|

In the last two weeks, I’ve facilitated several virtual workshops on culturally responsive teaching and systemic racism. These particular workshops were focused on increasing awareness of racial injustice and learning how to first identify the problems. This is an essential first step, developing our understanding of the complex ways racism has been embedded into the fabric of institutions like school. However, many of us want to know what to do. Dr. Cherie Bridges Patrick has taught me that you first need to sit with it and truly seek to understand the complexity of the problems before jumping right to action. So, recognizing we need to do that first, I’ll do my best to answer what is becoming the most common question asked of me during racial justice workshops: “Once I have an understanding of the problem, what can I do about it?” Before diving into action steps, let’s look at a framework that may help us understand the variety of ways racism can play out in educational spaces. This framework is called the Four I’s of Oppression. (Described in detail here.) Here’s a brief summary:

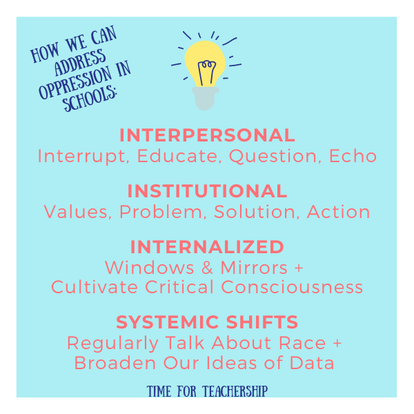

When we understand the different forms oppression can take and we recognize they are all interconnected, we are better able to form a plan for action. In the Moment Since ideological oppression is the idea that emerges through the other three I’s, I will focus here on what we might do when we see these other I’s in our schools. Addressing interpersonal oppression. Teaching Tolerance has a “Speak Up” pocket guide (linked here) that suggests four actions you can take when you witness someone do or say something racist. The four actions are: Interrupt (say something like “That phrase is hurtful”); Question (ask “Why do you say that?” or “What do you mean?”); Educate (explain why it’s harmful); and Echo (if someone else speaks up first, back them up with a simple “Thank you for speaking up. I agree that’s offensive.”) This pocket guide was actually designed to support students in speaking up, so you can use this with students as well! Addressing institutional oppression. Initiating policy change requires a multi-step approach. Although, some of the previous suggestions could serve as an initial step. For example, if you want to bring up a problematic policy, you might plan to say something at an upcoming meeting. You might pose a question like: Is the dress code helping all students learn? Then you can ask another teacher to be your echo so you are not positioned as the only person who sees this policy as a problem. When constructing your initial message, I like the approach developed by Opportunity Agenda, an organization that helps writers effectively communicate messages about social justice issues. They suggest this formula: Values, Problem, Solution, Action. Here’s what this might look like: “We’re all here because we want to help each of our students get the best educational experience possible. When students are removed from class due to dress code violations, they are losing instructional time. The latest data shows x number of students were removed from class last week for at least y minutes, and z number of students were sent home to change, missing hours of instructional time. To make sure our policies are maximizing student learning, I think we should start a committee to take a closer look at the dress code. This committee should include teachers, students, and families so that everyone who is affected by this policy has a voice in this process. It’s important to ensure our action reflects the inclusion and equity we want from the policy change. (For more on this, check out my previous post on shared leadership structures.) Addressing internalized privilege/oppression. Responding to internalized privilege and internalized oppression will require different approaches. For privileged students to recognize their privilege, you may want to introduce white privilege as a concept and highlight this is one way in which white supremacy manifests. Depending on the age of your students, the list in Peggy McIntosh’s article may be a helpful place to start. White students will also benefit from hearing stories and learning about the experiences of people of the global majority. Windows and Mirrors is a powerful approach with which to analyze your curriculum to ensure all students can have windows into stories of people who do not hold the same racial identity. This lens is also valuable for addressing internalized oppression, as Black, Brown, Indigenous, Asian, and AMEMSA (Arab, Middle Eastern, Muslim and South Asian) students need to see positive and complex representations of their racial groups in the curriculum. This Teaching Tolerance article also suggests explicitly debunking stereotypes and racialized myths, which cultivates students’ ability to be critically conscious of unjust representations of racial groups in textbooks or media. The article also distinguishes low self-esteem from internalized oppression, which is an incredibly important point. Whereas we may support a student with low self-esteem to see themselves in a more positive light, that’s not enough to address internalized oppression. We must help students recognize it for what it is: internalized oppression, stemming from ideas of white supremacy. We can help students identify how these stereotypes are perpetuated and who/what purpose these ideas serve. Systemic Shifts Acting in the moment is often what we think about when we wonder how we can respond to racism in schools. It’s certainly an important capacity to build. However, changing the broader school culture, shifting the system itself, can reduce the likelihood of racism moving forward. We don’t always want to be reacting. We want to find ways to be proactive. Make time for ongoing meetings about racial justice. One way to shift the culture is to make time for conversations about race with colleagues on a regular basis. As educators, we never have enough time to get everything done, so it may be challenging to see “adding” something else as doable. But racial justice isn’t something we’re adding to our plates. We are constantly “doing race” in our daily interactions. It’s embedded into everything else we do. If we can recognize this, we will see the importance of looking at our policies and data through the lens of its racialized impact. Through these conversations, schools can develop a culture of productive dialogue about issues of race and individual educators can build their capacities to see the complexity of racial injustice, including all of the identities that intersect with race to produce unique experiences of schooling for Black girls or queer Indigenous students, or Latinx students with dis/abilities, or transgender white students. Broaden the school’s conception of data. When we think of data, as educators, we often think of standardized test scores. Perhaps report card grades. Possibly graduation rates. Rarely do we move beyond this to consider other sources of data. Individual teachers may collect qualitative data from students and families throughout the year, but this is not usually systematized. We don’t usually look at qualitative data on a school-wide basis. Broadening our ideas of what types of data are valuable requires us to be clear on what we value as a school. Looking at standardized test scores, report card grades, and graduation rates reflects the importance we place on educational outcomes. Might we also want to look at how students and families experience schooling? Could we collect survey data and hold interviews or focus groups with students and families around questions of the degree to which they feel they belong in school or their voice matters? Asking what data matters and who we should gather data from can generate powerful shifts in thinking about how schools measure “success.” Inspired by Teaching Tolerance’s "Speak Up" pocket guide, I’ve made a pocket guide for this blog post to share with colleagues or keep as a handy reminder of the types of oppression and actions to take to address them. As we all grow and learn from one another, I invite you to share your ideas and experiences of identifying and dismantling racism in your schools.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed