|

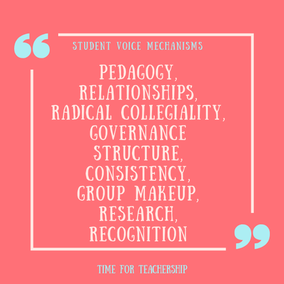

In a previous post, I highlighted research demonstrating the value of student voice, and specifically, student leadership, for individual student growth and for the growth of the school. This post focuses on how schools can measure students’ perceptions of the available leadership opportunities in their schools. I have developed and validated a measurement tool for schools to assess the presence, or perceived presence, of student leadership opportunities, and at the bottom of this post, I share it with you as a ready-to-use Google Form completely for free! Before I share the link with you, I’ll explain exactly what it measures. 3 Levels of Capacity-Building The three main sections of the form are based on Mitchell & Sackney’s (2011) three dimensions of capacity building, which include: personal capacity building, defined as building individual student skills; interpersonal capacity building, defined as students working with teachers to make school decisions; and organizational capacity building, defined as involving the school culture, structures, and ways of communicating. 8 Voice-Fostering Mechanisms After synthesizing the existing research on student voice, I identified 8 mechanisms (specific practices or structures) that scholars have identified as having the potential to improve the success of student voice initiatives in schools. I organize these within under the umbrellas of the 3 levels of capacity-building. Personal capacity building includes the pedagogy mechanism, or how information is conveyed and made accessible to all students. Interpersonal capacity building contains the mechanisms of relationship building between youth and adults as well as radical collegiality, defined as “an expectation that teacher learning is both enabled and enhanced by dialogic encounters with their students in which the interdependent nature of teaching and learning and the shared responsibility for its success is made explicit” (Fielding, 2001, p. 130). Basically, working in partnership with students and being willing to learn from them. Organizational capacity building includes the mechanisms of: governance structure (a school’s formal system of decision-making and where students fit into it); consistency (holding meetings at the same time and place); group makeup (smaller groups with an even youth:adult ratio are best); research (and it’s role in informing decision-making, often through participatory action research); and recognition (acknowledging and compensating students for their leadership work). 3 Leadership Competencies When we talk about student leadership, we often use the term generically, but there is a ton of relevant literature from the adult leadership world (and some emerging student leadership scholarship) that can help us address the often un-asked question: What kind of leadership? The survey I’m sharing with you measures 3 leadership skills or competencies: critical awareness, inclusivity, and positivity, which stem from authentic, social justice, inclusive, and positive leadership theories. Critical awareness is the skill of reflecting on, understanding, and questioning positive and negative attributes of one’s self and society in order to foster equity and growth. (informed by Preskill & Brookfield’s 2009 and Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing, & Peterson, 2008.) Inclusivity is the skill of enabling all members to fully participate and learn from each other (adapted from Booysen’s 2013 definition). Positivity is the skill of applying a strengths-based lens to facilitate growth and enable flourishing (based on Cameron’s 2012 principles of positive leadership). For more details on the research behind the validated survey, you can read the original dissertation study here or look for the much shorter, forthcoming journal article being published in AERA Open. How do I use the survey? Get free access to the survey by clicking the button below. Once you’re in, you’ll have access to a Google Drive folder that will enable you to right click on the survey file and “Make a Copy” for yourself. From there, this is yours! You can edit the introduction so it reflects your school’s context, purpose, and spirit. Double-check the setting to make sure it will NOT collect student emails. (We want it to be anonymous!) Then, share the link with students to complete. After you have collected the data, consider setting up a meeting with adult and youth stakeholders to discuss the trends and brainstorm possible next steps. You may also want to hold single stakeholder focus groups to get more detailed explanations of the results before bringing different stakeholders into a shared debrief and action planning space. If you use this tool, my researcher brain would love to hear what trends you find. I also consult with schools who want support in improving their survey results, so if you’re interested, get in touch!

0 Comments

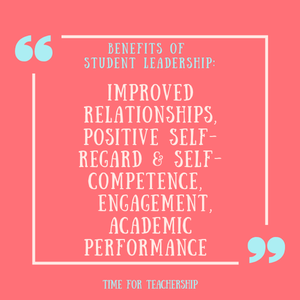

As we move towards more student-centered learning models in education, we may hear the term “student voice” more often. I hear it a lot in reference to giving students literal voice via talk time during class or giving students opportunities to choose which of 3 similar activities they would like to complete. However, the scholarly research on student voice reflects a higher level of student autonomy than the way it’s being used in practice. What is student voice? Dana Mitra’s (2006) pyramid of student voice reflects three levels of student voice. At the bottom, we’re listening to students. We might survey them once in a while, but the student involvement stops there. At the middle level of Mitra’s pyramid, students work with adults in partnership to accomplish school goals, maybe as part of a school committee or after school club focused on a particular initiative. At the top level is building capacity for student leadership. Mitra and Gross (2009) note student leadership is a powerful form of student voice, but quite rare in practice. The commonly accepted definition of student voice, put forth by Fielding (2001), is: students’ ability to influence decisions that affect their lives. I often adapt this during workshops with educators, embedding practical examples: Students have a voice in what, how, where, and when they learn. All Students as Leaders Unfortunately, in the instances where schools are offering opportunities for students to have a voice in decision-making and take on leadership roles, these opportunities are limited to the students who are already seen as “leadership material” by adults. The transformative power of student voice lies in all students having leadership potential. Lundy (2007) discusses barriers to inclusive, authentic student voice, and argues that to overcome these barriers, students need the following: the ability to form their ideas (which may require adult support in skills training or sharing information to help students arrive at an informed opinion); space to express their ideas; adults to listen; and the influence to inspire action (or at least receive explanations as to why action was not taken). Taking into account the importance of support from adults and school structures in helping all students fulfill their leadership potential, I created the following definition of student leadership: students working collaboratively to affect positive change in their educational environments with support from adults and mechanisms in the school (Lyons, 2018) Why promote student voice and leadership? Research has found lots of benefits to student voice in schools. Individual students who engage in leadership activities, have demonstrated improved peer and adult relationships (Yonezawa & Jones, 2007); positive self-regard, feelings of competence, student engagement (Deci & Ryan, 2008) and academic performance (Mitra, 2004). It’s not just individual students that benefit. The school as a whole benefits too! Additionally, when the decision-making process of an organization includes diverse stakeholder involvement, organizations make better decisions that result in improved organizational performance (Kusy & McBain, 2000). Students acting as representatives of various student groups also energize students that identify with them. Feldman and Khademian (2003) call this “cascading vitality.” Essentially, students inspire and empower others, lifting up students that may be experiencing structural, political, and/or social marginalization. Baumann, Millard, and Hamdorf (2014) remind us “preparation for active citizenship was a foundational principle of public education in America from its beginning” (p. 1). Not only should schools prepare students to be responsible leaders after graduation, we should provide authentic opportunities for students to be civically engaged while they’re still in school. Now that we’ve laid out the benefits of diverse students participating in authentic school leadership opportunities, ask yourself: How can I provide an opportunity for my students to have a voice in what, how, where, or when they learn? My last post talked about the value of choosing a few protocols for consistent use. Circles are my favorite protocol of all time. They democratize the classroom. Students are often more engaged than usual, and members of the class have the opportunity to learn about each other and build relationships. It’s good stuff. What is a circle protocol? Rooted in indigenous traditions and ways of being (Living Justice Press), circles are used to build community and resolve conflict peacefully. I was taught circle practice includes 5 main components: an opening ceremony, a closing ceremony, a talking piece, a centerpiece, and participants seated in a circle (with no desks or furniture in the middle). While you will want to co-create norms for your circle practice with your students, there are a few basic norms all circles need to have. First, all participants in the circle sit. This includes the teacher. Second, no one speaks without the talking piece. Again, this includes the teacher (unless there is a serious issue that needs to be addressed). Third, when a question is asked, the talking piece is passed around so every participant touches the talking piece and thus has an opportunity to answer. How do I plan for a circle? When preparing to introduce circle practice for the first time, I put up a list of the 5 components of a circle and explain them to students. Also, consider how you want to co-construct the norms for circles. (These norms will be your norms for the remainder of the year. You may revisit them or refine them as needed, but it’s important to try to do this well.) I use the circle protocol to have each student share one norm to start. Finally, you’ll want to think about your first circle topic. For a first circle, it’s nice to choose a topic that helps participants learn about each other. You also want to choose a topic that everyone can easily talk about. I often use “Story of My Name,” in which all participants share their name and a story about it (e.g., how they got their name, what it means for them, if people mispronounce it). Once you’ve had the first circle, planning for future circles is focused more on the core questions you will pose to students. I typically backwards plan circles from the purpose. I think about what I want students to get out of the circle. Then, I consider the main question I want them to discuss. From there, I pick a few scaffolding questions if I think they need it (we may need to define common terms or concepts and get on the same page so that everyone can access and respond to the deeper, focus question). Then, I choose an opening and a closing. Sometimes, I’ll re-use the same opening in multiple circles (e.g., “In one word, share how you’re feeling right now”) or the same closing (I used “Clap once in unison—without counting down”). Often, I will share a relevant quote for the opening and/or closing. You can also plan a more involved activity or protocol within a circle (like inner circle/outer circle share), but most of the time, I keep it simple. How do I facilitate a circle? There are a few tips I try to keep in mind while facilitating. Most importantly, the facilitator is a model for how the talking piece works. Don’t talk without it unless absolutely necessary. If side conversations happen, I try to redirect students with my eyes and then address the problem when the talking piece gets back to me. As a facilitator, it’s good to wear a watch or have another way to keep track of time. A full go-around for one question takes longer than you might think. When you’re short on time and unsure if you’ll be able to complete one more round/question, you can add a time restriction to your question or prompt. (I usually use, “Answer this next question in one sentence.”) I want to learn more. What resources are available to me? There is a lot to think about when you first start using the circle protocol, so I made you a free circle-specific lesson planning template. I initially created this for students when I asked them to plan and run their own circles, which was a big success. So, you can use this template for yourself and for students once you get to the point where students are familiar enough with the circle protocol to take the lead! This book has premade circle lessons that are phenomenal. It contains relevant sections including, but not limited to: getting started with circles, co-creating norms for circle practice, discussing issues of equity, circles for staff and parents, and restorative discipline and conflict resolution circles. Morningside Center is the organization that trained me. Members of this organization wrote the suggested book above. Their site routinely publishes current events circles on topics that emerge in the news. These are excellent resources to address students’ SEL needs and discuss how students are experiencing (or not experiencing) values in their lives in school, outside of school, or when reading/watching the news. Early in my teaching career, I planned lessons with the intention of coming up with as many different activities as possible. As I gained experience, I realized some activities (or “protocols”) worked better than others. I identified protocols that routinely engaged students in learning. I started re-using those, which improved overall student engagement and reduced my planning time. Talk about a win-win! What is a protocol? EL Education suggests a protocol skeleton includes:

Basically, a protocol is an activity. I use the term “protocol” because as a certified EL Education coach, I’m used to their terminology, and I like that it distinguishes the step-by-step nature of a protocol from a structureless activity. Use whatever language you prefer, just know these 3 components are important for student success! Why should I re-use protocols? EL Education, creators of this (totally free) research-based ELA curriculum, found that “Teachers are often most successful when they choose three to five protocols that anchor their instruction and focus on these.” When we re-use protocols that students are familiar with, students are more likely to participate, remain accountable, and spend more time learning (and less time trying to figure out the steps of a new protocol). It also promotes student independence and ownership of the learning process. Sometimes, teachers worry that students will become bored with the same protocol over and over. While that has happened to me, it typically happened months into heavy repetition. The key is to make the content or question students are grappling with engaging enough to hold their attention, so they are less focused on the protocol and more on what they’re talking about. Re-using protocols is particularly helpful for students with IEPs, as students with various dis/abilities (e.g., Learning Disability with a processing delay, Autism Spectrum Disorder) benefit from routine and consistency, as clear instructions reduce the cognitive load for students, freeing them up to focus on the learning (Impact). What are some protocols options? EL Education suggests having designated protocols for different purposes. I’ve slightly adapted their list to include the following: engaging with text, discussion, peer feedback, group decision-making, presenting, and independent work time rotation. For specific protocol ideas aligned to these purposes, consider what you already do that works well for your students. Build on your strengths! If you haven’t found any protocols that work well yet, I suggest looking at these great resources:

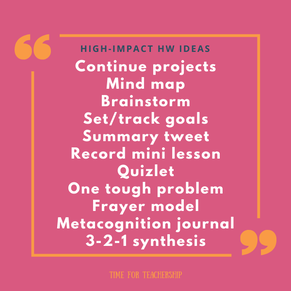

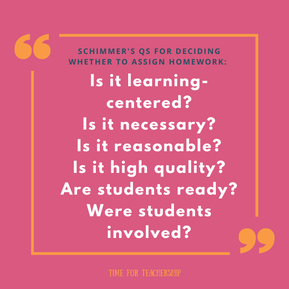

Try to identify 1 protocol per category and stick to these. You may want to structure your protocols to repeat regularly (e.g., on a particular day of the week, at a particular place in the arc of each unit). Make a list of your chosen protocols, and use this list when lesson planning to save time. What are your favorite protocols? How often do you repeat them? So, you’ve decided to give homework. If you haven’t read my previous post, “Should I give homework?”, go back and read that first. Perhaps you haven’t decided one way or the other, but you’re interested in seeing some examples of high-impact homework. Many of the following examples could be used as exit tickets as well as short homework assignments. The examples provided are aligned to John Hattie’s (2018) work on strategies that most impact learning. The effect sizes reported are indicators of the strength of the relationship between the activity and student learning. To give you a sense of what the numbers mean, a large effect size is 0.8 and up, a medium effect size is around 0.5, and effect sizes around 0.2 are small. Continue projects started in class. Activities involving cognitive task analysis “require a lot of cognitive activity from the user, such as decision-making, problem-solving, memory, attention, and judgment.” This kind of activity has a 1.29 effect size, the largest of any student activities! Students should be asked to think through multiple steps to solve a large problem or complete a complex task. Create a mind map. You could use this to jumpstart a unit or introduce a concept, connecting the topic to things they already know. Having students integrate new learning with prior knowledge has a 0.93 effect size. Another approach would be to have students map out the connections after a lesson, in the middle of a unit, or at the end of a unit. Concept mapping has a 0.64 effect size. You can have students create a mind map on paper or use a digital program like Coggle. Brainstorm. If you’re just starting a unit, you may want to offer students a compelling image to take home and write down what they notice and wonder. This could provide some good conversation the next day in class, kicking off the new unit with high student engagement. Again, integrating prior knowledge has a 0.93 effect size. Set and track goals. Student self-efficacy has a 0.92 effect size. Goal setting and tracking progress towards those goals has been shown to improve students’ self-efficacy (Schunk, 2003), and simply having a learning goal has a 0.68 effect size in relation to student learning. Click the button below to get my student goal setting template. It's a Google Doc, so you can make a copy & edit it! Summary tweet. Simply asking students to summarize what they learn or read has a 0.79 effect size. When you limit the amount of writing required, students may be more willing to complete the assignment because of the short length. Choosing this approach, you’re less focused on writing stamina, and more focused on developing students’ ability to think critically. They have to be able to decide what’s most important to distill an hour lesson or a week’s worth of lessons into a short blurb. Record a mini lesson. Having students teach each other (reciprocal teaching) has a 0.74 effect size. You can read more about what reciprocal teaching is and the brain science behind it here. Asking students to use a tool like Flipgrid or Screencastify to record a video of themselves teaching a mini lesson (explaining a concept learned in class, perhaps with a visual) will help them internalize the learning. Additionally, you can select some of the best videos for your personal resource library. Sometimes, students learn best from other students, so for the students who are still struggling with the concept, have them watch a student-made video. It might just click for them! Quiz yourself on Quizlet. Sometimes, maybe for standardized test prep, we may need students to memorize basic facts. Rehearsal and memorization practice has a 0.73 effect size. I like Quizlet, and I like teaching students how to make their own flashcard decks on the app, as it helps them take ownership of their study skills. Students can play different games with the same deck, and the app tracks their progress and highlights cards they need to study more. Spaced practice has a 0.60 effect size when compared to mass practice (learning information once and not coming back to it). So, Quizlet is a great way for students to review older material, not just that day’s lesson. For example, one curriculum suggests reviewing at 2,6,15, and 30 days after the initial lesson is taught. Tackle one tough problem. Problem solving teaching has a 0.68 effect size. It works best when it’s well structured and students have access to the relevant concepts and have all of the necessary information. It’s also ideal to do an initial brainstorm in class to have students start thinking about the problem and make sure everyone starts strong. You could also provide an online space for students to talk outside of class to brainstorm problem solving approaches. (This could be in teams or whole class.) One challenging problem for the night is enough! Fill out the Frayer model for vocab. Vocabulary programs that provide definitions and context and offer multiple exposures to words over time have a 0.62 effect size. The Frayer model asks students to go beyond simply defining a word, also requiring them to think of examples and non-examples of the word. See more information on the Frayer model here. Metacognition journaling. Metacognition strategies have a 0.60 effect size. Having students think about how they think (and articulate that thinking—in writing or by video journal) is valuable. You could have students brainstorm a list of different approaches to solve a problem. So, assign one problem and tell students the goal is not to come up with a solution, but to come up with the longest list of ways you could go about solving the problem. (You could also have students solve the problem itself, but the emphasis here is on having students consider different approaches, not getting a “correct” answer.) Alternatively, you could have students solve a problem and then explain why they approached the problem the way they did. Or, you could ask students to reflect on a day or week of school and explain which strategies have been working for them (i.e., leading to more learning) and what changes they want to make for the next day/week. 3-2-1 Synthesis. Combine some of the above ideas in a 3-2-1 reflection format. For example: write 3 things you learned (summary), 2 problem-solving strategies you used today (metacognition journaling), and 1 thing you want to learn or work on tomorrow (goal setting). Whichever type of homework you choose to assign, remember to keep it purposeful and mangeable. You want to promote thinking and learning, not overwhelm and exhaustion. As you try different strategies, check in with your students. See what’s working for them. Ask them for their thoughts, and maybe let them choose which homework would be most effective for them. Remember, we’re trying to build student independence. If we can introduce students to various learning strategies that can be applied in different contexts and we help them see why and how these strategies are effective in improving learning, we gain student buy-in for doing the work and we prompt them to think about which activities help them learn best. Homework prompts interesting debate among educators and educational scholars. Anecdotally, I found my students were successful with minimal prescribed homework. In this post, I want to review what the research says on homework and then share what I did in my class. What does the research say? One study found that students are spending much more time on homework than they were 20 years ago. Interestingly, there’s a gendered component here as well, with girls spending more time on homework than boys (Pew Research Center). Another study found students are receiving up to 3x the amount of recommended homework, and even kindergarteners (who researchers agree should not be given homework), have 25 minutes of homework per night (CNN). Does homework help students? It’s complicated. In Cooper, Robinson, & Patall’s (2006) meta-analysis, they found homework has a stronger positive correlation with academic achievement on standardized tests. The positive relationship was stronger in grades 7-12. They suggest homework may improve study habits, attitudes toward school, self-discipline, inquisitiveness and independent problem solving skills, but they note the empirical evidence on this is limited. They also warn that too much homework can be counterproductive. Should I give homework? Vatterott (2010)’s 5 hallmarks of good homework are that it is: meaningful, purposeful, efficient, personalized, doable, and inviting (Minke, 2017). It should serve a purpose, have meaning for students (i.e., connect to what students are learning in class), and relate to their interests and ways of learning). It should spark curiosity! This helps students love learning. The challenge should be appropriate, so make sure students can do this work independently. Not sure they can? Save the practice for class time, and assign the mini lesson for homework! The purpose is particularly important when designing your curriculum. ASCD emphasizes the importance of assigning purposeful homework, stating “legitimate purposes for homework include introducing new content, practicing a skill or process that students can do independently but not fluently, elaborating on information that has been addressed in class to deepen students' knowledge, and providing opportunities for students to explore topics of their own interest.” NEA lists homework purposes as: practice, preparation, extension, or integration. Schimmer (2016) suggests asking yourself the following questions when determining whether to give homework to students:

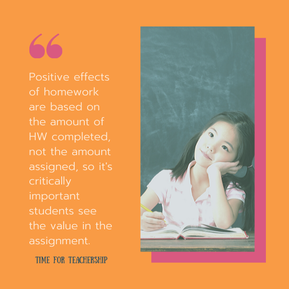

If you can say “Yes” to all of these questions, go ahead and assign the homework! If you answered, “No,” consider re-working the assignment, flipping the instruction, or skipping the homework for the night. How much should I assign? The general rule for calculating the maximum amount of time students should spend on homework each night is to multiply the student grade level by 10 mins. (For example, 3rd graders should have no more than 30 minutes of homework per night.) This is the total for all subjects, so if you only teach 1 subject, keep in mind your homework should take a fraction of that time (ASCD). Also, keep in mind that most of the research on homework indicates that the positive effects of homework are based on the amount of homework completed, not the amount assigned, so it’s critically important students see the value in the assignment, or they will not do it and there will be no benefit to assigning it. In fact, if that’s happening, I students are likely losing motivation to learn and seeing themselves as a “bad student,” leading them to further disengage. What should I do with completed homework? It depends on the purpose. If you’re assigning homework as a way to help students build study skills, just checking that it’s done should be enough. If the assignment is part of a larger assignment (like a rough draft of a paper), it’s helpful to give students feedback on their work as opposed to just checking that it’s done. Note the difference in purpose—work habits versus skill mastery. Walberg (1999) found teacher comments on homework to have a higher impact on students’ academic achievement than simply giving a grade (ASCD). In my classes… In my high school classes, I used homework as a time for completing project pieces they did not finish in class. So, my homework assignments had an integration or application purpose, and they were always started in class. The application element builds academic achievement, but it also teaches study skills and time management, as I would give students time to work in class, and then if they needed more time or worked inefficiently during class, they had homework. In my college classes, simply because we have less class time, I use a flipped classroom method, assigning readings/viewings as homework and then use class time for independent application or class discussions, so I can provide formative feedback and correct misconceptions during class. This also reduces my out of class grading time, as the feedback that Walberg (1999) found helpful to student learning, doesn’t always need to be written! When and what do you assign as homework? How do your students engage with it? Do you measure its impact on student achievement? Have you ever opened your email and become overwhelmed by the sheer number of unopened emails that you decided to avoid your inbox altogether? I have. Emails are so stressful! Unfortunately, email is usually necessary for us to be able to do our jobs, so we can’t avoid it forever. However, we can be strategic about the organizational systems we use and the boundaries we set around checking our email. By establishing these systems and sticking to firm boundaries, we can reduce the stress caused by email. Who’s ready for that? Let’s talk about boundaries first. We need a head-heart combo to tackle this problem. This step is the heart portion. Sleep Advisor reports 55% of Americans check their email within an hour of waking up, before they even get to work. A frustrating email can set the tone for your whole day! I know I stress over a negative email or an email that asks me to a ton of extra work. Shifting when you check your email radically change how you experience your day! Maybe your school requires you to check email as soon as you get to school, but that does not mean you need to check email outside of work hours. Also, when you respond to emails outside of work hours, you are communicating to people (colleagues, bosses, students, parents) that they can expect you to be routinely reachable at home. While it may be inconvenient for others to not get an immediate response from you, you have no obligation to communicate outside of work. Email is asynchronous by nature. Respond when you are able to respond. If you’re worried about someone not being able to contact you, set an away message to let them know you check your email at a particular time. If necessary, give them another way to contact you in an emergency. I have set the following boundary for myself: I will check email at 3:00PM each day, and I will not to look at my email before 3:00PM or after 4:30PM. I set aside 30-60 minutes to address every email—reading, responding, deleting, or taking action immediately—so I don’t need to worry about it once my workday ends. Pew Research found that 88% of smartphone users actively check email on their phones. I used to do this. It made me constantly accessible. So, I set another boundary. I turned off email notifications on my phone. No messages appear on my screen, and no unread email number appears on the app icon. I only check it when I need to quickly look up information from an email. Now, take a moment to set whatever boundaries you want to set for yourself. Just remember, that your time is your time. You are not a teacher 24/7. You need time to be unreachable and not-at-work. That time is necessary to rest, recharge, and allow you to be your best self at work the next day. Now, let’s think about organizational systems. We’ve tapped into the heart to set boundaries. Now, we need your head for some strategic thinking. I’m sharing some sites and apps that have helped me streamline my email organization. Unroll.me This website is amazing. As a person with a list of email subscribers, it seems counter-intuitive for me to share this, but I truly want your inbox to be free of anything that doesn’t need to be there—all email should be necessary for work or adding value to your life. By having less emails in your inbox, you create time to read the ones you want to read. (I believe what I send my email subscribers each week has the potential to add real value, but if these emails are not helping you be a better teacher, by all means, unsubscribe!) The unroll.me site lets you quickly unsubscribe from email subscriptions you no longer want (or maybe didn’t know you were subscribed to). They also let you choose a few subscriptions to roll into 1 email if you’re aiming for fewer unread emails. Gmail’s “Configure Inbox” Option I select all of the options, including adding starred emails to my primary list. When I check my email, all of the promotional emails or social media updates are not part of my primary list. I want my primary inbox to include emails from humans, not automated messages or listservs. If something does make it to my primary inbox that shouldn’t be there, I click on the 3 dots, select “Filter messages like this” and create a rule for those emails, redirecting them to “promotions” or another relevant section. I can also do the opposite (move types of emails from promotional to primary). This helps reduce overwhelm when I use the Gmail app on my phone. I have multiple email accounts, so I set it to “All Inboxes,” combining just the primary inboxes of all of my accounts and saving myself precious time I would have spent sifting through junk! Boomerang Chrome extension Having trouble with your boundaries? The Boomerang extension allows you to pause your inbox. This way, you won’t see new emails until you decide to click “Unpause.” If you think of a work email you want to send, but it’s outside of work hours and you want to stick to your no-email-outside-of-work boundary, you can schedule the email to be sent as soon as you’re back at work. This respects others’ email boundaries and does not let people think you’re on email at home. Gorgias This one helps you save time responding to emails. If you find yourself frequently sending the same kinds of emails, try the Gorgias extension. You can save templates for commonly sent messages and access them once you open a new email. You can personalize it as needed, but it’s nice to have the basic language come up with a click of a button. Set your boundaries and implement some organizational systems that will reduce your email overwhelm. This is the year you take your life back from your inbox! Go get ‘em, teach! As educators, as givers, as women (for those of you who identify as women), we are conditioned to say “Yes,” to agree to help others. It is hard to say “No,” to set boundaries for ourselves, to carve out space for our wants and needs. Let 2020 be the year you turn that around. Interested? Let’s figure out how to make it happen. Saying “No” enables you to say “Yes.” In order to set our boundaries, and be able to say “No” like a boss (you are the boss of your life, after all), we first need to change our perception of a “No.” Saying “No” to one thing enables you to say “Yes” to something else. That something else may be spending time with family, exercising, sleeping, whatever it is, your “No”s make room for “Yes”es in the areas that matter most to you. Remember, there is always an opportunity cost to saying, “Yes.” You need to determine if the cost is worth it. (For example, if I agree to stay after school, I won’t be able to run today or cook dinner with my family or fill-in-the-blank-here. Am I willing to sacrifice that?) What do you want to say “Yes” to? Take a moment to brainstorm and list your top 3 priorities. What do you want to spend more time doing? This list will help you say “No.” You can use the list as a litmus test by asking yourself if saying ”Yes” to something will take too much away from your priorities. Deepak Chopra reportedly has 3 questions to which he needs to answer “Yes” in order to agree to take on something new: Is it fun to do? Are the people I would be working with fun to be with? Is it of service to the world? This is how you say, “No.” Make sure your brain is ready. Remind yourself of your priorities. Keep a post-it near your desk reminding you it’s okay to say “No” or listing your top 3 priorities or asking “Is it worth the cost?” Say: No. As a full sentence. Count to 10 in your head afterwards to fill the awkward silence if it bothers you. In Emilie Aries’ book, Bossed Up, she notes a moment when Anderson Cooper asked Hillary Clinton if she wanted to respond to a comment, and she simply replied, “No.” Complete sentence. Boom. We don’t always need to explain ourselves! If the idea of not explaining your answer is stressing you out, try sharing your priorities as an explanation. I’ve heard different iterations of the following script: Thank you for asking. I’m excited about what you’re doing. My current priorities are: ____, ____, and ____. I’m unable to say yes to anything outside of these right now. (You can suggest an alternative option or a way to integrate one of your priority areas with the ask, such as: If you want to join me on my afternoon run/walk, then I would be able to have that meeting.) Honor others’ boundaries Model accepting others’ “Nos” with not just politeness, but excitement! Support your colleagues and loved ones to set boundaries of their own and honor those boundaries when they say “No” to you. In fact, give those “No”s a little cheer or high 5. Acknowledge that boundary setting is hard and important, and they are modeling like a champ! Remember, we get to make the calls about how we spend our time and energy, especially outside of work! Our time and energy are finite resources, and we often give and give and give until there’s nothing left for what’s important to us. Emilie Aries often talks about the martyrdom mindset, pointing out in her book, “research shows that happier, healthier people are more productive, focused and harder working. Taking care of your basic needs has been shown to improve decision making, increase creativity, and help with problem solving and efficiency…it leaves you in a stronger position to do better work, help more people, and have a bigger impact,” (p. 20). Setting those boundaries so you can invest in feeling energized and fulfilled actually helps you thrive at work and at home! Need some reminding to help you stick to your boundaries? Get my free boundary reminders, 4 mini posters, that you can print and post in your workspace or set as the background of your computer or phone! Now that you’re ready to get started, what are your priorities for 2020? What boundaries will you set? |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed