for students and colleagues. Explore away! Transitioning to Virtual Learning: Questions to Consider This post is framed by questions to consider for each of the 4 R’s: “Room” setup, Rituals, Relevance, and Relationships. Transitioning to Virtual Learning: Tech Tool Suggestions While most of us know how we will deliver content this year, the second section of this post—assessing student understanding synchronously and asynchronously could be helpful. I particularly like the Two-In-One tools that enable you to share content and assess for learning simultaneously. This post includes a freebie describing 5 of my favorite tech tools and how I use them. Update regarding Google Meet: Breakout rooms are coming in October! Supporting Students with IEPs in the Virtual Learning Space Organized by Tomlinson’s 4 ways to differentiate, this post gives examples for differentiating content, process, product, and affect/environment. There’s also a choice board template freebie in this post. Supporting Students’ Mental Health During the Coronavirus Outbreak This post addresses topics like addressing racism and xenophobia, integrating COVID-19 into your lessons, sharing mental health tips with students, and additional resources to share with students (e.g., support hotlines). How to Be Well when Teaching from Home Following a rundown of the 6 dimensions of wellness from the National Wellness Institute, I share specific examples from my practice and a well-being tracker freebie. A version of this post was picked up and published by the National Wellness Institute in their International Journal of Community Well-Being. Digital Instructional Resources For Self-Paced Learning I share concrete examples of how you can use instructional resources to support students’ self-paced learning. The freebie for this post is a list of online sites and programs (nearly all of which are free), organized by subject. Opportunity: Rethink Assessment & Grades This post is the first in a mini “opportunity” series—posts that introduce the mindset shifts that can help us see beyond the challenges of the situation we have been thrust into (teaching remotely) to envision opportunities for new ways of teaching and learning. This post specifically focuses on how assessment and grades might look different in a distance learning environment. Opportunity: Genius Hour Genius Hour is one way to promote student engagement during distance learning. In this post, I share the 3 big lessons I learned when doing Genius Hour in my class. The freebie is the student planning doc I used to jumpstart a semester of Genius Hour. Opportunity: What I Need (WIN) Time Many teachers offer small group support or 1:1 meetings for students during distance learning. Just like in a physical class, you may wonder what the rest of the class is doing during this time. This post walks teachers through the basics of WIN Time to help students identify what they need to work on and ensure they have access to the tools they need to work on it. Opportunity: Student Goal Setting Asking students to set personal goals during distance learning is brilliant. This post talks about how you can make the goal setting process truly impactful. There’s also a SMART goal template freebie. Opportunity: Personalized Pathways (Part 1) Personalizing instruction or differentiating instruction have always been big in the education world. The need for personalized instruction has grown even more during distance learning. Pathways are one strategy educators can use to personalize instruction. This post provides an overview of pathways (i.e., what, why, and how). Opportunity: Personalized Pathways (Part 2) This post covers the logistics of how to literally set up a pathway, including what tech tools to use and how a pathway differs from a playlist. There’s also a pathway tracker template freebie to get you started. Live Classes or Asynchronous Tasks: Benefits of Each This post summarizes the benefits of synchronous vs. asynchronous activities with the goal of helping teachers think about which activities can be done live and which can be completed during non-class time. Live Classes or Asynchronous Tasks: The Best of Both Sometimes you don’t need to sacrifice the benefits of one form of instruction when you choose the other. This post covers how you can use particular tools (many asynchronous) and still maintain many of the benefits of the other type of instruction (often synchronous). The freebie for this post is a set of student-facing weekly plan templates to help you and your students organize what they will do each day or week Live Meetings or Asynchronous Tasks: Leader Edition The leader version of the synchronous vs. asynchronous post series, this post helps leaders think about when to hold live meetings with staff and what can be done asynchronously. It wraps up with a few final tips and a podcast recommendation. Scheduling Your Work Week While Working From Home This post contains what is perhaps the most popular freebie I’ve ever created. The post itself lists 5 tips for structuring your work-from-home life. The freebie is a scheduling template set up to reflect the tips listed in the post. Within the freebie, you will also find a sample schedule to help you get started. In case you missed one of these posts the first time around, I hope this collection provides you with some inspiration to support your students during this unique school year. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed