|

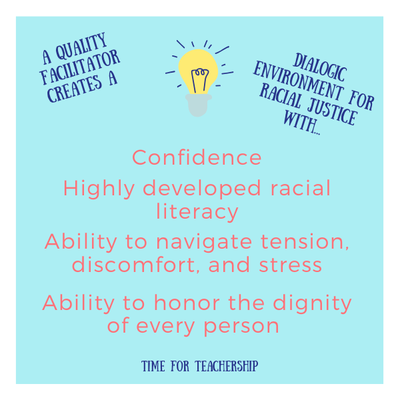

6/22/2020 At the Intersection of Racial Justice in Education, 4 Keys to Talking About Racism in Schools: #1 A Liberating Dialogic EnvironmentRead NowThe demand for racial justice is loud and clear. The concept of antiracism has transformative potential to realign and invigorate conversations around racism and can direct us toward “liberating new ways of thinking about ourselves and each other” (Kendi, 2019). As we plan to make our schools sites for antiracism work, we may wonder where we should focus our action. I’ve written previously about critically examining our policies and pedagogy, but we also need to be able to strengthen our ability to have generative racial dialogue—with colleagues and students. For advice on this, I turned to my brilliant colleague, Dr. Cherie Bridges Patrick. Her research on racism denial in workspaces examined the ways in which racial dominance is (re)produced in everyday professional interactions, often without intent. We have combined our expertise to merge racial justice into all aspects of education. In the course of her research, the term racial dominance is used to express the combination of racism and whiteness. These are complex concepts, in part because their destructive nature is obscured and often consists of what is not said, what is not obvious, or what is imperceptible. Ibram X. Kendi, author of How to be An Antiracist, argues that “the only way to undo racism is to consistently identify and describe it—then dismantle it.” Dr. Bridges Patrick’s work interrogates discourse—text and talk—to help expose, deconstruct and name patterns and processes in discourse structures. In talking to Dr. Bridges Patrick, I asked what educators could do to address the issue of perpetuating systemic racism and the dominant presence of whiteness in schools. The first step in identifying and describing racism requires an ability to talk about it. She recommends building educator capacity to effectively engage in productive conversations around race while also ensuring measures of accountability for schools and educators who commit to doing this work. Four capacities or characteristics that contribute to fruitful racial dialogue emerged from Dr. Bridges Patrick’s research: 1) readiness and willingness; 2) vulnerability; 3) adaptability; and, 4) a positive, encouraging, liberating dialogic environment. First, let’s unpack the most foundational element of racial discourse capacity building...a positive, encouraging, liberating dialogic environment. What does that entail? Driving the necessity of a dialogic environment is the notion that many of us don’t know how to talk about race, which often results in various forms of denial including willful avoidance and silence (often driven by a desire for comfort). An example of a denial strategy is offered because they are often present in racial dialogue. In her thematic analysis, Dr. Patrick found several discourses of denial, one of which was comfort/discomfort. Discourses of comfort/discomfort are about maintaining white comfort without consideration of the costs to others. Emergent data suggested that comfort served to prioritize the needs of white professionals at the expense of their non-white colleagues. Comfort is often undergirded by fear and insufficient skills to navigate the discomfort of racial dialogue. A white professional in the study stated: “there’s a fear, I think that kind of what I was talking about before, like, there’s this elephant in the room, but you’re scared to like say the wrong thing… step on someone’s toes, be perceived as racist.” Building skills to navigate racial dialogue will be part of the upcoming discussions on the interpersonal aspects found in the remaining three discourse capacities. Positive, Encouraging, Liberating Dialogic Environment. The dialogic environment is led by a confident facilitator with highly developed racial literacy and an ability to navigate the tension, discomfort, and stress that accompany racial dialogue, while honoring the dignity of every person. When describing this type of environment to me, Dr. Bridges Patrick clarified that this is not a “safe space,” but a generative one, one that is free of physical and emotional violence and exudes an atmosphere where people can be vulnerable. In her research, she further explains this environment is not specific to one space. She writes, “Whether a classroom, office space, or coffee shop, the environment can be liberating when grounded in dignity, and the humanity of all is recognized and honored.” This environment includes online environments given our current shift to distance education. She continues, “The liberating dialogic environment is a space where tension, conflict, and challenge are invited and used for information and transformation. “The dialogic space is one where disagreement is needed and must be expected, and strong emotions are seen as expression rather than personal attacks” (Bridges Patrick, 2020, p. 172). Feminist scholar and social activist bell hooks (2000) supports the need for disagreement. She argued that work around revolutionary feminist consciousness-raising could occur “only through discussion and disagreement,” from which participants could begin to gain a “realistic standpoint on gender exploitation and oppression” (p. 8). The work of antiracism requires a similar stance. Amidst the serious nature of racial discourse, Dr. Bridges Patrick also highlights, “Laughter is critical to this work and the environment should allow for levity.” In Dr. Bridges Patrick’s research focus group, emotions were invited while dignity and humanity were positioned as nonnegotiable by these comments: “We can be angry, we can be frustrated, we can be whatever . . . but, at the end of the day, when we leave this Zoom room, we should all have our dignity and humanity intact and recognize that shared humanity” (p. 172). Facilitating a space for racial dialogue requires the centering of dignity - the notion “that all human beings are imbued with value and worth” and a sense that all persons are honored as contributing to the collective (Hicks, 2011, p. 4). Honoring the dignity of others is not connected to the unique qualities or accomplishments of people, rather it is the belief in one’s inherent value and worth no matter what they do. Dignity then is an intrinsic part of being alive and cannot be granted through authority, only honored or violated (dishonored). Treating people poorly because they have done something ‘wrong’ perpetuates the cycle of indignity and we violate our own dignity in the process. To help you further understand the elements of dignity as you engage in conversations ripe with disagreement, we’ve put together a free resource you can use with colleagues and with students. Click the button below to get a 1-pager, summarizing Dr. Hicks’ 10 elements of dignity as well as a student-facing poster of the elements, which can be a great starting point for developing class agreements next year.

1 Comment

|

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed