|

We often talk about self-care. Often the words of Black, lesbian feminist, Audre Lorde are invoked, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence. It is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare," (A Burst of Light). Certainly, it’s important to re-energize ourselves when we are worn out, but many feminists of color are reminding us to remember the last part Lorde’s quote. Taking care of one’s self is a political act. With this in mind, we can acknowledge that the notion of self-care has created a huge industry of expensive products and services, and only some people are able to afford these kinds of commodified self-care purchases. In response to this reality and as a way to keep Lorde’s original purpose in mind, many feminists argue we should practice “collective care” or “community care” as well as caring for ourselves. Nakita Valerio defines community care as, "People committed to leveraging their privilege to be there for one another in various ways.” She gives an example of picking up food or providing child care for people who are grieving (Mashable). Meg Leach’s explanation of community care as “building networks of people who can help when community members need it...making self-care possible for those who cannot achieve it on their own,” highlights the disparities in an individual’s capacity (financial or otherwise) to care for themselves. A benefit of community care is that, “members can benefit from the expertise of multiple people,” (The Tempest). At the National Women’s Studies Association Conference, women in academia provided examples of engaging in collective care work as scholars. Rather than simply seeking to advance their own number of publications and individual success, they supported one another’s research and used their personal connections to introduce each other to various people, creating new pathways for professional growth! I see the relevance for K-12 educators. Teachers have a history of hanging onto the curriculum we develop, not wanting to share it. Sometimes, this may come from a feeling of needing to compete with one another or a fear of being criticized for the quality of the work. Most of the time, though, I think it’s because we put so much work into creating original units or worksheets or whatever it is, that it just feels unfair that another teacher could just take it and use it without having to put in those tens, if not hundreds, of hours to figure it out themselves! I get it. I’ve created new curriculum for each of the 7 years I taught high school. I continue to do it at the college level. There are many times I thought, “I could make a bunch of money if I sold this on Teachers Pay Teachers,” but ultimately, I chose not to do that. Instead, I set up websites for other educators to be able to take and use anything I created. (Here is four years of my Gender Studies curriculum!) I do not fault anyone for selling their creations on TPT. Teachers just don’t make enough money. Eventually, I plan to sell online courses to educators, but up until that point, I want to provide as much free stuff as possible. I want to tell you why I choose to share most of my stuff for free... First, I can afford to do it. If I couldn’t pay the bills, you better believe I would be selling all of my stuff. Second, I love the collective care idea the scholars at the NWSA Conference talked about. When my resources can help other educators get a win, I see that as my win too. It’s certainly a win for the students in those educators’ classrooms. The third reason is a bit of a selfish one. If one teacher can take something I give away for free, and then share their adaptation of it, I learn from that! I get new ideas by offering up inspiration for others to take, remix, and inspire me back. That process, while it may not always happen, is educational gold. In the spirit of inspiring others, I encourage you to join the Time for Teachership Facebook group, and share how a free resource from this blog has led to a win for you! You can also tag me in a post on your favorite social media platform. I would love to see what you’ve been up to and how you’ve put your own spin on something I’ve shared. Let’s keep the inspiration flowing!

0 Comments

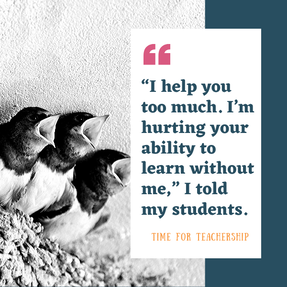

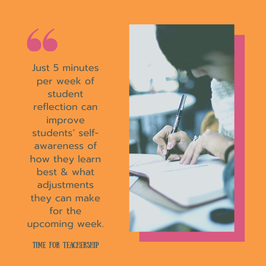

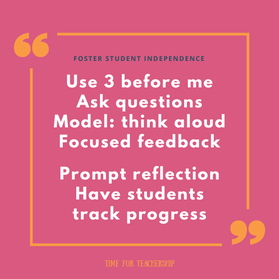

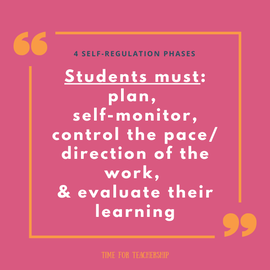

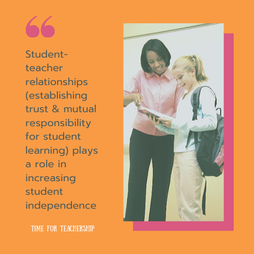

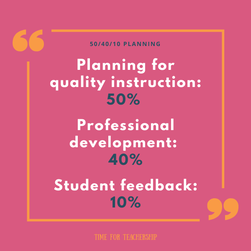

This blog post is the second of two related posts on student independence. I encourage you to go check out the first post before reading this one! It covers what student independence is (a process of self-regulation phases), why it’s important (it leads to improved student motivation and academic performance and is a requirement for the job market of the near future). When students can work independently, you are able to meet with students 1:1 or in small groups. They can speak to their learning processes and their progress on course-specific standards. Sounds great, right? In the previous post, I shared 4 tips on how to prepare for fostering student independence. This discussed planning differentiated lesson activities, being clear about the course/unit end goals, and consistently building relationships with students. While the preparation piece is critically important, this post focuses on strategies for teachers to implement during and after learning activities to foster students’ metacognitive thinking and help them take ownership of their learning. During a learning activity, teachers can: Use “3 before me”. This is one of the most important strategies I can recommend. As a teacher, I did not use it enough. I would rush over to help whenever students yelled, “Miss!” Finally, I made my teacher goal explicit to students. “I help you too much. I’m hurting your ability to learn without me,” I said. I made a large poster with a list of not 3, but 6 possible sources of information to go to when students had a question (before asking me). I put it up on the wall, and for the next week, we chorally recited the steps at the start of each class. To see how other teachers represent this strategy, google image search “3 before me”. There are tons of poster ideas. Follow a question with a question. When a student does make it to you with a question, ask them a question to help them generate an answer on their own. If it’s a feedback question, ask, “What do you think?” before you provide your own feedback. I also like, “What do you want me to focus on?” when students ask me to review writing drafts. It forces them to reflect on what they struggle with most, and it saves me time from pointing out all of the tiny errors that won’t be as high-leverage as one big topic like organization. When they are stuck, try asking, “What will help you most?” to prompt students to think metacognitively about how they learn best. This is a helpful first step to eventually getting them to seek out effective resources on their own. Model independent learning. Think alouds are great for this. Problem solve a practice problem in front of the class, and model what you are thinking and make explicit the steps you are taking to learn something new or complete a task. Provide focused & actionable feedback on students’ work. As I’ve talked about before, formative feedback has a big impact on student learning and saves you time grading student work after class. You can provide feedback on the specific task, but you can also provide feedback for students’ learning processes. Try to go beyond a generic, “You’re working hard,” which is certainly nice to hear, but a comment like, “I love that you chose to rewind the video and replay part of it so that you could answer the comprehension question,” can help students pinpoint what learning strategies as they are using and model for other students possible strategies to use. After a learning activity, teachers can: Ask students to reflect. Taking just 5 minutes per week for students to jot written journal reflections or record video journals can improve students’ self-awareness of how they learn best and what adjustments they can make for the upcoming week. Ask students to track their progress. In addition to reflecting on their learning process, you can also ask students to self-assess their progress towards the course standards they have been working towards. Students can also track their own formative and/or summative assessment data to monitor their progress. This can be done digitally (e.g., Google Sheets) or with crayons and paper. These don’t have to be publicly displayed, but could live in students’ data binders to keep it private. These strategies do not all need to be implemented right away. You can try out one at a time. The key is to make student independence one of the goals of your class. By doing this, you can address a lot of other struggles (e.g., off-task behavior, lack of motivation, students’ low academic performance). I’d love to hear what other strategies you have for fostering independence! Share in the comments, in our facebook group, or tag me on your preferred social media platform. Wouldn’t it be great if you had more time to meet with students 1:1 or in small groups? What if kids were more focused and excited about learning? What if students could lead conferences about their academic progress, not just sharing whether they behave or try hard, but really speak to the ways they learn best and their progress on each standard? It’s totally do-able. Fostering student independence is at the heart of all of these outcomes. What do you mean by student independence? Meyer et. al. note “the key ingredient in independent learning is the shift of responsibility for the learning process from the teacher to the student.” To do this, students need to understand how they learn, find motivation to learn, and collaborate with teachers to structure their learning environment. They discuss 4 phases of self-regulation which enable independent learning, so students must: plan, self-monitor, control the pace & direction of the work, and evaluate their learning (Meyer, Haywood, Sachdev, & Faraday, 2008). Why else should we foster student independence? Research has found student independence resulted in: improved academic performance; increased motivation and confidence; and greater student awareness of their limitations and their ability to manage them (Meyer et al., 2008). Student independence is also the first attribute of a portrait of a student who demonstrates “College and Career Readiness” (Common Core). The job market is shifting from what it was a decade ago. It is estimated that by 2020, 50% of workers will be independent contractors, and 85% of jobs that will exist in 2030 don’t exist yet ("The next era of human machine partnerships"). Students will need to be able to learn content and job-specific skills that we can’t teach them now because we don’t know what jobs they will be doing. We can, however, prepare them to be excellent independent learners. Then, they can learn anything they’ll need to know! Sounds great. How can I foster student independence? As students will go through different phases of self-regulation, teachers can do different things to support students depending on what phase of the learning process they are in. This post focuses on what to do before a learning activity. Next week, I'll share another post focused on support student independence during and after a learning activity. Before a learning activity, teachers can: Clarify the end goal for students. Answer the question: What’s the purpose of this class? (Don't let the answer be just “to get to the next grade level”.) What skills are students learning that will serve them throughout their lifelong educational journeys? I talk more about teaching standards and share free rubric rubric templates for skills-based grading in an earlier post. Prepare differentiated learning experiences. Each student should be able to experience success and an appropriate challenge. This takes some resource gathering, but the lesson activity itself can remain the same for all lessons. Choose a protocol that works for you and your students and re-use it as you teach and learn new content. (Some of my favorites: jigsaw or workshop (for differentiated groups) and What I Need a.k.a. “WIN” Time (for independent work). Want to see it in action? Watch this video from BetterLesson, highlighting the latter strategy inside “Master Teacher,” Daniel Guerrero’s classroom. Offer student choice. Provide opportunities for students to determine how they want to learn new information, what they want to learn (have students set a goal!), or how they will demonstrate their learning once they’ve achieved mastery. Choice increases students’ intrinsic motivation, effort, task performance, and retention. If students do not find the information interesting or important, their working memories will not process it and they won’t remember it (Marzano, Pickering, & Heflebower, 2010). The more we can offer choice to students in choosing the learning experience that's most interesting to them, the more they will learn! Build relationships with students. This may sound strange in this list, but research has found student-teacher relationships (specifically, the establishment of trust & mutual responsibility for student learning) plays a role in increasing student independence (Meyer et al., 2008). Marzano, Pickering & Heflebower agree relationships are important. They note, “the most general influence on a student’s emotional engagement is a teacher’s positive demeanor,” meaning their enthusiasm for learning as well as their ability to help students feel, “welcomed, accepted, and supported,” (2010). Planning for instruction is obviously a huge part of what we already do as teachers, but keeping the student independence goal in mind as we plan can help us make important decisions that deeply impact student learning in the long run. Start by trying just one tip. Remember, helping students become independent learners can address a lot of other struggles (e.g., off-task behavior, lack of motivation, students’ low academic performance). I’d love to hear how you plan for student independence! Share in the comments, in our facebook group, or tag me on your preferred social media platform. It wasn’t until I left the classroom to become a coach that I was able to look back on my practice and deeply reflect on how my planning process changed over the course of my teaching career. I knew my first few years of teaching, my planning process—regardless of the things outside of my control like being a new teacher and having an unreasonable schedule—was a lot more stressful than my process in the second half of my teaching career. Looking back, I realize this shift was marked by two things—professional support (including quality professional development that exposed me to different ways of teaching and an administrator who encouraged us to live life during our non-working hours) and my ability to get serious about setting boundaries (committing to spending less time and eventually no time doing work at home). As I pulled together all of the specific professional development I’ve received and reflect on when I was truly at my best as a teacher (the students were most engaged and I was most energized), I realized the way I spent my non-teaching time fell into three categories: planning for quality instruction, professional development, and providing student feedback. Most teachers do these three things. This isn’t new, but what may be shocking is the percentage of time I was spending on each one. Here, it is, my 50/40/10 planning approach...

Take a moment for that to sink in. Experience all of the “This is why this will never work for me” thoughts. Then, take a deep breath and let yourself entertain the idea—if only for the rest of this post. Before we continue, if you haven’t downloaded my 50/40/10 planning bundle (updated in November to include tracker templates and activity resource banks), get it now! Let me directly address some of the hesitation that might be happening in your minds right now: I could never spend that much time on professional development. I would never finish my work! What if the professional development you spent time on taught you how to plan efficiently and grade faster and it actually saved you time in the long run? What if it helped you build engaging learning activities so that students were on-task and excited to learn every day? What if it meant you would be able to stop taking work home—the planning/grading work and the mental stress? Unfortunately, many teachers’ experiences of professional development is not helpful to their practice. It often means sitting in a staff workshop and listening to someone talk about something that may or may not have an impact on the quality of your instruction. That’s not the kind of PD I’m talking about. I’m talking about visiting a colleague’s class to see a particular strategy in action, collaboratively brainstorming an upcoming lesson idea, listening to podcasts, reading textbooks or blog posts on education specifically or another relevant topic like working efficiently, work-life balance, content you’re preparing to teach. I’m starting to curate a list of free, online resources on my “Professional Growth” Pinterest board. Check it out when you’re looking for something new to learn, or go back and read through any of the posts on this site! Also, I counted any PD offered by the school as part of my 40% professional development time. Remember, this is how you spend your non-teaching time, not your prep period specifically. This could also be grade, department, or PLC meetings. Once or twice a year, I signed up to visit another school to see what else was possible. I count this as a full day of PD in my 50/40/10 approach! Once a year, usually in the spring, the department was given one full day for curriculum development. This happened in 2 of the 3 schools I have worked, and it was a game-changer. Wait, wait, wait...you’re suggesting I leave my class for a day? I can’t do that to my kids! I want to start by saying you are a caring teacher who clearly loves your students. Now, I want to push you a little bit and ask: what if the thing you could accomplish by missing ONE day of class could drastically improve student engagement and achievement? This is truly a mindset game. I know what happens on days when you have a sub—nothing. It is a rare class that has their routines and intrinsic motivation so together they can function when the teacher is out. So, let’s play this out…Let’s say they learn absolutely nothing the day you are out. Not great. But, what if you come back energized and equipped with several ideas that will help those kiddos be enaged the rest of the year? Is that not worth it? Would you be willing to sacrifice one day of learning and the time it takes to prep sub plans (which, yes, is usually harder than being there yourself) if it meant you and your students were energized and engaged for the rest of the year? What if it just increased engagement for semester? One unit? Even if things are currently going well, ask yourselves if you believe they could be better. And while you’re thinking this through, keep the kids at the heart of this decision. It’s their learning we’re talking about. Your initial reaction may have been, “I can’t leave my kids. They’ll miss out on a day of learning.” That may happen, but are you willing to risk the students missing out on deeper, more engaged learning opportunities they could have if you went? This sounds great if PD was actually good. I don’t have access to good PD. Advocate for these opportunities. Most of the 100+ administrators I’ve worked with would be absolutely thrilled for teachers to ask to go visit another school or request PD on a specific topic. Honestly, just ask. If you’re nervous about asking, get a few other interested teachers and ask together. Grading takes way more than 10% of my time. Providing feedback to students is very important, but grading a piece of student work is just one of the ways to provide students feedback. Formative feedback is a way to provide students feedback in a way that saves you time and is more impactful for student learning! In Hattie’s book, Visible Learning for Teachers, he describes the research on formative assessment. The Main Idea summarizes, “One researcher compared rapid formative assessment to 22 other approaches to learning and found it to be the most cost effective – this is in comparison to approaches such as a longer school day, more rigorous math classes, class size reduction, a 10 percent increase in per pupil expenditure, an additional school year, and many other approaches. Rapid formative assessment, as it is being defined, is when short-cycle formative assessments occur during the lesson to provide feedback to teachers and students to help them make decisions. “Should I relearn…Practice again…Move forward?” These “in-the-moment” assessments provide immediate feedback during the process of learning. There is a lot of evidence that when these formative assessment practices are woven into the minute-by-minute classroom activities of teachers, there can be a 70 to 80 percent increase in the speed of student learning,” (p. 8). Taking time during the lesson to provide feedback may require a re-structuring of your class activities. You may need to digitize your exit slips or quizzes to be auto-graded. You may want to organize independent work time so that you can meet with students 1:1 or in small groups to provide immediate feedback. This may be a hassle, departing from the way you currently operate, but it will save you time grading and it can drastically improve student learning. So, switching to more formative assessment is more beneficial and efficient for everyone involved. Sure, you’ll still need to provide feedback on summative assessments occasionally, and for that, tech can offer some support. I wrote a post about time saving tips that features a section on grading, so check that out for more tips and specific tech tool suggestions. We could talk all day about this approach, so I’ll wrap up this post here, and prepare myself for questions. Add questions or share successes you’ve had with the approach in the comments below or on our private facebook group. I’m excited about the transformative power of this approach to planning, and I can’t wait to continue supporting you on this journey! Content is important! But, how students access content is going to impact how deeply they understand and contextualize it. The internet has changed students’ ability to access information, immediately. They will have the ability to do this as they go through life. If their job requires them to know a particular math formula, they can Google it. They can even find a YouTube video that teaches them how to use it. If students can Google a fact, they don’t need us to give it to them. What they will need is someone to teach them how to Google effectively, how to sift through information, determine what’s credible and relevant to the question they want to answer, how to ask the right questions from the start, and how to synthesize the information and apply it to a novel problem. They will need someone to teach them how to persevere when they get stuck, understand how they learn best, and identify what motivates them to learn more. They will need someone to re-teach or re-frame the content when they are struggling or to push them to go further when their application is mediocre and they could do better. I want to be clear: I am not saying content is irrelevant. Nor am I suggesting there are never times when you provide Google-able information in a lecture-style format. Content and (short, interactive) lectures certainly have value. What I am suggesting is to get out of the mindset that we need to race to cover a massive amount of content in one school year and instead, think about the handful of skills we want students to master in that one school year. From there, you can determine the key foundational concepts students must learn. It’s easier to plan this way because you won’t forget to build in content (you need it to contextualize the skill-building). However, it is easy to forget to build in the skills when using a content-first approach to planning. How is this better for students? The research highlights the importance of helping students become better learners. Teaching students how to integrate new content with existing knowledge has a .93 effect size on student learning, and teaching students how to transfer strategies across subject areas and activities has a .86 effect size (Hattie, 2018).. Helping students develop independent learning skills is one of the best things you can do for them! Furthermore, independent learning skills are critical for students’ success in their jobs and in their lives. It’s estimated that in 2020, only a month away, 50% of workers will be independent contractors and by 2030, 85% of the jobs that will exist have not yet been invented ("The Next Era of Human Machine Partnerships"). If students don’t know how to process new information and learn on the fly, they will likely not be able to survive economically. The job market is rapidly shifting, and we may need to make some adjustments to our way of teaching in order to prepare students to be successful in it. What could this even look like? New ELA curriculum from EL Education, which has already demonstrated its impact on student learning, provides a fantastic example of a curriculum focused on skills and going deep with less content. They have just four units per year, and they spend a lot of time building independent learning skills, habits of character, and deep content knowledge within the four selected topics. Additionally, the New York Performance Standards Consortium has an amazing track record of success with skills-based instruction and assessment. Here are the skill-based rubrics they use for each of the core subjects. Each subject’s rubric is used to assess every unit assignment from 9th-12th grade, and is just slightly scaffolded based on grade level expectations. Planning like this requires a shift in the question(s) you ask yourself. Instead of “What content will I cover today?” ask, “What will students do today?” How could I get started? This may be a drastic departure from your existing curriculum planning process. If it’s a big shift, you don’t need to make it all at once. Here are some options to get started...

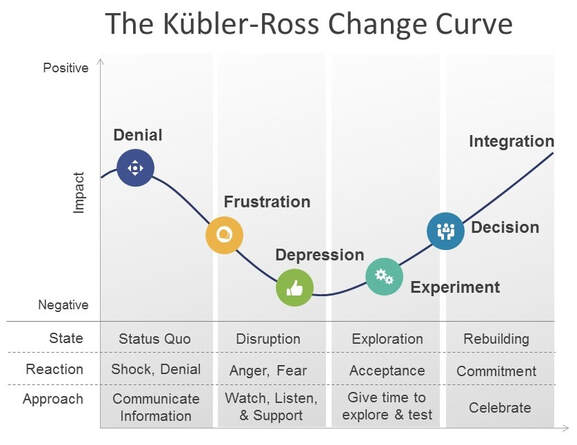

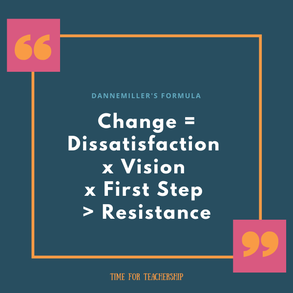

Both of these approaches requires you to select a skill(s) and determine what mastery of that skill will look like. To help you out, here are two skill-based rubric templates. For the mastery-based rubric, I used a bike analogy to head each category (mastery level), but I’ve seen people use other creative analogies such as baking, Star Wars characters, and other subject-specific examples. Be as creative as you want. Have fun with it! I can’t wait to see your rubrics and hear how prioritizing independent learning and application skills over Google-able facts helps you with your planning. Once you give it a try, I want to hear from you. What roadblocks got in the way? What successes did you have? What questions are you grappling with? Post your questions or share your successes with the Time for Teachership facebook group. Asking questions in the group taps into the power of collective problem-solving, and when you share your wins, it inspires others to see what’s possible! Remember, real change takes time. Continue to think big, act brave, and be your best self. The results will come. Principals, assistant principals, instructional coaches, school leaders, have you ever had an exciting idea that you just know will be so good for teachers and students, but the biggest barrier is a lack of buy-in from teachers? The phrase, “but this is how I’ve always done it,” may have become your greatest nemesis, right along with “I don’t have time for this.” Getting buy-in to a new initiative is hard work. In this post, I share 4 research-based strategies school leaders can use to effectively lead change. The first few suggestions may sound familiar. I’ll repeat them over and over because they are critical to successful change management. Have one clear vision. Choose 1-2 goals for the year (or more years—3 to 5 years is ideal for major initiatives). Research on Massachusetts turnaround schools found the schools who did not make gains lacked prioritization of a couple key areas, instead focusing on too many things at once (DESE). These 1-2 goals should be data-informed, high-leverage, and co-created with stakeholders or a representative stakeholder team. Manderschild & Kusy (2005) write about vision, citing Kouzes and Posner’s finding that a clear vision leads to “higher levels of [employee] motivation, commitment, loyalty, esprit de corps, and clarity about the organization’s values, pride, and productivity,” (p. 67). They also note it is important to measure progress towards the vision within performance evaluations. If it’s a priority, make sure your feedback to teachers and evaluation of their growth reflects that priority. Make space on teachers’ plates. We can’t add to teachers’ plates without taking something off. If it’s a priority, something else can go. I talk more about this in my post on how to support teacher leadership, where I share a free quick guide on how to carve out time in the school day for teachers to grow, learn, collaborate, and invest time in new initiatives. Next Tuesday, I’ll share a teacher-facing blog post to support teachers in re-thinking how they spend planning time to make space for individualized professional development. If it’s helpful, check it out and send it to teachers to help them make that shift. Connect with teachers’ hearts. The prominent adaptive leadership scholar, Ronald Heifetz, says, “What people resist is not change per se, but loss,” (Heifetz, Grashow, & Linsky, 2009). Teachers’ identities are tied up with their jobs. With the role of teachers shifting from “sage on the stage” to “guide on the side,” it’s reasonable to expect there may be a bit of a loss of identity. Ultimately, we want to help teachers see the value of this shift—that students benefit more when we teach them how to be learners not simply what to learn. However, immediately after introducing this shift, it’s important to empathize with and speak to that teacher identity and sense of loss. Use that to paint a picture of how the new initiative or vision speaks to their passion for student learning (because, if it’s a good initiative, it definitely will). If teachers don’t seem ready for a change, Anderson (2012) says, talk (and listen) to them, share the data to let them discover the issue and urgency themselves, and share research on the topic to lend credibility to what you’re trying to do. Just don’t forget the heart! Kotter & Cohen (2002) warn that many change initiatives fail because they rely too much on the data end of things instead of inspiring creativity by harnessing the “feelings that motivate useful action” (p. 8). The image of the Kübler-Ross change curve below may help you recognize where teachers are, emotionally, during the change process and how you can support them during each stage. Create dissatisfaction with the status quo. I love Dannemiller’s adaptation of Gleicher’s formula: change = dissatisfaction x vision x first step > resistance. This formula accepts that resistance happens, but it can be overcome as long as teachers can recognize their dissatisfaction with the way things are now, there is a clear vision for how this can change, and there are acceptable first steps we can take. These variables are multiplied, meaning if any one of them doesn’t exist, resistance will win (because any number multiplied by 0 is 0). If there is no dissatisfaction, leaders must create it! Mezirow (1990) notes adults need a disorienting dilemma to jumpstart transformative learning (learning that requires a paradigm shift and asks us to critically examine our assumptions rather than just learn a new skill). A disorienting dilemma forces us to examine our assumptions. Presenting teachers with information that makes teachers just uncomfortable enough to realize, “the way I’ve been thinking about this isn’t working anymore,” will help them try on other ways of thinking and be willing to rearrange how they see the world. This is most effective in the context of group dialogue, as folks are able to briefly “try on” others’ ways of thinking. So, go ahead and create a disorienting dilemma! Also, remember that major transformation is usually made up of a lot of little changes over time. You won’t shift mindsets in one meeting, but you can present the disorienting dilemma and let the disorientation start to sink in. When teachers are sufficiently disoriented, they will be seeking new ways of thinking, and you’ll have an opportunity to introduce those new ideas. To think about possible disorienting dilemmas for teachers, consider presenting a situation in which two values that teachers hold are in direct competition. For example: A teacher finds themselves working 60 hours each week to complete lesson plans and grade student work. This positions their personal well-being in direct conflict with their love for student learning. Let teachers recognize the discontent, explore the underlying assumptions, come to the conclusion that transformational change is the way to overcome the discontent, and start exploring different ways of thinking that could address this dilemma. Once teachers get here, you can take them through the final steps of making an action plan, testing it out, building capacity for this new approach (through PD, coaching, and other support), and integrating this practice into teachers’ lives and ways of being. (The summary, “Mezirow’s Ten Phases of Transformative Learning” has a bit more detail on the transformative process.) Change is difficult, and it takes time. These research-based ideas will get you started, but the real work is in how you bring teachers into the change process. Help me create resources that address your challenges with leading change! I would love to hear what challenges you’re facing and what kinds of change initiatives you are working on in your schools. Share any questions or success stories in the comments below, in our private facebook group, or by hitting reply to my latest email. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed