|

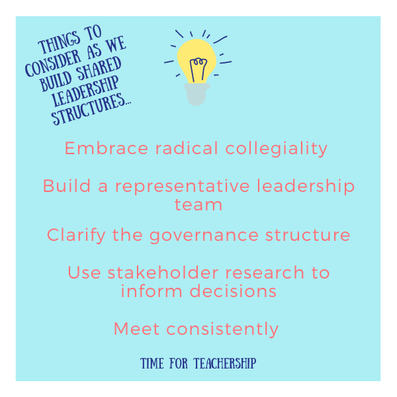

Our sharpened focus on issues of equity in education in the time of COVID-19, has raised many questions such as: How can we improve educational equity? What policies are perpetuating inequity? How can we replace them with policies that promote equity? How can we systematize equitable practices so they are not “one-time” strategies? How can we measure this? (In other words, how will we know if we are successful?) And with all the things that are uncertain, leaders are asking: What is within my locus of control? As a leadership scholar, my response to each of these questions is: shared leadership. I prefer this term to the more popular, “distributed leadership” because while distributed leadership is inclusive of teachers in leadership, it stops short of sharing leadership with students and parents. Shared leadership enables us to be inclusive of all stakeholder groups. Additionally, the word “shared” is centered on what Mary Parker Follet calls “power with,” whereas “distributed” maintains a hierarchical sense of “power over.” How can we improve educational equity? We cannot answer the question of how to improve equity by ourselves. I can suggest some places to start, but to address the needs of your specific community, you’ll need to ask the various stakeholders in your community. Shared leadership asks us to listen more than we talk. So, the first step in identifying how your school can improve equity is identifying who can provide answers. That list will include families and caretakers, students, teachers, and perhaps members of the larger community. What policies are perpetuating inequity? Encouraged by this year’s renewed societal commitment to eliminate institutional racism, educators have been increasingly focused on identifying and dismantling the policies that perpetuate educational inequity. Many schools are starting to take a hard look at punitive discipline policies, problematic dress codes, and how students are graded. However, even if we can identify policies that need to be changed, we need to include stakeholders in the creation of whatever policies replace the old ones. How can we replace inequitable policies with policies that promote equity? Research tells us organizations benefit from improved decision-making when multiple stakeholders are involved in the decision-making process (Kusy & McBain, 2000). If we want to be more equitable, we need the students and families who have been historically marginalized by inequitable policies at the policy-making table. The policies are important, but how they are created and whose voices are involved in the creation process is how we ensure new policies don’t continue to perpetuate inequity. How can we systematize equitable practices so they are not “one-time” strategies? Creating shared leadership structures that inform the school’s decision-making process is a powerful way to systematize the school’s commitment to equity. If each time a policy is created, parents, students and teachers are part of the process, this communicates to stakeholders their voices are truly valued. Furthermore, given all the uncertainty of this school year, how decisions are made is one thing that is within a leader’s locus control. The decision to share power is a powerful step towards educational equity. Logistically, researchers have identified several things to consider when creating shared leadership structures: Embrace radical collegiality. Fielding (2001) defined this term in relation to students, but it’s useful for our work with families and caretakers as well. Basically, it refers to the idea that educators learn and become more effective when they see students (and families) as partners and they share responsibility for student success. This mindset is critical to the success of any organization rooted in shared leadership. Build a representative leadership team. Research has found groups larger than about 15 members can become unwieldy and ineffective (Calvert, 2004; Pautsch, 2010). As much as possible, stakeholders should be represented equally, with a slightly higher percentage of students to reduce the ratio of adults to students, which has been known to overwhelm and thus, silence students (Osberg, Pope, & Galloway, 2006). Clarify the governance structure. Explicitly state how and to what extent power is shared. Identify which types of decisions will be made solely by the school’s administrator(s), and which types of decisions will be shared. Clarify what is needed to move forward with a decision (e.g., majority vote, unanimous agreement). Determine leadership team members’ responsibility to communicate with the stakeholders they represent (e.g., weekly, only to get feedback on major policies). For example, the leadership team may draft a new policy and want to get feedback within one week from all stakeholder groups so they can vote to approve the policy the following week. Use stakeholder research to inform decisions. Decisions made by the shared leadership team should be based on data. To address the question of how we measure equity—sometimes, we will look at student data like grades or test scores. Other times, that data will be survey data in which stakeholders share their degree of belonging in the school or the extent to which they feel their voice is valued. Students may self-report their level of engagement in class. Members of the leadership team should receive the support needed to enable them to communicate regularly with the stakeholders they represent. This could take the form of tech tool training so all members are able to create and send out a survey using Google Forms or to communicate asynchronously using an app like Voxer or an LMS like Google Classroom. Meet consistently. Meetings should be held consistently, at the same time and in the same place (whether that’s the same physical location or the same virtual room) if possible, to avoid confusion that may exclude members from participation in the meeting. To help you get started in thinking through all of these considerations, I made a worksheet with a list of relevant questions. You can use it to guide your thinking as a leader or prompt discussion among stakeholders or in your leadership team! Two leaders who have informed my coaching and leadership practice are Ella Baker and Mary Parker Follet. Ella Baker, a staunch supporter of shared leadership during the U.S. civil rights movement has said, "I have always thought that what is needed is the development of people who are interested not in being leaders as much as in developing leadership in others." Follet (1924) addressed leaders’ fears that power was a zero sum game, by writing, “first, by pooling power we are not giving it up; and secondly, the power produced by relationship is a qualitative, not a quantitative thing” (p. 191). She later wrote that sharing power is generative, that confronting and integrating different ideas “means a freeing for both sides and increased total power or increased capacity in the world” (pp. 301–302). I’m excited to hear how your shifts towards shared leadership increase capacity and equity in your schools.

1 Comment

Lejla

11/15/2020 01:54:41 pm

The true mark of a leader is their ability to build leadership capacity in others. I love this entire post. Right on, Linds!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed