|

I learned a lot from listening to my students. Recently, I looked back at some of the feedback I got from students when I taught 10th and 11th grade literacy. Their responses are illuminating even years later. What did they say they liked?

What did they say should be improved?

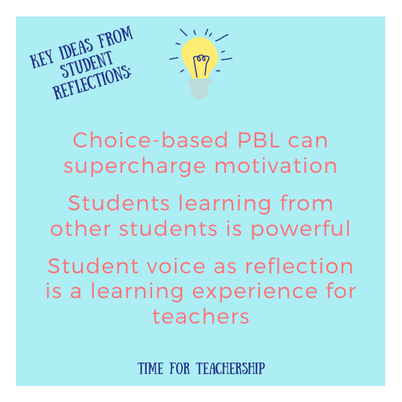

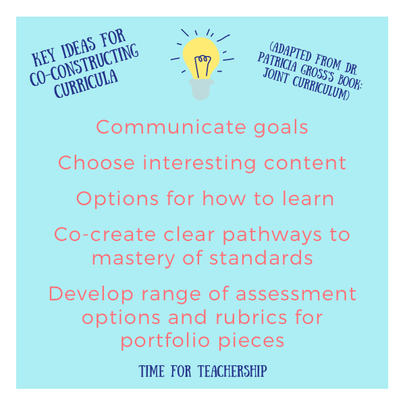

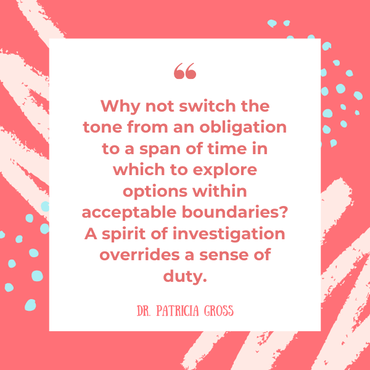

I am still blown away by the insightfulness of my former students. They wanted more choice, more opportunity to share their ideas with the world and make a meaningful, positive impact on relevant social issues. The last point on the feedback list emphasizes students’ eagerness to learn and grow as writers, but they were strategic in how to go about this. They advocated for less drafting and more of a focus on revision. Students are brilliant! I realize all students are not the same, and these reflections of my students from years ago may not perfectly align with what all other students prefer, but I’ll pull out some notable themes that may help us all as we design engaging units for our own students. Choice-based PBL can supercharge motivation. My students’ reflections and my observations of students in action support what the research says about the power PBL and student voice have to increase student engagement, motivation, independence, attendance (BIE research summary), positive-self regard, feelings of competence (Deci & Ryan, 2008), and academic achievement (Mitra, 2004). They were aware of this, and wanted to continue reaping these benefits, which was evident in their suggestions to have even more choice in the topics studied, books read, and demonstrations of mastery. Students learning from other students is powerful. Many students said that circle discussions were one of their favorite activities of the year. Several students explained that hearing from other students was the reason they became more open to other perspectives and were able to recognize oppression that they hadn’t seen before. Being open to hearing other perspectives and recognizing oppression was one of my primary goals for students—a clear and relevant application of the critical thinking and analytical standards so many of us are tasked with teaching. Students’ comments made me increasingly aware that the time students have to share their ideas with one another and the space we make for students to truly be listened to, is critically important. When I plan my units and individual lessons within those units, I try to keep this in mind. As a result, at least half of my lessons are dedicated to student work or student talk time, to enable students to have these meaningful learning experiences. Student voice as reflection is a learning experience for teachers. One of the things student voice researchers advise is that when we ask for students’ opinions, we do something with the feedback. This doesn’t mean we always implement every idea a student shares, but we want to sit with it, think about it, and respond to each of the pieces of feedback with what we’re doing to move forward with it or why it’s not able to happen in this moment or in the exact way a student suggested. (For reference, I followed up on the above student feedback, the following year by trying out at semester-long Genius Hour in which students had full control of designing their own units—we had 60+ topics going and nearly as many different ways of demonstrating mastery. While it did not go perfectly, my returning students were able to see my commitment to listening to their ideas.) Dana Mitra (2006) depicts three levels of student voice as a pyramid. At the bottom level, students are simply being heard, perhaps by sharing their opinions on a survey—this is the most common type of student voice and also the lowest level. At the middle level, students work alongside adults in partnership to accomplish school goals. At the top level is building capacity for student leadership—less common than the others and the highest level of voice. While a reflection activity on its own seems like it would fit on the bottom level of Mitra’s pyramid, enabling students to recommend or even make these adjustments themselves during the unit or prior to the unit, would have brought us up to at least the middle level of the pyramid. Engaging in my own reflection on teaching, I would like to create more opportunities for students to be in the top two levels of the pyramid, so students (either independently or by collaborating with me) could make the necessary course corrections the moment it’s needed. Students are engaged when they have choice and voice in what they learn about and how they demonstrate learning as well as the opportunities they have to learn from one another. Designing curricula that enables students to choose their own pathways of learning content and building skills, amplifies student engagement and enables students to flourish. Adopting project-based learning, enabling meaningful opportunities for reflection and critical feedback, and making space for students to learn from each other are just three ways we can do this. What other ways do you amplify student voice in your classes? What else have you learned from listening to students?

0 Comments

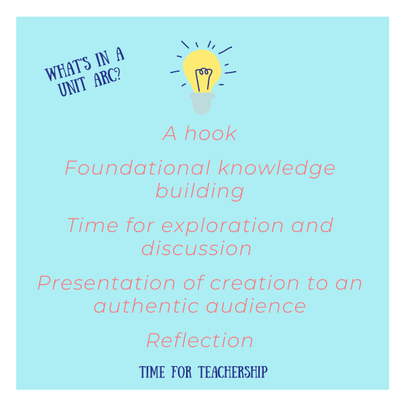

I still remember sitting across from my curriculum coach, Janice, during my third year of teaching. When she shared the concept of a unit arc, I could barely believe it. I was awestruck, while at the same time, thinking, “Really? I can do that?” With the introduction of this one concept, my entire idea of what was possible with regards to curriculum design drastically changed. All of a sudden, I saw a path forward that involved creating amazing, topical units without spending 20 hours every weekend to finish them. So, what is a unit arc? I define a unit arc as: The pattern of purposeful learning experiences in which students engage throughout a unit. As with any unit, we pack it with learning experiences for our students, but the key difference with a unit arc is the intentional pattern it follows. This pattern becomes predictable to you and your students because you reuse it from unit to unit. Once I had a unit arc, I no longer spent hours determining which activity to prepare for each lesson, because I used the same arc and same templates for these activities. From then on, my prep time was focused solely on collecting and organizing the content material. What might an example of a unit arc look like? Different subjects may gravitate towards different kinds of unit arcs. In Science, the 5 E’s may frame the unit arc. The unit arc I adapted from my coach was originally intended for Social Studies content, but with small adaptations (e.g., bullet point 4), it can work for many subject areas. I’ll share it here:

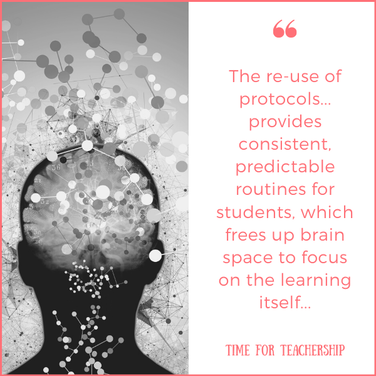

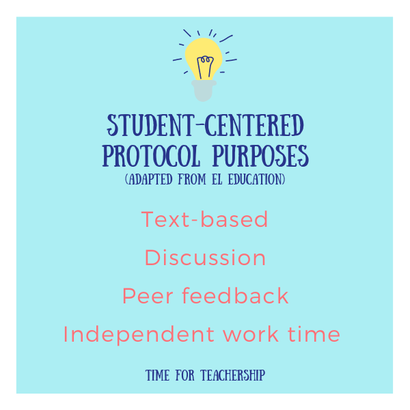

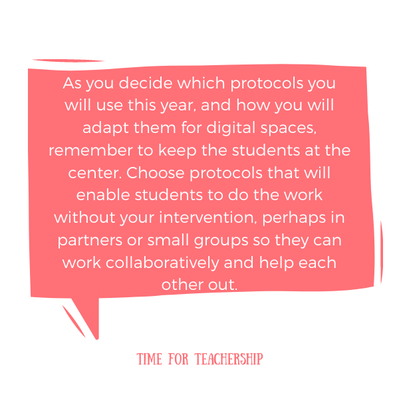

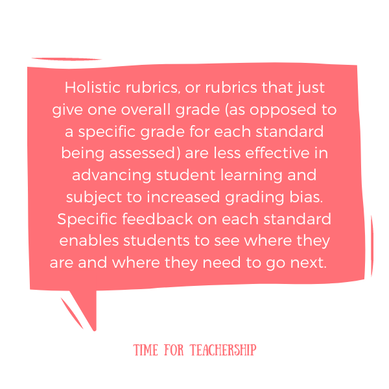

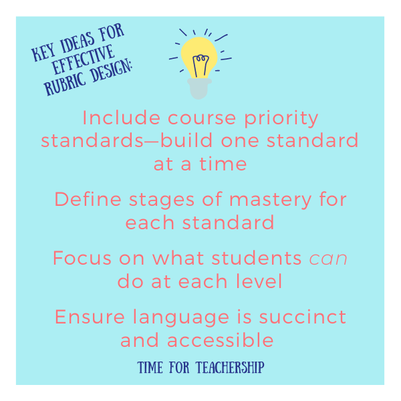

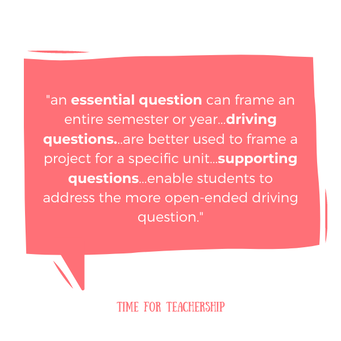

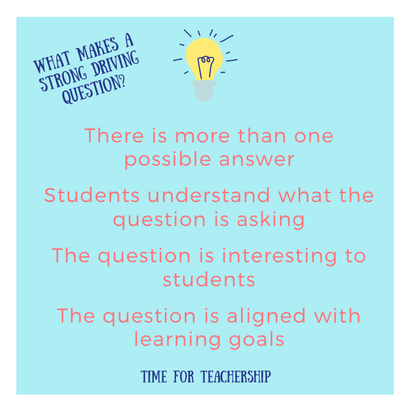

You’ll notice there is an arc of engagement here. First, interest needs to be sparked, so we’ll start with a whole lesson dedicated to a hook. This might be a current event or a documentary that connects key concepts we’ll cover in the unit with a modern issue or event. Then, building on students’ existing knowledge, we lay the foundational knowledge with an overview of key concepts and important primary sources. From there, students are given space for exploration, discussion, further research, and as they work, students apply the learning in novel ways and creativity to produce original work. The units culminate in a presentation of some kind. I think it’s important, whenever possible, to provide opportunities for students to present or share with an authentic audience, beyond the teacher. Following student presentations of their creations, we reflect on what went well, what students found helpful or unhelpful (e.g., project strategies, types of teacher or peer support, specific protocols), and what could be improved next time. Taking the time to reflect was critically helpful to me because I was able to learn so much from what students had to say about the ways I could better support them in their work. Don’t students get bored of the same activities over and over again? I get this question a lot, and surprisingly, students were rarely bored by repeated protocols. In fact, many of my students said they liked the predictability of knowing what was coming next. I found the content, more than the process, was what made the activity engaging, and that changed each day. That said, certainly, all students are unique, and you know your students best, so do what feels best for your class. In my class, the one protocol that students sometimes grew tired with was circles, simply by nature of how many times they engaged in it. I used circles more frequently than any other protocol in my unit arc. We had weekly circles in my class, and students regularly had circles in their other classes, as it was a practice used by several teachers in our grade team, so students often engaged with this protocol several times a week. Despite being tired of the protocol, an engaging topic of discussion in circles would usually be enough to re-engage students after the initial “Another circle?” comment a student would occasionally make when they saw the setup of the room. Ready to get started planning with unit arcs? If you don’t already have it, grab my free backwards planning template to get started building your next unit. Go to File > Make a Copy to be able to edit the unit arc to one that fits your content area, your grade, and your teaching style. Once you’ve made your own unit arc, you can share your creation in the comments section or in our Time for Teachership Facebook group! In my review of the literature on student voice, I have attempted to catalogue what I call “mechanisms” that amplify student voice in educational spaces. One of the mechanisms I have identified is “pedagogy,” a very broad mechanism that encompasses several key practices, including: scaffolding, discussions of social injustice relevant to students, flexible space (i.e., co-creating learning spaces with students), and co-constructing curricula with students. It is the latter practice, rare but powerful, that this post will address. The notion of co-constructing curricula sounds intimidating at first, but I think it’s much more accessible and actionable when we think of it as a continuum. Teachers who have been co-constructing curricula with students for a while are going to have much more fluid and flexible planning practices than teachers who are trying it out for the first time, and that is completely okay. I want to spend some time talking about what co-constructing curricula is and what that could look like in your classes. To help frame this post, I use the work of Dr. Patricia Gross. Specifically, I share insights from her book, Joint Curriculum, which details the stories of two teachers who enlisted her help in shifting their teaching and planning processes to co-construct curricula with their students. Gross describes what is involved in joint curriculum design as follows: “(a) Students and teachers who communicate goals, envision and strive toward common aims; (b) they mutually interrogate what content choices stimulate inquiry through individual and group interests; (c) they negotiate methods of how to proceed to accommodate individual needs and learning styles; (d) they collaborate to sequence when sufficient exploration and practice lead to comprehension; and (e) they devise assessment criteria to specify why to inquire into topics and determine expected outcomes” (1997, p. 5) [emphasis in original]. In Gross’s bolded words we see some key ideas of co-constructing curricula. It involves communicating with students about the goals of the class (and recognizing that each student’s goals may be slightly different). It involves figuring out what specific content is interesting and relevant to students (again, noting that interest level will not be identical for all students). It involves a conversation and perhaps a provision of options to students about the class protocols, “text” choices, and perhaps tech tools that are available for students to engage in learning course content and skills. It involves a co-construction of a clear path to mastery of a particular skill or content understanding with the flexibility for learners to move at the fastest pace that they are able to move without disrupting comprehension. It involves a degree of co-construction of a project-based, perhaps course-long, rubric (e.g., the course priority standards and what success looks like at each level of mastery). This assessment piece also involves providing a range of assessment options, so that students’ grades are reflective of a portfolio of work, the pieces of which they should be able to revise and resubmit. One place along the continuum of co-constructing curricula with students is the use of Genius Hour, also known as 20% Time. This strategy gives students 20% of class time (maybe one day a week or one hour a day) to work on projects of their own design. I was fascinated with this concept in my last year of teaching, to the point in which I tried doing a Genius Hour semester, all day, every day! After testing it out, I would not recommend such extreme fluidity for such a long duration. However, during the first 2 months, students were incredibly energized by their work! For example, projects that were created in that semester included: student-designed t-shirts to raise awareness of problems facing the LGBTQ community and incarcerated mothers; a video game a student created after learning a new coding language; 30-minute documentaries including one on the hypocrisy of the founding fathers and one on the importance of music; a student-designed field trip series, in which a student filmed visits to social justice art installations around the city; and a comparative essay written after reading two novels (this student wanted more practice before completing this task for their senior portfolio the following year). If you’re interested in starting Genius Hour with your students, I’ll re-share a template I used for the first few days my students engaged with this project. Just click the button below to access it! (Also, if you missed my masterclass this week, sign up for a spot next week, where I’ll be sharing how you can get my entire Google Drive folder of Genius Hour resources.) Of course, you don’t need to start Genius Hour to co-construct curricula with your students, you can simply ask for their thoughts more often (and then use that information to adjust your planning.) I love Gross’s point that, “Joint curriculum design values teacher expertise. However, teachers impart information sparingly to pique students to verify or question information to draw and substantiate their own conclusions” (p. 29). So, we can create a unit, and begin implementation, but leave some space (perhaps in the form of choice boards to explore content subtopics or open-ended projects options) for students to run with whatever piqued their interest. At first, my students were wary about co-constructing curricula. I was met with initial resistance (by some students, not all) in the form of “Just tell me what to do, Miss.” This saddened me, but when students have experienced education as being told what to do and having little voice in that process for so long, it makes sense to me why that was their initial reaction. For these students—there were several in each class—we formed a small group to brainstorm ideas together. After asking what interested them and getting no responses, I threw out some possible options for discussion, and they chose one and adapted it as they went. I will say those students were less enthusiastic about their projects than the other students, and this realization reinforces my conviction that student voice in the co-creation of learning experiences is critically important at all ages of learning. Students enter school as 4 or 5 year olds, curious about everything! If we consistently teach without consulting and co-creating with students, that curiosity fades more and more each year. Gross points out that students are mandated to be in your class, but she poses this question for thought: “Why not switch the tone from an obligation to a span of time in which to explore options within acceptable boundaries? A spirit of investigation overrides a sense of duty” (p. 59) [emphasis in original]. I love this concept of exploring options within acceptable boundaries. While it may be intimidating, remember it’s a continuum. Determine what degree of co-construction you’re ready to test out, and plan with choice and flexibility in mind. Given the decreased levels of engagement many teachers have seen during distance learning this past school year, I think this approach is definitely worth a shot. Protocols, also called activities, procedures, or learning routines, are the structured ways in which students engage in learning. For more background on protocols, check out this previous blog post. I specifically advocate for student-centered protocols, which ask students to grapple with the work and require very little, if any, direct teacher involvement. Of course, teachers can always support students as needed during protocols, but students benefit from the grappling when they are engaging in an activity within their zone of proximal development (e.g., they are able to accomplish the task with some peer support or scaffolded questions built into a protocol). For example, a well-built SMART Goal Template makes it possible for students to independently set and track thoughtful goals far more effectively than simply asking students to set a goal and track their progress without the scaffolding built into the protocol material. How many protocols should I use? One of the key ideas for making planning and teaching manageable for teachers and students is identifying a few high-leverage protocols that serve a handful of different purposes, and re-using them again and again. The re-use of protocols enables you to spend less time making new materials or teaching new directions for class activities. It also provides consistent, predictable routines for students, which frees up brain space to focus on the learning itself because they’re not wasting energy learning a new protocol. In science speak, it reduces the cognitive load. I like EL Education’s recommendation of having three to five go-to protocols that span a few different purposes. This is just enough for about one protocol per key purpose. Of course, you can always rotate in a new protocol to mix things up, but “mixing it up” too often can lead to student confusion and shut down. What may seem very repetitive to us as teachers can be reassuring and engaging for students. What are the different “purposes” protocols serve? EL Education shares the following protocol purposes on their site: text-based, discussion, peer feedback, decision-making, and presenting. When I think about these purposes in terms of how I used them in my class and how I’ve supported teachers in using protocols in their classes, I would adapt this list slightly to focus on the first three (text-based, discussion, and peer feedback) and I would add independent work time as another protocol purpose. The EL curriculum includes one hour daily of what is effectively a differentiated station rotation, but most teachers don’t have that time baked into their schedule, and thus would need to fit that into regular class time. If you can identify one go-to protocol for each of these—four total protocols—I think that’s all you really need. Your content or your teaching style may make you gravitate to one of these purposes more frequently than the others, and that’s okay! You can have multiple protocols for your most-used purpose. For example, in my high school class, I had two core discussion protocols, but used them in different ways and at different rates. I used circle protocol weekly, mostly for current events discussions and community building. I used the more content-focused Socratic Seminar, which enabled students to practice collecting and analyzing evidence to form and present academic arguments, about once a unit. Can protocols be used during distance learning? Absolutely! Student-centered protocols are great for distance learning, as they promote student independence and if well-designed, do not require direct teacher intervention. You may want to use different protocols for distance learning than you would in a physical classroom, but you can also adapt an in-person protocol for online use. For example, a gallery walk is a great text-based protocol. Instead of physically walking around a room and writing on chart paper, you might instead have students use a Padlet, with each column representing one “chart paper” or station. Alternatively, you could set up a Google Slide presentation for students to add digital post-its to a “digital chart paper” (i.e., a slide). EL Education suggests a virtual protocol called “Pass the Mic” for share outs in virtual class meetings, which essentially asks students to volunteer to share with the class by umuting, sharing for no more than 60 seconds, and then saying “I’m passing the mic to _____.” That student then unmutes and continues the process. This just simplifies the structure of the share out a bit, and can be used with many other protocols that have a whole class share out component. EL’s sample virtual learning norms are also worth a look as we think about how to build a virtual class culture for student engagement and discussion. (The norms are linked on this page.) As you decide which protocols you will use this year, and how you will adapt them for digital spaces, remember to keep the students at the center. Choose protocols that will enable students to do the work without your intervention, perhaps in partners or small groups so they can work collaboratively and help each other out. (To do this in a virtual space, you could use breakout rooms during a whole class meeting, or you could set up meetings with small groups of students in exchange for fewer whole class meetings each week). Finally, centering students in the learning process also means asking students to weigh in on what is working for them and what is not. Typically, I’ll ask for feedback on a protocol once I know students understand and can do the steps of the protocol, so that I know the feedback I’m getting is really about the learning potential of the protocol and not the students’ unfamiliarity with the protocol steps. Sharing your go-to protocols with other teachers on our Time for Teachership Facebook group or in the comments below is always welcome. This way, other teachers draw inspiration from you, and you can get inspiration from others! As we continue our journey into justice-oriented unit design, we’re moving from how we spark engagement with a driving question to how we assess student mastery and offer standard-specific feedback. This post will address questions including: What kind of rubric should I use? How do I determine which standards will be assessed in this project? Do you have tips for using effective language in my rubric? What steps should I take to start building my rubric? Let’s take these questions one-by-one. What kind of rubric should I use? To do this well, we need a standards-based rubric. Holistic rubrics, or rubrics that just give one overall grade (as opposed to a specific grade for each standard being assessed) are less effective in advancing student learning and subject to increased grading bias. Specific feedback on each standard enables students to see where they are and where they need to go next. Ideally, the rubric should also be mastery-based, meaning it defines what different levels of mastery look like within each column of the rubric. Research found mastery-based grading resulted in a 34% increase in student achievement compared to traditional grading (Haystead & Marzano, 2009). Mastery-based rubric categories might include: approaching the standard, meets the standard, and above the standard. Alternatively, a single-point rubric could be used, which would list the standard in the center column, and have blank columns on either side (one for below or approaching the standard and one for above the standard) for students and teachers to write in their own language so they can specifically address the evidence of the students’ degree of mastery for each standard. If you’re interested in a mastery-based rubric template, I’ll re-share my free rubric templates below. How do I determine which standards will be assessed in this project? The rubric should be the result of backwards planning. (For more on backwards planning, see this post and this post.) This means you’ll want to identify the priority (i.e., most important) standards the project will assess. Your rubric should be given to students at the start of a project or unit so they know what they will be assessed on from the start. When choosing your priority standards, try to choose higher-order standards (e.g., DoK 3 and DoK 4). Do you have tips for using effective language in my rubric? Effective rubrics use language that focus on what students can do, rather than what they can’t do. This is particularly difficult in the below or approaching phase of mastery. I still struggle with this piece myself, but I’ve found it helpful to think about the supporting standards (e.g., DoK 1 and DoK 2) that are stepping stones students need to master before they are able to master the higher-order priority standard, and I try to use language that reflects evidence of these “stepping stone” standards. Language should also be clear and accessible to students. Rubric language should include all of the details required to make it clear to students what is being asked, but should include no more language than is absolutely necessary. To keep the document accessible to students, a rubric should be as short as possible. Finally, the language used across different levels of mastery (i.e., in each column) should be similar. This parallel language will make the rubric more coherent. What steps should I take to start building my rubric? Building a rubric is a lot of work. (Tip: I actually build one rubric for the whole year with all of my priority standards, and then delete standards if they are not to be assessed in a particular unit. This saves me a lot of time and provides students with consistent expectations.) Before doing anything else, choose which kind of rubric you will use (see earlier section on this question). Once you have chosen a rubric style, I would start with one priority standard. Read the standard as written, and then define what mastery looks like using similar language. This will be your meets standards category (or the middle category in a single-point rubric). Before you continue, review the language for clarity and student accessibility. Revise as needed. Once your meets standard column is all set, adapt the language for the mastery level above and below. Once the entire row of your first standard looks good, move on to the next standard. Creating a coherent, standards-based rubric is a necessary component of backwards planning, and it is critical to equitable grading. If you have additional rubric design tips, please share in the comments below or in our Time for Teachership Facebook group. This past week, I wrote about the importance of student engagement and teaching for racial and gender justice as a powerful opportunity to engage students in academic learning. If you haven’t read those yet, I recommend starting there to better understand the context and the why behind the next several blog posts, which will focus on aspects of curriculum design. (You can read “Promote Student Engagement + Teach for Justice” here and “Why Teach for Justice?” here.) As I continue to discuss curriculum design, I will use a project-based learning approach. This is because research indicates project-based learning (PBL) enhances student engagement, student motivation to learn, student independence and attendance, content understanding and retention, and even test scores compared to traditional, non-project based, teaching (BIE Research summary). According to PBL Works, one of the “Gold Standard” elements of PBL is: a challenging problem or question. Let’s take a closer look at this element. Is a driving question the same as an essential question? Grant Wiggins, co-author of Understanding by Design, distinguishes between an essential question, a compelling (i.e., driving) question, and a supporting question in this blog post. He clarifies that an essential question “recurs over time” and “points toward important and transferable ideas,” while a driving question is rooted in specific content. Supporting questions “have agreed-upon answers” and “assist students in addressing their compelling questions.” All of these question types are valuable, but they all serve different purposes. By virtue of being broad, an essential question can frame an entire semester or year. Because driving questions are grounded in content and they require application of content understanding, they are better used to frame a project for a specific unit. Finally, supporting questions help us check for factual understanding and provide scaffolded support to enable students to address the more open-ended driving question. This synthesis of ideas from Grant Wiggins and Debbie Waggoner does a great job of clarifying these differences with examples (Bush, 2015). What makes a strong driving question? A strong driving question is key to the success of a project-based unit. If students are not excited to address the question, the project immediately becomes less effective. A high-quality driving question should meet the following criteria:

As you review or create a driving question for an upcoming unit, use these criteria as a checklist to make sure your driving question is strong. If it doesn’t meet these criteria, rewrite at least 5 iterations of the question, and pick the one that best aligns with the criteria. If none of your drafts check all of the criteria, keep drafting until you get there! Don’t be afraid to ask for feedback from teachers and students. Let’s look at an example. It can be difficult to write a strong driving question, so we’ll examine a concrete example. Let’s say I’m designing a unit for a Social Studies course entitled, Revolutions Through History. The unit is about the American Revolution. I draft the following three questions:

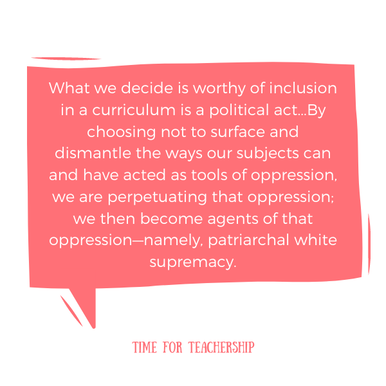

Looking at these three questions, I like the middle one best for a driving question. It’s grounded in specific historical content, it’s debatable, and it’s fairly straightforward, and students have to deeply understand the content to address the question with any nuance. The first question I drafted would make more sense as a thematic question for the year. For any unit, any revolution we talk about, during the year, we could always return to this question. We could even use the unit’s driving question to inform a response to this essential question. For example, if a student says it wasn’t revolutionary because it only grants specific rights to white, land-owning men, they could then say a necessary ingredient to a revolution is inclusion of all social groups in the revolution and subsequent policy creation. Finally, the third question is more of a scaffolding question. Let’s say all of my students say, of course it was revolutionary, it’s in the name: American Revolution. I might want to push their thinking by asking a factual question like this. Simply putting a question like this out there can help students come to see different perspectives and formulate new or more complex arguments. For more examples, John Larmer, editor of PBL Works and co-developer of the Gold Standard PBL model, has a great article on the difficulty of crafting an engaging driving question. In it, he shares several sample questions and talks about the two main types of questions: debatable questions and solution-generating questions. Lastly, if you’re interested in a worksheet to help you draft your driving questions, click the button below to get this week’s freebie. Happy question drafting! In her book Reading, Writing, and Rising Up, Linda Christensen begins the first page with, “Why reading, writing, and rising up? Because during my 24 years of teaching literacy skills in the classroom, I came to understand that reading and writing are ultimately political acts.” She goes on to write about how historically, enslaved people in the U.S. were denied opportunities to learn to read and write and in more recent history, government funds are spent on things like going to the moon rather than investing more resources in education while the racialized opportunity gap persists. Curriculum is Not Neutral I agree with Christensen. How and what we teach in literacy, history, math, science, art, physical education, technology...all courses...is inherently political. What we decide is worthy of inclusion in a curriculum is a political act. History and literacy are often cited as the subjects in which it’s easier to address issues of injustice, but unpacking how math and science are applied in practice is a powerful opportunity to examine how STEM concepts can and have contributed to racial and gender inequity, even today! Furthermore, we can introduce students to ways math and science (and literacy and history and art and PE) can be applied in ways that advance racial justice. By choosing not to surface and dismantle the ways our subjects can and have acted as tools of oppression, we are perpetuating that oppression; we then become agents of that oppression—namely, patriarchal white supremacy. Learning About Relevant Issues is Engaging Another reason to center issues that impact students’ lives in our curriculum is that it amplifies student engagement. Christensen writes, “I couldn’t ignore the toll the outside world was exacting on my students. Rather than pretending that I could close my door in the face of their mounting fears, I needed to use that information to reach them” (p. 4). Here’s the thing: all students want to learn. But, it’s hard to engage with a curriculum that is just not interesting. As educators, it’s tough to engage all of your students—some teachers have hundreds of students to engage! And to be perfectly clear, I did not and still do not engage 100% of my students every day, but once I started designing units around issues relevant to my students, the number of students I was able to engage was far higher than when I was teaching from a textbook. To ease the minds of teachers nervous about going off-book, Christensen writes, “I want to be clear: Bringing student issues into the room does not mean giving up teaching the core ideas and skills of the class; it means using the energy of their connections to drive us through the content” (p. 5). How does community building fit into this? When teachers ask what they can do to increase student engagement, I often share two key ideas: build a thriving classroom culture and design engaging curricula. Christensen notes both are necessary, pointing out that one informs the other. She says, “Building community means taking into account the needs of the members of that community. I can...play getting-to-know-each-other games until the cows come home, but if what I am teaching the class holds no interest for the students, I’m just holding them hostage until the bell rings” (p. 5). Building relationships is a critical piece of engagement because it enables us to be more effective educators. To Foster Justice-Oriented Student Leadership Something I often hear in education is the importance of educating “future leaders.” While I insist students can and should be leaders while they’re still in school, to be effective leaders, as youth or adults—students need to learn and practice leadership skills. And the type of leadership we support in students to practice is critical. As a leadership scholar, I can tell you there is far less scholarship on student leaders than on adult leaders. In my research, I suggest we specify the kind of leadership we’re trying to foster in students. Specifically, I posit student leadership should encompass critical awareness, inclusivity, and positivity. Let’s take a closer look at how I define that first one—critical awareness: “Preskill and Brookfield’s (2009) book on social justice leadership as well as the self-awareness and self-development tenants of authentic leadership (Walumbwa et al., 2008) contributed to this study’s definition of critical awareness as reflecting on, understanding, and questioning positive and negative attributes of one’s self and society to foster equity and growth.” (Lyons, Brasof, & Baron, 2020). By this definition, students with the capacity to be critically aware are focused on working towards equity and are able to critically reflect and question information and events as well as their own thoughts and actions, all in service of personal and societal growth towards racial and gender equity. This is what I hope for all of our students and leaders, but this capacity doesn’t just happen. It takes work to enable it to flourish. We can help students do that work. If you’re interested in teaching for justice but overwhelmed by the idea of building units from scratch, I have something for you. In just over a week, I’m offering a free 1-hour online masterclass where I’ll be sharing my biggest secrets on creating brand new units. Click the button below to save your seat in the masterclass. For approximately the next 30 days, I want to focus on how we create amazing units for our students this year. I think it’s every teacher’s dream to have 100% student engagement in their lessons, and I want to help you achieve that dream. Most educators saw a drop in student engagement this spring during distance learning. Of course, lack of access to devices and WiFi contributed to this, but getting our students online is just the beginning. We’ll also want to consider what kind of supports (e.g., emotional, relational, cultural), pedagogies, and curricula (e.g., content, assessments) will best support our students to be successful this year. As many educators are committing (or have renewed their commitment) to antiracist teaching, these educational pieces—supportive environment, pedagogy, curriculum—can be critically examined with antiracism in mind. Each teacher can ask: Does the class environment (building-based or online) we’ve built, the pedagogies I employ, and the curriculum I use foster racial equity? If the answer is no, we’re fostering racial inequity. Each of these pieces could get their own blog post series, but I’ll quickly address the first two and then address equitable curricula in more depth. Supportive Environment Creating racially equitable environments require an extra effort to help students and families of the global majority (a term I’m starting to use instead of “people of color”) feel a sense of belonging in school. Equity necessitates we offer more support to students who need more support. Equality is offering the same to everyone; equality maintains the status quo. We need equity, not equality. Pedagogy Zaretta Hammond talks about culturally responsive teaching as prioritizing the learning. Kids need to get into the learning pit and grapple. We need to have high expectations for students, and give grade level work even to struggling students because remediation does not work. Of course, we will need to support students with scaffolding as well, but they need exposure to grade level content or else the opportunity gap, which disproportionately hurts Black, Brown, and Indigenous children, will persist. To take stock of your equitable practices, I’m re-sharing the equitable practices inventory—a freebie from Fall 2019. Curriculum Choose to teach about injustice and activism. We have an incredible opportunity to build on our society’s increased attention towards racism in the U.S. and to bring that energy into our classes this fall. The last 4 years of my teaching career, I made the decision to teach all of the Literacy standards my class was supposed to cover through intersectional feminist content. We can build curriculum around social issues like racial and gender injustice, and we can support students to become civically engaged activists. We can do that, but not as an add-on. Doing it well requires an intentional choice to make this a priority. Co-construct unit ideas with students. Once I made a conscious choice to teach for racial and gender justice and built units around current events and issues relevant to my students’ lives, I saw significantly more student engagement. I learned to share ideas for units with my students and ask them for feedback or to tell me what they wanted to learn about. Create projects for an authentic audience. Another key piece to the increased student engagement I saw was having an authentic purpose for summative assessments beyond submitting work to me for a grade. This often meant my students presented their work to an audience beyond the class. Here are some examples of my students’ projects: a live poetry performance and a social justice expo that school staff and students were invited to watch; a product created for purchase, like t-shirts raising awareness of the mistreatment of pregnant women who are incarcerated; documentaries submitted to a national film competition; issue-based circle conversations facilitated with younger grades; a proposal presented to school leadership to change school policy. Knowing their project would be useful to an audience beyond just me and the members of their class was a strong motivator for students to learn as possible to make their project the best it could be. Grade social justice skills. I’ve written a lot about grading lately—I support a mastery-based grading system that provides students specific feedback on where they are in a progression towards mastery for each content standard. What we measure and grade communicates to students what we value, so I recommend incorporating social justice standards into the curricula we build. Teaching Tolerance has an excellent list that’s slightly adapted to fit each grade band. Find inspiration. Finally, if you’re thinking all this sounds great, but how do I get ideas for these amazing units I want to build? I often got my ideas from reading, watching the news, and listening to podcasts. The more I learned, the more I had questions to advance my own learning, and it was these questions that produced the seeds that eventually grew into units. Places where I consistently find sparks of inspiration include the podcasts: Codeswitch, Teaching Hard History, and Queer America. I also love publications like the blog from ReThinking Schools, particularly their posts tagged as curriculum. Also, the PBL Works Youtube Channel has a project videos playlist that’s great for seeing the possibilities of what amazing units could look like. You could also reach out to a local activist organization to help you co-construct a unit. Quick note: you can absolutely create justice-based curricula in any subject area. For example, ReThinking Schools has an entire book published about the intersection of social justice and math. Given the possibility of continued distance learning, this is a critical time for us to invest in student engagement, and we can do so in a way that prioritizes racial justice. We don’t have to choose between addressing COVID or racial justice. They are not mutually exclusive. As we create new curricula, let’s explicitly integrate racial justice work, activism, and civic engagement so our students are both engaged in our lessons and building the skills to be impactful leaders for justice in their lives. 7/2/2020 At the Intersection of Racial Justice in Education, 4 Keys to Talking About Racism in Schools: #4 AdaptabilityRead NowThis is the final post in our 4-post series featuring Dr. Cherie Bridges Patrick’s research on the four capacities that can enable us to have generative racial dialogue. Please read the others! You’ll find part one that discusses the importance of a positive, encouraging, liberating dialogic environment here, part two, on the readiness and willingness to engage in antiracism and racial justice work, here, and, part three, on vulnerability here. Today’s post will focus on the fourth and final discourse capacity: adaptability. Let’s dig in. Adaptability. This capacity comes from Heifetz, Grashow, and Linksy’s (2009) work on adaptive leadership.They argue that one of the biggest reasons for leadership failure is trying to meet an adaptive challenge with a technical fix. They define an adaptive challenge as, “the gap between values people stand for (that constitute thriving) and the reality that they face in their current lack of capacity to realize those values in their environment.” Dr. Bridges Patrick challenges the common desire for many White people to commit to colorblindness or to the notion that racism is about the individual noting that it limits people’s ability to “efficiently identify, talk about, and address systemic challenges.” Heifetz and his colleagues contextualize this within their adaptive challenge idea, writing, “[We] resist dealing with adaptive challenges because doing so… requires a modification of the stories [we tell our]selves and the rest of the world about what [we] believe in, stand for, and represent.” According to Dr. Bridges Patrick, building up this adaptive capacity requires us to engage in critical self-reflection and praxis (applying theory in practice), accept living in a state of moderate uncertainty, be open to shifting our “priorities, beliefs, habits, and loyalties”, and engage fully with our whole selves, body, mind, and spirit. What does this look like in educational spaces? From the perspective of adaptability, Dr. Bridges Patrick suggests that technical fixes and practices consist of responses, beliefs, and practices that contribute to maintaining the status quo. These are well-known, commonly accepted routines that are practiced without conscious thought. She says, “take Sophia in my study, for example. She was a Black professional committed to antiracism who worked with an all-white medical team. Using a longitudinal study, Sophia presented the ways racism impacted the kind of medical care African Americans received. What Sophia experienced with her team in that moment was performative silence: “I just shared an article with my team that just came out of a longitudinal study that looked at [medical care] for African Americans and the ways that racism impacts the kinds of care they get, how soon they get a [medical] diagnosis . . . all of those things and so I gave them the article and I broke it down and they’re like, oh, this is really very interesting.” The silence was an unspoken, group agreement to avoid a potentially informative conversation about improving health care. There are too many other challenges that arise from this scenario for me to explore, but one is the impact the silence had on Sophia, members of the team, and the patients they served. Sophia ended the story by saying “you would have thought I threw a bomb in the middle of the room”. Adaptability then is both an individual and group or organizational characteristic that moves beyond technical, implicit processes. Applying adaptability to the previous scenario in the context of antiracism would have required someone in the group to do something different. Rather than remaining silent, an adaptive response may have encouraged a question to advance a conversation. Adaptive capacity is having the skills necessary to fill the gap that exists between aspired values and living those values into existence. Within the adaptive individual or team/organization is a container or structure that welcomes and supports new ways of thinking and practicing. This flexibility shifts, expands, and shrinks to allow for imagination, time for critical reflection, making and recovering from mistakes, and evaluation and adjustment of new or different practices. Adaptability means interrogating our long-held beliefs about how school is done and what school should look like. It means critically examining disconnects between what we say we value and what our policies, pedagogies, and assessments indicate we actually value. It means having a structure (leadership, resources, etc.) that supports this kind of work and a plan to navigate the resistance that will surface to maintain the status quo. Let’s take one example of each. Policies. If we say our primary mission as an organization is to educate all students, but our dress code sends students (disproportionately Black female students) out of the classroom, we are not actually prioritizing students’ education. Instead, we are valuing conformity to the dominant (read: white) norm about how students should dress and groom themselves more than ensuring students learn educational standards. Pedagogies. If we say we value student engagement, but we (teachers) talk for the majority of the class time, lecturing and asking students to remain silent, and never asking for critical feedback from students, we actually value obedience to authority (often, white authority) more than student voice and engagement. Assessments. If we say we value creativity and critical thinking, but we grade students by how well they answer factual multiple choice tests, we actually value memorization and regurgitation of content more than an ability to creatively apply concepts to novel situations. (The use of standardized tests has not served as an accurate measure of students’ abilities, namely students who have been grossly underserved by our education system, many of whom are our Black, Latinx, and Indigenous students.) An adaptive approach to racial justice requires a bold, imaginative vision. Hopefully the increased visibility of antiracist work and its importance will serve as what Mezirow calls a “disorienting dilemma,” an experience that doesn’t fit with a person’s expectations or beliefs. Many educators may have believed their schools were working for racial justice, but upon further examination, are becoming aware their schools are perpetuating white supremacy. We hope you can use this moment to call others into the work, collectively identify racist policies and practices, and collaboratively dismantle them. To help you, we’ve put together a resource list. Finally, although this is the last post in Dr. Bridges Patrick’s 4-post series on the Time for Teachership blog, we can all continue to learn from her! You can follow her on Instagram at cheriebpatrick, on LinkedIn, or visit her website. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed