|

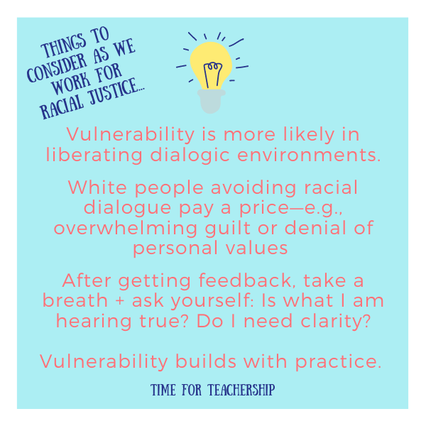

6/29/2020 At the Intersection of Racial Justice in Education, 4 Keys to Talking About Racism in Schools: #3 VulnerabilityRead NowThis is part 3 in our 4-post series featuring Dr. Cherie Bridges Patrick’s research on the four capacities that enable us to have generative racial dialogue. You can read Part 1 here, which focused on the importance of a positive, encouraging, liberating dialogic environment and Part 2 here, which focused on a readiness and willingness to engage in antiracism and racial justice work. Today’s post will focus on our recent discussion about the third discourse capacity: vulnerability. To define vulnerability, Dr. Bridges Patrick uses Brené Brown’s (2006) grounded theory work on shame resilience in women, in which she refers to vulnerability as being “open to attack.” As mentioned in the previous post, antiracist work is not without risk. Dr. Bridges Patrick writes, “the characteristics of facing vulnerability and risk include ability to trust (in the process, people, or one’s own ability), and ability and willingness to articulate fears and internal conflicts” (2020, p. 167). Vulnerability in the context of racial dialogue is more likely to happen when the discourse environment has been sufficiently prepared. Part 1 of our 4-post series offers a description on the dialogic space. A white participant in Dr. Bridges Patrick’s study reflected her fears, first related to her ability to carry out the work then on the impact that calling out racism at work can have on one’s collegial relationships, saying: “I have a fear of if I get into this what is that going to entail, it’s going to be a lot of work. And also to be perfectly honest, how are my coworkers going to look at me if I’m always the one bringing this up, and . . . can I take that on myself? I shouldn’t be putting it on other people to bring it up . . . everyone individually should be doing it, but it’s hard and you don’t want to be that person.” When talking about race, vulnerability seems particularly difficult for white people. Why? There are numerous perspectives as to why vulnerability is a particular challenge for White people. Some readers are aware of how Robin DiAngelo describes the phenomena in her book, White Fragility. She writes “As I move through my daily life, my race is unremarkable. I belong…It is rare for me to experience a sense of not belonging racially, and these are usually very temporary, easily avoidable situations” (2018, pp. 52-53). DiAngelo suggests that people who are Black, Brown, Indigenous, and Asian do not have this luxury, rather they have been forced into situations of discomfort, where they are “open to attack.” DiAngelo also gives an example of the ease with which white people can opt out of chances to exercise vulnerability, stating, “Many of us can relate to the big family dinner at which Uncle Bob says something racially offensive. Everyone cringes but no one challenges him because nobody wants to ruin the dinner...In the workplace…[we want] to avoid anything that may jeopardize our career advancement” (p. 58). These are examples of white solidarity which uphold white supremacy. White people need to make the conscious choices to put ourselves into these situations. Dr. Bridges Patrick offers her perspective on why vulnerability is so difficult for White people. There is so much to respond to in these two very rich statements by DiAngelo although, I will limit myself to two comments. I posit that it is not a luxury for White people to remain absent from racial dialogue. I do acknowledge the material and psychic gains that Whites regularly receive, yet at what cost? Those who have been sincerely interested in antiracism work, have likely, at times, experienced overwhelming guilt or have denied personal values in exchange for the acceptance of family and/or social values, for example. White people are concerned with being perceived as racist (van Dijk, 2008). In my work on racism denial, a strategy of defense often presented by Whites is positive in-group presentation, or face-keeping (van Dijk, 2008) that is performed to present an image of ‘not-racist’ or an image of goodness. Denial is also used to accentuate peoples roles as competent, decent citizens (van Dijk, 1992). Both arguments as to why vulnerability for Whites remains impenetrable potentially end up with the same or similar results yet the strategies to get there are different. When we make ourselves vulnerable, sometimes we may receive critical feedback. What’s an appropriate response? The work of antiracism absolutely requires feedback so we would be wise to welcome it. How we respond to feedback that others have been negatively impacted by our words is critical. Dr. Bridges Patrick offers this perspective: when feedback stings (and it will) before I verbally respond, I first pause, take a deep breath, and notice what is happening in my body. The first questions I ask myself are “is what I am hearing true?” and “do I need clarity?” Responding with tears, defensiveness, or hostile body language does little to further generative conversation, although it can invite other participants to return to the shared agreements that were developed at the beginning of the conversation. The purpose of feedback is to challenge patterns of thinking and behavior and to support growth. That’s the goal—to be better not to remain stagnant and steeped in the “smog” (Daniel Tatum, 1997) of racism we all breathe. How do we build up our capacity for vulnerability? Dr. Bridges Patrick says we need to “[grapple] with conflicting values and perceptions, particularly how [we] might be perceived by peers” (2020, p. 208). Discussions around race and racism engender emotions...remember that “race is a construct with teeth” (Menakem) while racism continues to wreak havoc on our lives, relationships, systems and souls. This means we must practice in those liberating dialogic environments or with an accountability partner. If we think about what has contributed to difficulty with engaging in productive conversations around race we find that many White people have not been having them, and quite honestly, some of us would rather not have them. When race becomes a topic, the example below is a common way race is brought up by White professionals in the workplace. Sophia, an African American, is responding to the question of when race comes up at work: “It comes up when there’s a problem, or, and I shouldn’t say a problem, but a challenge. So . . . let’s say there’s a patient who’s having some issues with safety in their neighborhood, then it’ll come up and somebody will say for example— because we level our community—so level one, high alert safety is really concerned about the neighborhood. So they’ll say, well, this patient is new to me and now, I’m not, you know, please don’t take this the wrong way, I’m not saying it’s because she’s Black you know, so that’s how it usually comes up.” How do we support our students to increase their capacity for vulnerability? Building our own muscle for generative racial dialogue is one of, if not the most important element for supporting increased capacity for students. In the first post of this 4-part series, we included a free resource to help teachers set class agreements that would support fruitful conversations about race and racism. In White Fragility, DiAngelo highlights common discussion agreements that she says are ineffective. As teachers, we can spend some time here, clarifying through class discussions what we as a class mean by our co-constructed agreements. For example, DiAngelo says “assume good intentions” is a problematic agreement because it positions intent over impact (not to mention that intent cannot be substantiated and is often used as a strategy of denial). Donna Hicks’ seventh element of dignity offers an alternative, “Benefit of the doubt.” While these two points might at first glance seem contradictory, they are not. We can, as Hicks says, “Start with the premise that others have good motives,” while also focusing on impact over intent. As educators, we want to make time for these important conversations about nuance with our students, so they can effectively engage in conversations about racism. Using what you’ve learned in this series and in other readings about antiracism work and racial dialogue, start making a list of points or clarifications you want to bring up when you and your students develop your class agreements together in the fall. Although only class agreements are mentioned here, in any planned group racial dialogue there should always be a discussion around rules of engagement. A perspective offered by Dr. Bridges Patrick notes that “one of the ways I start that particular conversation is to first position dignity and honoring each person’s humanity as non-negotiables. I then ask the question: What do each of you need to have honest, vulnerable conversations about race and racism?” As Dr. Bridges Patrick eloquently writes in the closing to her dissertation, “dominance does not sleep nor does it vacation, rather it feeds off of fears and ignites the propensity to look away from its reality. Simultaneous to this is the silent presence of resistance that must also receive attention” (2020, p. 218). Thus, we must look inward to deeply reflect on our values, refuse to look away, and build our capacity for resistance.

0 Comments

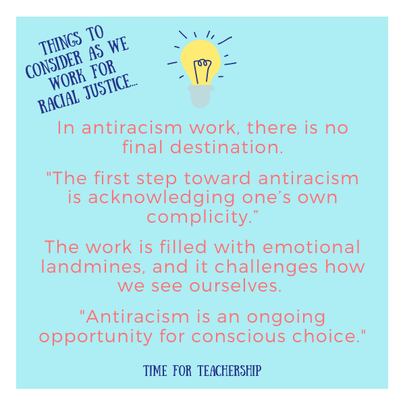

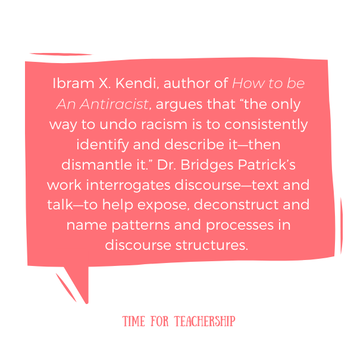

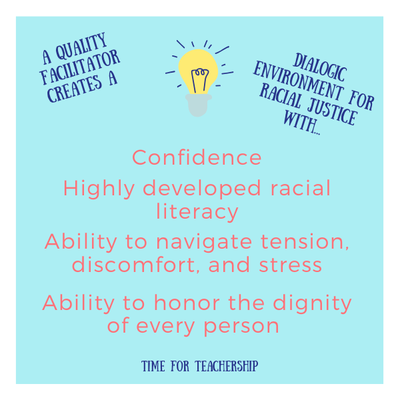

6/25/2020 At the Intersection of Racial Justice in Education, 4 Keys to Talking About Racism in Schools: #2 Readiness & WillingnessRead NowOur last post introduced the work of Dr. Cherie Bridges Patrick, who is co-authoring a 4-part series of posts on the intersection of racial justice in education. If you haven’t read that post, please do! It offers a great frame for the rest of the posts in the series. In that first post, Dr. Bridges Patrick shared four capacities that contribute to fruitful racial dialogue, which emerged from her research. To recap, they are: 1) readiness and willingness; 2) vulnerability; 3) adaptability; and, 4) a positive, encouraging, liberating dialogic environment. Each of the four posts in this series examines one of the four capacities. Today’s post will discuss: readiness and willingness to engage in antiracism and racial justice work. The term readiness and willingness may seem intuitive, even simplistic, yet in the frame of racial justice work it is complex. Given its complicatedness, we’ll briefly explore the meaning of this capacity. We will connect them to having generative racial dialogue in our next two blog posts. Let’s hear from Dr. Bridges Patrick about readiness and willingness. Let’s be real...who really wants to have honest, raw conversations about anything? A major part of my work and research is around exploring and interrogating racial dominance and I have come across very few people who are prepared to think and reflect deeply about it because it is HARD work. That we are in this moment, at this time is evidence of the ways the truth of race, its origins, its evolution, its abuse, and its power have dominated our lives. Readiness & Willingness. In the context of racial justice, readiness and willingness is being prepared to proceed on a journey for which one never “arrives.” So what does it mean to be ready when there is no final destination? Where do you start? Given the complex, ubiquitous, evolving nature of racial dominance, this is what I would say with the knowledge that I have today. Any topic or work that revolves around race - dialogue, education, healthcare, voting, trauma, healing, policy change, for example, often causes a visceral reaction from many people. From this perspective then, we can view race as a social “construct with teeth” (Menakem, 2020). Numerous educational scholars (hooks, 1992; Jeffery, 2005, 2011; Jeyasingham, 2011) agree that challenging racial inequality through everyday education and instructional practice requires a struggle with core tensions related to race—arguably the most fraught aspect of difference and inequality in American society (Guiner & Torres, 2002; West, 1993). Do Your Own Work - With Accountability Recently, increasing attention has been paid to antiracism and racial justice, and there are numerous resources available (we will provide a brief list in the next blog). For starters, asking oneself a few questions is always helpful. Stop & Think: Why am I (thinking about) doing this work? What is my motivation...honestly? There is ample evidence to suggest that addressing long-standing racial inequities in a substantive way has not been a priority for many...why is this the case and why now? Race scholar Ibram X. Kendi tells us that many Americans are committed to an idea that there is a neutrality – a place where there is no complicity. This idea presents quite a hurdle, particularly because he tells us the first step toward antiracism is acknowledging one’s own complicity. Stop & Think: Let that sink in…”the first step toward antiracism is acknowledging one’s own complicity.” What does that even mean? According to Kendi you’re either working toward antiracism or not. As for the work...doing your own work absolutely requires a thorough on-going inquiry into your own racial identity, history, experiences of internalized racism and whiteness, and how they have and continue to operate in your life. In my role as a leadership coach, accountability from someone who is vested in the growth of others is critical. We tend to think more highly of ourselves and accountability offers opportunities for processing and allows for a more rational (though imperfect) perspective. Accountability is especially useful for those who are in the early stages of antiracism work. A commitment to racial justice is accompanied by risk. Racial dialogue is filled with landmines of emotion for which many are not prepared to navigate. Stop & Think: As you read this, notice what is happening in your body...what physical sensations are you experiencing? (e.g. tension, pain, headache, fatigue, etc.). These sensations are often uncomfortable so many of us avoid them. Loss is a big theme on this journey and it is experienced in many different ways. For example, several years ago a White middle-aged colleague expressed grave fear about wearing a Black Lives Matter t-shirt around her family as she believed they would disown her. Dissonance will make itself known. For example, our identities will be challenged leaving us to face that the kind of person we believe we are is very different than what our actual day-to-day behavior reveals. Uncertainty is likely to become a prominent feature leaving us to guess at what to do in any given moment. Readiness and willingness then encompasses the commitment, purpose, tenacity, and resilience that is necessary to engage in antiracist dialogue and practices. In his book, How to Be an Antiracist, Kendi (2019) tells us that “the only way to undo racism is to consistently identify and describe it–and dismantle it.” Antiracism then is a process that requires ongoing, consistent, intentional observation of our thoughts, words and actions, how they function within us and how they impact others and the larger society. We can view the concept of readiness and willingness as a developmental process that runs parallel to the work of antiracism. Every stage of antiracism work requires an ongoing and evolving recommitment to that process. From this perspective, antiracism is a perpetual opportunity for conscious choice. For teachers, our readiness and willingness are critical to developing racially just schools, creating antiracist policies and pedagogy, and how we talk in the teacher’s lounge. Readiness and willingness means there is a conscious acknowledgment that we are willing to live in uncertainty, willing to fail, to try again, to fail better, and to try better. We often close our posts with an action item, but the action you can take now is to re-read this post, paying particular attention to the “Stop & Think” prompts. Jot an “aha” down on a post-it note, and return to that key idea as you continue to work for racial justice in your schools. 6/22/2020 At the Intersection of Racial Justice in Education, 4 Keys to Talking About Racism in Schools: #1 A Liberating Dialogic EnvironmentRead NowThe demand for racial justice is loud and clear. The concept of antiracism has transformative potential to realign and invigorate conversations around racism and can direct us toward “liberating new ways of thinking about ourselves and each other” (Kendi, 2019). As we plan to make our schools sites for antiracism work, we may wonder where we should focus our action. I’ve written previously about critically examining our policies and pedagogy, but we also need to be able to strengthen our ability to have generative racial dialogue—with colleagues and students. For advice on this, I turned to my brilliant colleague, Dr. Cherie Bridges Patrick. Her research on racism denial in workspaces examined the ways in which racial dominance is (re)produced in everyday professional interactions, often without intent. We have combined our expertise to merge racial justice into all aspects of education. In the course of her research, the term racial dominance is used to express the combination of racism and whiteness. These are complex concepts, in part because their destructive nature is obscured and often consists of what is not said, what is not obvious, or what is imperceptible. Ibram X. Kendi, author of How to be An Antiracist, argues that “the only way to undo racism is to consistently identify and describe it—then dismantle it.” Dr. Bridges Patrick’s work interrogates discourse—text and talk—to help expose, deconstruct and name patterns and processes in discourse structures. In talking to Dr. Bridges Patrick, I asked what educators could do to address the issue of perpetuating systemic racism and the dominant presence of whiteness in schools. The first step in identifying and describing racism requires an ability to talk about it. She recommends building educator capacity to effectively engage in productive conversations around race while also ensuring measures of accountability for schools and educators who commit to doing this work. Four capacities or characteristics that contribute to fruitful racial dialogue emerged from Dr. Bridges Patrick’s research: 1) readiness and willingness; 2) vulnerability; 3) adaptability; and, 4) a positive, encouraging, liberating dialogic environment. First, let’s unpack the most foundational element of racial discourse capacity building...a positive, encouraging, liberating dialogic environment. What does that entail? Driving the necessity of a dialogic environment is the notion that many of us don’t know how to talk about race, which often results in various forms of denial including willful avoidance and silence (often driven by a desire for comfort). An example of a denial strategy is offered because they are often present in racial dialogue. In her thematic analysis, Dr. Patrick found several discourses of denial, one of which was comfort/discomfort. Discourses of comfort/discomfort are about maintaining white comfort without consideration of the costs to others. Emergent data suggested that comfort served to prioritize the needs of white professionals at the expense of their non-white colleagues. Comfort is often undergirded by fear and insufficient skills to navigate the discomfort of racial dialogue. A white professional in the study stated: “there’s a fear, I think that kind of what I was talking about before, like, there’s this elephant in the room, but you’re scared to like say the wrong thing… step on someone’s toes, be perceived as racist.” Building skills to navigate racial dialogue will be part of the upcoming discussions on the interpersonal aspects found in the remaining three discourse capacities. Positive, Encouraging, Liberating Dialogic Environment. The dialogic environment is led by a confident facilitator with highly developed racial literacy and an ability to navigate the tension, discomfort, and stress that accompany racial dialogue, while honoring the dignity of every person. When describing this type of environment to me, Dr. Bridges Patrick clarified that this is not a “safe space,” but a generative one, one that is free of physical and emotional violence and exudes an atmosphere where people can be vulnerable. In her research, she further explains this environment is not specific to one space. She writes, “Whether a classroom, office space, or coffee shop, the environment can be liberating when grounded in dignity, and the humanity of all is recognized and honored.” This environment includes online environments given our current shift to distance education. She continues, “The liberating dialogic environment is a space where tension, conflict, and challenge are invited and used for information and transformation. “The dialogic space is one where disagreement is needed and must be expected, and strong emotions are seen as expression rather than personal attacks” (Bridges Patrick, 2020, p. 172). Feminist scholar and social activist bell hooks (2000) supports the need for disagreement. She argued that work around revolutionary feminist consciousness-raising could occur “only through discussion and disagreement,” from which participants could begin to gain a “realistic standpoint on gender exploitation and oppression” (p. 8). The work of antiracism requires a similar stance. Amidst the serious nature of racial discourse, Dr. Bridges Patrick also highlights, “Laughter is critical to this work and the environment should allow for levity.” In Dr. Bridges Patrick’s research focus group, emotions were invited while dignity and humanity were positioned as nonnegotiable by these comments: “We can be angry, we can be frustrated, we can be whatever . . . but, at the end of the day, when we leave this Zoom room, we should all have our dignity and humanity intact and recognize that shared humanity” (p. 172). Facilitating a space for racial dialogue requires the centering of dignity - the notion “that all human beings are imbued with value and worth” and a sense that all persons are honored as contributing to the collective (Hicks, 2011, p. 4). Honoring the dignity of others is not connected to the unique qualities or accomplishments of people, rather it is the belief in one’s inherent value and worth no matter what they do. Dignity then is an intrinsic part of being alive and cannot be granted through authority, only honored or violated (dishonored). Treating people poorly because they have done something ‘wrong’ perpetuates the cycle of indignity and we violate our own dignity in the process. To help you further understand the elements of dignity as you engage in conversations ripe with disagreement, we’ve put together a free resource you can use with colleagues and with students. Click the button below to get a 1-pager, summarizing Dr. Hicks’ 10 elements of dignity as well as a student-facing poster of the elements, which can be a great starting point for developing class agreements next year. I always find it helpful to ask students to share their experiences of the year—the good, the not so good, the ideas for improvement for next year, anything else that feels relevant to share. I think it’s helpful to ask for student reflections throughout the year too (e.g., the end of each unit, after introducing a new protocol). So, let’s think about how you could ask your students to reflect on this school year. What to Ask What did you miss most about in-person classes? (You can make sure you do more of whatever it is kids missed next year.) What were the best parts of distance learning? (There’s a chance we’ll be continuing remote learning to some degree next year, so, note what worked for students and do more of that in the future. Of course, different students may say different things, so consider ways to provide multiple options for engagement so all students can have an opportunity to engage in the way that works for them.) What was difficult for you during distance learning? (Depending on how you word this question, you may get some responses that are out of your control. Focus on what you can control and identify possible areas of support you can offer in the future.) If we had to do the last 3 months all over again, what would you want me (as the teacher) to do differently to help you learn better? (Students often come up with great ideas here. List them all out, and remember some students’ responses may contradict one another, so offer choice where possible as you plan how you’ll implement these suggestions in the future.) What else do you want me to know? (You can be specific here and focus on students’ personal experiences during the year, the best part of the year, what you hope for next year, etc.) Feel free to make the questions your own and add others, but I would start with these basic concepts (successes, challenges, and suggestions). How to Ask Students could respond to these questions in a variety of ways. Worksheet or Journal Entry. Students could complete a worksheet set up as a Google Doc (or Word Doc) with space to respond to each of these questions. Even more open-ended, you can provide the questions as journal prompts and have students write a journal entry addressing these in whatever way and to whatever degree they wish. Form. You could create a Google Form (or Microsoft Form) with these questions set up for open-ended responses or prefill checkbox options, so students can have a list of ideas to choose from if you think they may struggle to come up with ideas on their own. I suggest leaving space for elaboration in the form of an open-ended response question following each checkbox-type question. An added benefit of having the checkbox options is that you can see a graphic representation of the data, which helps you pick out the trends more easily, and you could share these visuals with your students. Here’s a free, Google Form template you can adapt and send to your students: Note: When you sign up for this resource, you will get access to a Google Drive folder with the form inside. You don’t need to open the form. Instead, you will right-click on the form and select “Make a Copy.” This way, you can make it your own! (I know this is clunky, but right now, it’s the only way I know of to share a form, as there is currently no view-only link sharing option in Google Forms.) Video. Students can respond to the prompts using a tool like Flipgrid, which will support your students who may struggle with writing to provide their ideas. If you want responses to be private, you can select the grid setting to require you to approve the videos before other students can see them, and then just don’t approve any videos. If you did want to share the video reflections with families or your administrators, you have the option to add each video to a “Mixtape” and share out the compilation of responses. Subject-Specific Representation. Students could create a piece of art that represents the year and caption it in a way that addresses the question. Students could create a math equation or recipe for the best ingredients for learning from home. Students could write a song or a poem about their experience. Get creative here! Student Choice. While we’re talking about student voice, you could also provide each of the above options (plus additional options you come up with) as choices on a choice board. Students can choose which way to share their feedback. You could also provide students with a “free choice” space where they come up with a creative way to share their responses to these reflection questions. Once you’ve collected all of your data, share the wealth of student knowledge with other teachers! Share themes that came out of student reflections in the comments below or in our Time for Teachership Facebook group. One of my amazing professors at Antioch University, Dr. Jon Wergin, held a webinar several months ago, and I finally finished watching it. As I listened, I couldn’t stop thinking about how relevant Wergin’s points were to the current situation in education. You can watch the full webinar here. In this post, I want to summarize the key points from the webinar and identify how the events of the last few months lend themselves to creating constrictive disorientation for educators in order to spark long-term systemic change in our schools and the larger educational system. What is constructive disorientation? Wergin defines constructive disorientation as “an experience that unsettles us and sparks our curiosity, both at once; and does so in a way that we perceive an opportunity to change how we see the world, and for the better.” Where does it come from? Wergin says constructive disorientation can come from what Mezirow calls a “disorienting dilemma,” an experience that doesn’t fit with a person’s expectations or beliefs. But, Wergin says, “we don’t necessarily have to wait for a disorienting dilemma to hit us over the head and force us to pay attention.” He suggests a practice of mindfulness or critical reflection can surface smaller kinds of disorientation. A third source of disorientation, he says, is an “aesthetic experience” (e.g., a piece of art) is a change for someone to try on the perspective of an artist “at low risk” to one’s self. He gives the example of Kehinde Wiley’s Rumors of War statue, installed down the road from Richmond, Virginia’s Monument Avenue. How do recent events promote constructive disorientation? Wergin says there needs to be a disruption in routine. Nation-wide school closures have definitely disrupted how education is done. Protests over the deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor have once again reminded us that this country is not a safe place for Black children. This may serve as a disruption for some educators who did not previously realize the extent of violent racism that exists today or had not previously been asked to discuss racism in their classes. What else can we do to make the disorientation constructive? Wergin says the challenge needs to be clear, but manageable. In terms of clarity of the challenge, some teachers may already see the need for a long-term shift in pedagogy following school closures and an intentional focus on anti-racist pedagogy. Others may benefit from one of the suggestions above (e.g., opportunities for reflection or mindfulness practice or artwork depicting students’ or family members’ ideas of what school could be). In terms of manageability for distance learning, at first, many educators were in a panic trying to figure out how to get their classes up and running in virtual spaces. After two months of adapting instruction to work in a distance learning setting, it’s likely teachers are closer to that ideal level of anxiety—just enough to want to do something about it, but not so much that it’s debilitating. The same goes for conversations about racism in schools, teachers may initially shut down, but as leaders, we want to present opportunities for conversation in which teachers can experience that anxiety and practice talking about racism with adults to be able to more effectively facilitate conversations with students. Leverage (or build up) your staff’s social capital. Wergin says there is a direct correlation between the amount of social capital in an organization and the degree to which meaningful conversations can be had. In order to get teachers to reflect on this disorientation and listen to others’ points of view with empathy, thee needs to be: a sense of shared fate (remind everyone we’re all here for all kids); ideological diversity and an openness to hear contributions from all members (norm listening and focus on identifying shared goals and underlying values before debating how to move forward while also acknowledging that white folks are not the authority on what it means to be Black in the U.S.); and a collective responsibility for success (consider posing a question like: What can I personally do to help us move forward as a school?) Make time for the conversation. Research tells us we learn best in the presence of others, when we can try on others’ perspectives. For some schools, a natural time for this may be during scheduled testing week (which, for most, has been cancelled). For others, this might be summer, when lesson creation and giving feedback to students are no longer daily concerns. Wergin says it’s necessary to have a setting conducive to deep work, so teachers can deeply concentrate and not be distracted by logistical tasks like checking email. Take other tasks off teachers’ plates if needed so they can be fully present in the conversation. Facilitators of this conversation will want to keep an eye on the levels of anxiety to keep folks at the edge, but not let people fall over it. Wergin says to maximize autonomy of participants, so you may provide multiple ways teachers can participate in conversation (small group, whole group, writing activity like Collect and Display). Finally, give teachers the freedom to try and fail. School building closures have helped many leaders do this better than ever. When we’re all trying to learn how to do something new with little preparation, we tend to be (or we should be) more forgiving when things don’t go perfectly. This is also true for anti-racism work. We cannot allow our fear of failure prevent us from taking action. In conversations with teachers, encourage teachers to share their successes but also to share things they tried that didn’t work. Focus on extracting the learning from those experiences. Celebrate teachers for trying and being committed to growth. Keep this attitude in mind for next year when considering how teachers will be evaluated. Is there a place on your evaluation rubric for informed risk-taking? Is anti-racist pedagogy an aspect of the evaluation rubric? If you want teachers to try something new, will you reward them for trying it even if they fail? Or does the criteria on which they are evaluated as teachers promote rigidity and conservatism? Wergin talks about goal displacement in the education system nationally by using the example of standardized tests—when we say we value student problem solving and creativity, but students are defined by one high-stakes test measuring rote memorization, those things we said we value are replaced by what is measured. This emergency transition to distance learning, anxiety about COVID-19, and the latest instances of racist violence have certainly disrupted our classes and our school communities. But, as leaders, it’s up to us to find ways to use this disruption to foster post-traumatic growth. We can use these events to create “constructive disorientation,” and from there, spark long-lasting change that better serves all of our students. Many educators have been sharing resources and suggestions for talking to students about racism and police brutality in the last few weeks. We absolutely need to continue having these conversations with our students. We also should be asking what we can do to address the problem of systemic racism. I’m trying to use my area of expertise to focus on anti-racism work in educational contexts—taking steps to identify and eliminate places where our schools or classrooms are perpetuating systemic racism. Often, these practices are unintentional and involve a lot of self work. We may need to read up on the practices that perpetuate the opportunity gap, and un-learn these practices while we learn better ones. In this post, I’ll share some of the major pedagogical shifts for you to consider as you think about how your school can advance educational equity moving forward. As you read, consider the hat(s) you wear in your school—teacher, department chair, instructional coach, administrator—and think about what you can do in your role to support larger shifts towards equity, in your own classroom and across the school. What does the research say? First, educational inequity exists. Black and Brown students, students new to English, low-income students, students with IEPs (National Center for Educational Statistics), and transgender students (Gender Spectrum) are being severely underserved by traditional educational systems. Second, we can identify practices that cause this marginalization. Some practices are school-wide policies. Discipline policies that keep students out of classes for non-violent acts, like not following codes or acting “unfeminine,” are disproportionately pushing Black girls out of schools. Preventing students from using the bathroom that aligns with their gender identity or failing to provide gender neutral bathrooms leads to trans students avoiding bathrooms or avoiding school itself. Other practices that perpetuate inequity are pedagogical. Our approaches to grading, curriculum design, and partnership with students are all practices to interrogate. Let’s take a look at each. Grading practices. Grading student work holistically instead of analytically (i.e., a grade for each standard being assessed) leads to unintentional educator bias, which often perpetuates the so-called “achievement” gap. Grading each of the year’s assessments with equal weight (instead of weighting end-of-year grades more than start-of-year grades and replacing draft submission grades with revised work grades) perpetuates the opportunity gap because this approach to grading does not value academic growth over time. Instead, it rewards students who entered the class on (or close to) grade level and punishes students who were already behind. Teachers who measured skill growth over time on mastery-based scoring scales noted a 34% gain in student achievement compared to traditional grading systems. Curriculum design. Traditional “sit and get” instruction followed by graded quizzes may continue to disengage students who have, historically, not had success in school. However, research on project-based learning as an instructional strategy has seen positive results for historically low-performing students. PBL classrooms have higher student engagement, student motivation to learn, student independence and attendance compared to traditional classrooms. Students using PBL understand the content on a deeper level, retain content longer, and perform as well or better on high-stakes tests than students in traditional settings. Partnership with students. If we communicate the message that a valued student is one who is quiet and compliant, we deny students the opportunity to be fully engaged, self-directed learners who take ownership of their academic growth. But, when students are given opportunities to co-construct their learning environment and learning activities, research has found students have better relationships with their teachers and peers, improved feelings of competence and positive self-regard, and are overall, more engaged, which ultimately, leads to improved academic performance. What do I do now? Consider the policies you can influence given your role in your school. For teachers, that will likely be the pedagogical policies. Take stock of your own policies. What could be adjusted to be more equitable? Once you’ve identified your area for growth, determine what you might want to learn more about this summer to prepare to implement your updated policy in the fall. Ask your school or district leaders about related PD opportunities. Check out educational podcasts, books, and blogs that discuss these topics. Next month, I’ll be holding free 1-hour online masterclasses that address the pedagogical shifts discussed in this post. If you are a school leader, consider providing summer PD opportunities or resource recommendations for teachers to do some asynchronous self-paced learning on these topics. If you still have time left in the school year, consider discussing these shifts before summer break. You may want to let the ideas of these big shifts come up organically. For example, ask teachers to identify what has been challenging this year and also identify moments of success. Then, have teachers notice themes of success and how they may connect to themes of challenges raised. As you facilitate, you could highlight emerging themes that connect to the research. That could look like:

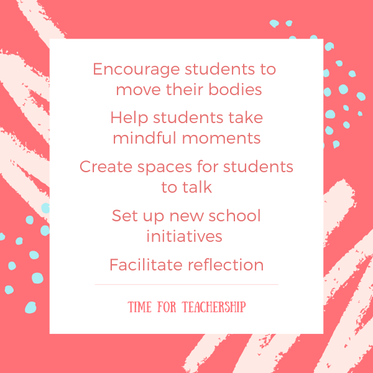

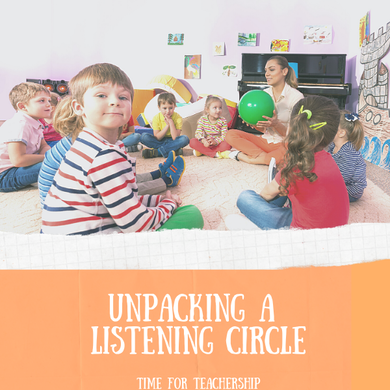

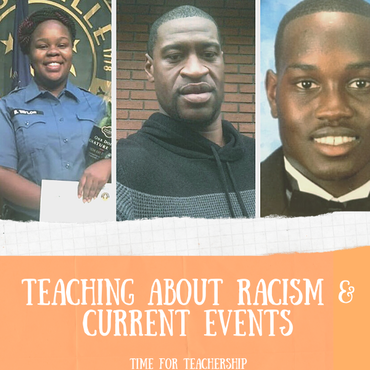

Note: If you are in a leadership role, leading a staff PD or PLC meeting, this activity can be part of the meeting, but you could also informally suggest this activity to colleagues by sharing that you tried it and found it helpful to prepare for fall. If your colleagues or supervisors need a quick summary of the research and the instructional pivots to close the opportunity gap, I made a one-pager for you. Many students are experiencing high anxiety without the usual relational supports like seeing teachers and peers in person. Many students have been impacted by death this year—from disease and racist violence— and the resulting fear for their own safety and the safety of family members can be overwhelming. There is much to do to resolve these larger issues of systemic racism and a pandemic, but let's think about how we can support students to manage their anxiety in the moment. As a teacher, sometimes I forgot to teach coping strategies as part of a lesson, but it’s important to do so. Not all students have coping strategies, or they may have coping strategies that are unhealthy or ineffective. So, it’s up to us to explicitly teach students a variety of strategies they could use to cope with stress, thus enabling each student to make an informed choice about what works best for them. Encourage students to move their bodies. Research has shown that physical activity can reduce anxiety and depression. Some students may have physical limitations on how they are able to move their bodies, so provide a range of options here. If students have a phone, they can track their steps over the course of a day or a week. They can exercise by running, doing bodyweight activities like squats or pushups, or following along with an online fitness video. Help students take mindful moments. Some students may want to use a simple strategy like breathing deeply for 60 seconds. Others may need more structure. Here are some options you could offer: Suggest a breathing strategy like smell the flower (inhale), and blow the bubbles (exhale) or balloon breathing (lifting arms over the head on an inhale to “blow up the balloon” and bringing arms back down on an exhale to “deflate the balloon”). Tell students about guided meditation sites like Stop Think Breathe (there’s one for older students and one for younger students), Calm, or GoNoodle (this one’s typically for young students). To help bring mind and body back into the moment, take a minute to experience each sense. One at a time, focus your attention on your sense of sight (e.g., identify 5 objects in your space), then sound (e.g., notice what you hear around you), then touch (e.g., touch 2-3 different textures around you), then smell (e.g., notice what you smell), and finally, taste (e.g., if you are eating or drinking). Create spaces for students to talk. If you have the time and emotional capacity for this work, this space could be facilitated by you as the teacher. However, recognizing that emotional labor takes its toll on the facilitator, you may also want to suggest other places for students to go. This might be a school-based resource like counseling, or an anonymous online space like ADAA’s online support group. Set up new school initiatives. How could we think outside the box to dream up innovative ways to support students’ mental health moving forward. Is it possible to partner with a local organization to offer animal therapy at your school? Is it possible to designate a room as a mental health break room where students can take some deep breaths or even a quick nap? Could you help students start a club to raise awareness of youth mental health? Facilitate reflection. You may want to set up a reflection space (either private or public to other students) for students to record how they felt before the activity, what strategy they tried, and how they felt afterwards. This way, students can identify trends to increase their own awareness of their bodies and moods. If you set up a community space for your class to share these insights publicly, some students may benefit from the additional accountability and/or learning from their peers’ strategy uses or “aha” moments. Taking time to teach these practices and help students identify the ones that work best for them is investing in students’ lifelong abilities to be more present and resilient. This is especially helpful for students who have experienced trauma, which research tells us, is the case for most of our students. Earlier this week, I mentioned Morningside Center, a restorative practices organization in NYC, which creates community circles for teachers that are responsive to current events. Since I published that post, Morningside Center put this circle up on their website. Educators can use the listening circle to facilitate class discussions of the police killing of George Floyd. Inside the resource, there are several options for how to open the circle, questions to ask during the listening portion of the circle, and several options for quotes to close the circle. Read through the options, and choose what feels right for your students. In addition to sharing the circle lesson itself, I also want to share some additional things to consider as you prepare to have (or continue to have) conversations about racism and police brutality in your classes. Process as a staff. If you are an administrator or teacher leader, facilitate a staff circle so educators can discuss police brutality with their colleagues. You could even do the same listening circle with staff that you do with students. There are a few reasons for this. One, staff members may benefit from processing their own emotions and being able to listen to others. (Read the section below to ensure you are mindful of how Black educators’ needs will differ from educators who are not Black.) Second, teachers may be better equipped to facilitate conversations with students once they’ve talked as a staff—it may prepare teachers for specific ideas that may be shared (and how to respond), and it may be helpful for teachers who have not facilitated a circle before, to see circle practice modeled and experience circle participation first-hand. Consider the different needs of your students. If you have both Black and non-Black students in your class, be mindful of how Black students would like to participate. Black students do not need to carry the additional emotional weight of their white peers or act as spokespeople for the Black community. Don’t force students to participate in a way that is uncomfortable, and offer Black students a separate space to talk with one another if desired. If you have a class of all Black students and you are a white teacher, be mindful of that. Recognize your privilege, listen, and make a commitment to anti-racism by stating what action you will take to address system racism in your community. If your class is all white, bring in Black voices (either live, if someone has expressed a desire to talk to your class, or by selecting an existing video, article/text, or social media posts). Help your students recognize their white privilege and provide them with examples of white allyship and anti-racist activism. Remind students of your community agreements. Likely, you set agreements or “norms” at the start of the year. You may have revised or rewritten then during distance learning. Remind students of them before you start. You may need to update them again before you begin. It’s important to establish an anti-bias class culture that is conducive to listening and values empathy before you start discussing any difficult topic. Facilitate with intention. As the circle keeper (facilitator), you are not speaking very much. You honor the talking piece, and only speak when you have it, like all other members of the circle. However, you will speak at the start to frame the conversation, and at that point, you may want to define important terms (e.g., systemic racism, police brutality, white supremacy, white privilege). You will also want to frame the current event as one moment in a long history of racist oppression. It’s important to contextualize the conversation and highlight that this is not an isolated incident. Finally, consider using your final circle question to help students, particularly white students, identify an action they can take to be better allies to the Black community. You may want to do some research beforehand, and read what Black activists recommend white allies do, so you can offer some examples and also model with your own response (if you are a white teacher). Adapt for distance learning. Circles may be slightly more challenging to facilitate on Zoom or Google Meet, but they are still possible. I’ve found it logistically easiest for the facilitator to read off students’ names (either from a class list or in order of how they entered the room) so that everyone knows where the virtual “talking piece” is. Then, the students can unmute and respond by answering the prompt question or saying “pass.” If you want to use the Morningside Center circle as a jumping off point or create your own circle from scratch, I’ll reshare my simplified circle template below. Just make a copy, and add in your own content. If you feel comfortable, you can share the finished product in the comments section of this post or in our Time for Teachership Facebook group to support other educators in anti-racist work. To be clear, I, as a white female educator, am in no way claiming I know how to do this work perfectly. I’ve facilitated conversations about racism and oppression with students for 7 years, and I still have a lot to learn. I’m sure there are things to add or adjust here, so please, let me know what else educators should consider as they implement circle discussions. The killings of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd are just the latest in a long history of racist violence in the United States. As teachers, we may feel uncertain as to how to address these events in our classrooms or unprepared to have conversations about race with our students. But, we have to have these conversations. We have to talk about racism. Educators and non-educators alike have told me throughout my teaching career to keep my curriculum “neutral,” but there is no such thing as neutral content. Silence reflects an acceptance of the status quo. As Jamilah Pitts, writing for Teaching Tolerance says, “Students pay attention to everything we say and do. They particularly pay attention to our silence.” Black children need to know their teachers believe their lives matter, that their teachers see their humanity and will speak out against actions that violate that humanity. Children who are not Black need to see compassion, courageous conversations, and anti-racist activism modeled by their teachers if they want to be able to do these things themselves. So, where do we start? Self Assess. If this is unfamiliar territory to you, start by self-assessing where you are on this cultural proficiency continuum or take a look at various theorists’ stages of racial identity development. Identifying where you are in these progressions can be a start. It shows you a path forward and may highlight some ideas or practices that you may not have previously thought about. Learn More. Educators who seek to learn about the problem of racism will be more likely to highlight racism when it happens and be more prepared to thoughtfully respond to racism in the moment. There are many amazing resources out there. Books I’ve found helpful include: Understanding EveryDay Racism by Philomena Essed, The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander, and Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?, by Beverly Daniel Tatum. There are so many more. For white educators, be an ally. White educators, we need to recognize our white privilege. A short, but powerful article I continue to use in my teaching practice is “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” by Peggy McIntosh. Also, we need to push past our discomfort in talking about race in order to be better allies to the Black community. The book White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo does a great job of breaking this down, and this podcast episode provides a great summary if you don’t have access to the book. As a white woman, I struggle with the fear of being labeled “racist,” and I am continuously working to overcome this fear that inhibits me from engaging in uncomfortable, but necessary conversations. I’ve found Jay Smooth’s dental cleaning metaphor to be helpful in accepting that we are all steeped in racism. It’s not about “not being a racist,” it’s about accepting feedback and working to “clean your teeth” everyday to remove the racism that pervades our culture. Find resources to share with students. This “web package” of resources from Teaching Tolerance on teaching racism and police brutality is filled with ideas for your own learning and for student-facing content. Look through the resources and find something that fits for your context. This New York Times piece also includes links to texts and resources to help students start to think about race in your class. Invite conversation. While set up for an in-person class, this circle developed for teachers to discuss the shooting of Philando Castille with students provides a list of questions and concepts that are still relevant today. Morningside Center, the creators of this circle, often produce new circle lessons based on current events, so keep an eye out for new circles as well. [UPDATE: This is the circle Morningside Center developed in response to the police killing of George Floyd.] Let’s Talk from Teaching Tolerance is a 44-page guide you can read for free to support you in effectively facilitating difficult conversations with your students. For administrators and teacher leaders, it’s also helpful to create spaces for conversation among staff. Consider the difficulties of having tough conversations at a distance. The Teaching Hard History podcast (from Teaching Tolerance) recently shared an episode a few weeks ago about the difficulties of hard history with students while we are in a distance learning setting. The episode, “Hard History in Hard Times – Talking With Teachers,” shares many tips and resources that are also relevant for discussing racism in the context of current events. For one, you don’t need to share the traumatic videos. Lauren Mascareñaz writes, “Witnessing the seemingly constant horrors that are happening in our society is a call to action for many people, young and old. But we have to be aware of the potential effects of what we—and the children in our schools—are seeing.” For young students. Research has shown kids as young as 5 years old hold many of the racist attitudes adults in our culture hold, and they “associate some groups with higher status than others.” If we don’t interrupt these messages at a young age, students will continue to internalize the systemic racism that pervades U.S. culture. How you address racism with students may look different at age 5 than at age 15, but it should still be addressed. This post shares ideas for bringing Black Lives Matter into classes at various grade levels. I chose education as a profession because I thought (and still think) it’s one of the most powerful ways to address systemic racism, xenophobia, and gender bias. I’m certainly not perfect in how I facilitate conversations about race with my students, but I have a responsibility to try my best and commit to constantly improving my practice. Let’s all help each other do the same. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed