|

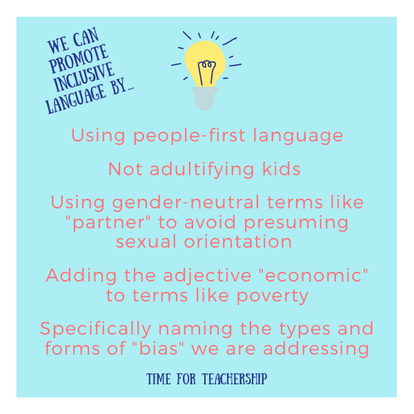

This post is the second of two on inclusive language in educational spaces. If you haven’t already, please go back and read Part 1, which introduces the importance of inclusive language and covers terms related to gender and race. Once you’ve done that, you can return to this post, which addresses what I’ve learned about language related to other axes of identity. Ability. People-first language is something to keep in mind for all descriptions of people. When referring to students with IEPs, we can use the term “students with IEPs” or “students with dis/abilities” (I use the “/” to recognize some dis/ability activists prefer terminology that is less deficit-based while other dis/ability activists prefer the term “disability”. As a teacher, I have gotten caught up in educational shorthand and said “SPED students,” but I want to eliminate that phrase because it’s not people-first language. Terms like “handicapped” and “cripple” are not acceptable terminology. When referring to a person who uses a wheelchair, we can literally say that (“uses a wheelchair”) or we could use a more general term like “a person with a physical impairment”. Of course, we don’t use phrases or allow students to use phrases to demean others, but I just want to note that terms like “moron,” and “idiot” originated as offensive terms used against folx with mental impairments. If we hear students use this language, we can explain why this is harmful for multiple reasons. Age. This one overlaps with race. White supremacists have infantilized and oppressed Black men in the U.S. through use of the offensive term “boy.” While this should be commonly understood as racist, a similarly problematic use of age-inappropriate terms may be affecting Black children in our classes. Studies have shown Black children are seen as older than their age compared to white children. This is called “adultification bias.” (While many studies have focused on Black boys, this is also a problem for Black girls.) This is particularly problematic as adultification bias often results in increased rates of discipline or increased use of physical force against Black children. LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer). When referring to a spouse or person that a student or family member or colleague is dating, using the term “partner” is more inclusive than “husband” or “wife” or “boyfriend” or girlfriend.” It encompasses all genders and does not assume the person’s sexual orientation. Also, when referring to families in a same-sex relationship or teaching about marriage equality, the phrase “same-sex” is preferred to “gay marriage.” Socioeconomic Status. My brilliant professor, Dr. Philomena Essed, helped me change my language from terms like “poor” and “poverty” to be more specific (e.g., “economically poor” and “economic poverty.”) The first set of terms implies a total lack of wealth beyond money—a lack of values, dignity, etc., but in being specific (adding the adjective “economic,”) we can uphold the person’s dignity. The term “low-income” also works here. Issues. When discussing students facing housing insecurity, rather than saying students are homeless, we can a student or family is “experiencing homelessness” or “experiencing houselessness” (this term acknowledges “home” is more than a physical structure) or “living in temporary housing”. Recently, I heard Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley say one of her constituents told her he preferred the phrase “food aparteid” in place of the more commonly used “food desert,” explaining people in his neighborhood are capable of growing their own food, but the system has not provided access for them to do so. Bias. Generic words like “bias” can sometimes be used to cover up specific injustices. If we don’t specifically name what we are talking about, we cannot address the oppression. Anti-bias training can be helpful, but without naming the specific ways bias is enacted (e.g., racism, sexism, homophobia) and the various forms oppression can take (e.g., interpersonal, institutional), it can lessen the impact of the work. It’s not that we have to throw out the term, we just want to be mindful about naming specific oppressions and not focusing on individual acts of bullying at the expense of tackling the policies and structures and systems that perpetuate the oppression. Finally, there are many phrases that I hope are so obviously inappropriate I don’t need to list them. Two that I thought were gone, but I’ve actually heard educators say recently include: “That’s gay” and “That’s retarded.” Let’s stop using these phrases. Instead, say what you actually mean (e.g., “That’s ridiculous.”) To help you keep all of these terms top of mind, I’ve condensed the big takeaways onto one page you can use as a quick reference. Of course, there are many examples I have not included in this list and far more I’m not yet aware of, so I welcome additional contributions in the comments below. I’m looking forward to growing and learning alongside my fellow educators.

0 Comments

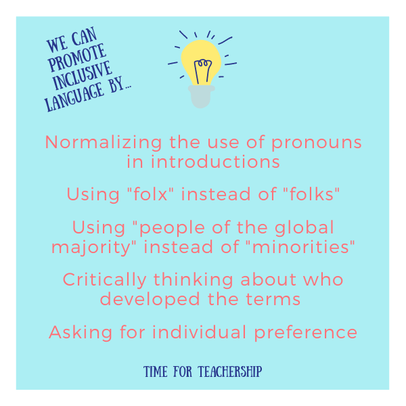

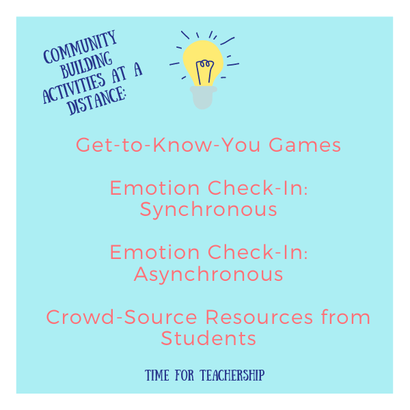

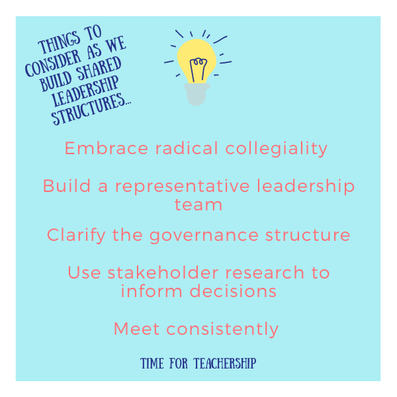

Language is so important. The words we use to refer to people and the issues people face carries a great deal of weight. While it may be cumbersome to unlearn old terminology and start using new words and phrases, if a group of people are saying certain phrases hurt, it’s necessary to listen and work to change our vocabulary. Ayanna Pressley says “the people closest to the pain should be the closest to the power.” I think this applies to who gets to determine the language we use. If people have experienced the pain of inappropriate or offensive language and I haven’t, I want to listen and learn and do my best to follow the recommendations of the people “closest to the pain.” As we enter a new school year already filled with anxiety, this is particularly important for us as educators to recognize, as we may be harming students or families with our word choices. For many of us, we may not know better, so I hope this post helps us know better, so that (in the paraphrased words of Maya Angelou) we can do better. Before I share some of the things I’ve been learning with regard to specific identity groups, I want to say there is much I have yet to learn. Please share any additional information I’m likely missing or any corrections to what I’ve shared. Also, as a general rule, I like to listen to how people self-identify (or ask if this information is not shared), as each person may prefer different terminology, and it’s important we use the terms our students, family members, and colleagues want us to use. Gender. A powerful practice for the start of the year as you ask students to introduce themselves and you introduce yourself is to ask for (and state your own) pronouns. This is a great way to normalize asking for a person’s pronouns, start a conversation about pronouns and their importance, and prevent any misgendering of students. You could encourage students to add their pronouns to their “screenname” for video conferencing and in their email signatures. Additionally, I have recently been trying to use the spelling “folx” instead of “folks” to intentionally include queer or GNC (gender non-conforming) people. Race. Firstly, race is an adjective, not a noun. For example, in the phrase “white people,” white is an adjective, whereas “whites” is an example of using race as a noun. The term “minorities'' is often used to refer to people who are not white, but it’s a relative term. In a specific school, the majority of students may be white, but globally, white people are the minority. This is why I want to start using the term “people of the global majority;” it flips white supremacist language and the assumptions behind it on it’s head. Some folx like the term “people of color,” but this term has also been critiqued for its normalization of whiteness (ignoring that white is also a color) and for being US-centric. BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) is a term that names specific racial groups, which is helpful when discussing topics that are particularly relevant to the listed groups (e.g., police brutality and mass incarceration). When calling out racial injustice, we want to be specific, making it clear which groups are disproportionately affected. “Latinx,” (pronounced La-TEEN-ex) a term inclusive of all genders, is typically preferred over the term “Hispanic,” as the latter was imposed on Latinx people and reflects Spanish colonialism. Although, I have also worked with a “Hispanic-Serving Institution” that surveyed students about their preference, and the students said they preferred the term “Hispanic.” This served as a reminder to me that asking students’ preference is best practice. Another reason to ask is that some groups will prefer a more specific term than the broad “Latinx” like Chicana/o for folx of Mexican descent. “Indigenous” or “Native peoples” are terms I’ve seen most commonly used by Indigenous activists and scholars. However, some prefer American Indian. That said, the term “Indian” refers to people from the country of India, not people indigenous to the North American continent. The word “Oriental” describes material items, like rugs, not human beings. Asian is the term used to describe people. Terms like “Middle East” and “Far East” come from British colonialism, normalizing Britain as a reference point. Terms I have heard used in place of the “Middle East” include “the Arab world” and when referring to people from this region of the world, the acronym “AMEMSA” (Arab, Middle Eastern, Muslim and South Asian) can be used. Other problematic race-related terms I have heard used in schools include “gyp” (an offensive reference to “gypsies,” for whom the accurate term is Romani people; “Eskimo” (a label assigned to the Inuit people by colonizers), and “ghetto” (a racialized and classed term that is rooted in the religious oppression and physical segregation of Jewish people and has since been used as a racially coded adjective that perpetuates stereotypical attributes of low-income Black communities). “Diverse” is another term that in itself is not problematic, but how it is used can be. If we refer to a school as “diverse” and it’s 95% Black, that’s not diversity, that’s a predominantly Black school. Using the term “diverse” as synonymous with Black is just not accurate. There are many more identities to discuss, so I will continue the conversation in the next post. I also want to acknowledge once again there are many terms I may not have talked about here, and there are likely mistakes I have made because I haven’t learned to correct them yet, so please feel free to share corrections or additional insights. I’m on this journey of growth along with all of you. This fall, many educators will be tasked with building community in their classes without seeing students in person. Developing relationships with students and creating a thriving class culture will look different in the online space, but it’s not impossible! Let’s look at some things educators are considering as we prepare to build class community this school year. Time Given the distance learning setting, many teachers are realizing it will take longer to build community this year. I think that’s completely okay! If we think about the necessary conditions for learning, feeling a sense of belonging and connection is one of the factors that will support student learning throughout the year. It’s valuable in the long-run to take time to develop it early on. I’ve heard many school districts tell teachers the first 1-2 weeks are for community building only. No academic content is to be taught. As you think about your context, consider how long you can spend at the start of the year and also how often you want to intentionally build community as the year progresses. You could even calendar it out. Goals Community building encompasses a lot. I find it helpful to identify my goals for community building and backwards plan activities from those goals. Basically, backwards planning without the academic standards. Some goals I’ve heard teachers share this summer include: providing time for socialization, helping students name emotions and share stress reduction strategies, and learning about student interests and learning preferences. As always, the start of the year, will also involve co-constructing class agreements with students. This year, that may include agreements specific to the online space, such as whether/how students should raise a hand before speaking or if they should just unmute and share when ready. Activities As you plan the specific activities you’ll want to use to engage students in community building, you might consider how you can use these community building activities to introduce and practice the tech tools or protocols students will need to use during the year. Here are some examples that could build community and tech tool/protocol proficiency. Get-to-Know-You Game. At the start of each class, share one statement at a time, and ask students to turn off their video cameras if the statement is NOT true for them. If the statement is true for them, they keep their camera on. This is a great way to help students learn about each other and also become familiar with how to turn on the video camera. Alternatively, if you’re using Zoom and plan to use the annotation feature during the year, you could adapt the activity to practice that skill. You could share a slide with the statement listed and ask students to write their initials (or place a stamp if you want it to be anonymous) if the statement is true for them. Emotion Check-In: Synchronous. You could also use the start of each class to ask students to share how they are feeling in the moment. This helps students name their emotions and gives you a sense of how everyone’s doing. How you ask students to respond will depend on the tools or protocols you want students to practice. You could ask students to type how they are feeling into the chat to practice locating and using the chat feature. This could be a private message sent to just you or a public message sent to the whole class. You could use a protocol like Pass the Mic to practice having a virtual discussion. In this protocol, a student says “I’m passing the mic to ____” after they are done sharing until everyone has had a chance to “hold” the mic. You can offer students an option to say “Pass” just like an in-person circle. Emotion Check-In: Asynchronous. If you want to provide a space for students to check-in throughout the week when you are not seeing them live during class, you could set this up using additional tech tools students will be expected to use during the year. You might want students to practice using the Learning Management System (e.g., Google Classroom, Schoology, Canvas), so you can set up a discussion thread inviting students to type, add an audio note (students can do this by using Vocaroo and pasting the link in the discussion thread), or by asking them to respond using GIFs. (To do this, students would click the button to respond to the discussion thread, then select Add > Link, and then paste the GIF link). You could also ask students to complete a Google Form that asks 1-2 emotional check-in questions. If you will want students to take quizzes with a tool like Google Forms, this is a low-stakes way to practice accessing and submitting a form. Finally, if you’re using another tool like Flipgrid or a blogging site, you could have students post their check-ins using those tools. In the spring, one school in New York had students post to a blog visible to the school community, which enabled students’ former teachers to see how students were doing and reach out to support them as needed. Crowd-Source Resources. You could create a space for students to share resources with the class. You could use a tool like Padlet and set it up with column headings, which you can co-create with students or set ahead of time. For example, you might use categories like “Resources for De-Stressing” or “Things that Made Me Laugh” or “Strategies That Helped Me Learn at Home.” You can also use this as a chance for students to play with the various types of responses you can add to a Padlet. Encourage them to try adding audio or video or a drawing when relevant. Whatever activities you choose, I’d love to hear how it goes! Feel free to share below or in our Time for Teachership Facebook group. Our sharpened focus on issues of equity in education in the time of COVID-19, has raised many questions such as: How can we improve educational equity? What policies are perpetuating inequity? How can we replace them with policies that promote equity? How can we systematize equitable practices so they are not “one-time” strategies? How can we measure this? (In other words, how will we know if we are successful?) And with all the things that are uncertain, leaders are asking: What is within my locus of control? As a leadership scholar, my response to each of these questions is: shared leadership. I prefer this term to the more popular, “distributed leadership” because while distributed leadership is inclusive of teachers in leadership, it stops short of sharing leadership with students and parents. Shared leadership enables us to be inclusive of all stakeholder groups. Additionally, the word “shared” is centered on what Mary Parker Follet calls “power with,” whereas “distributed” maintains a hierarchical sense of “power over.” How can we improve educational equity? We cannot answer the question of how to improve equity by ourselves. I can suggest some places to start, but to address the needs of your specific community, you’ll need to ask the various stakeholders in your community. Shared leadership asks us to listen more than we talk. So, the first step in identifying how your school can improve equity is identifying who can provide answers. That list will include families and caretakers, students, teachers, and perhaps members of the larger community. What policies are perpetuating inequity? Encouraged by this year’s renewed societal commitment to eliminate institutional racism, educators have been increasingly focused on identifying and dismantling the policies that perpetuate educational inequity. Many schools are starting to take a hard look at punitive discipline policies, problematic dress codes, and how students are graded. However, even if we can identify policies that need to be changed, we need to include stakeholders in the creation of whatever policies replace the old ones. How can we replace inequitable policies with policies that promote equity? Research tells us organizations benefit from improved decision-making when multiple stakeholders are involved in the decision-making process (Kusy & McBain, 2000). If we want to be more equitable, we need the students and families who have been historically marginalized by inequitable policies at the policy-making table. The policies are important, but how they are created and whose voices are involved in the creation process is how we ensure new policies don’t continue to perpetuate inequity. How can we systematize equitable practices so they are not “one-time” strategies? Creating shared leadership structures that inform the school’s decision-making process is a powerful way to systematize the school’s commitment to equity. If each time a policy is created, parents, students and teachers are part of the process, this communicates to stakeholders their voices are truly valued. Furthermore, given all the uncertainty of this school year, how decisions are made is one thing that is within a leader’s locus control. The decision to share power is a powerful step towards educational equity. Logistically, researchers have identified several things to consider when creating shared leadership structures: Embrace radical collegiality. Fielding (2001) defined this term in relation to students, but it’s useful for our work with families and caretakers as well. Basically, it refers to the idea that educators learn and become more effective when they see students (and families) as partners and they share responsibility for student success. This mindset is critical to the success of any organization rooted in shared leadership. Build a representative leadership team. Research has found groups larger than about 15 members can become unwieldy and ineffective (Calvert, 2004; Pautsch, 2010). As much as possible, stakeholders should be represented equally, with a slightly higher percentage of students to reduce the ratio of adults to students, which has been known to overwhelm and thus, silence students (Osberg, Pope, & Galloway, 2006). Clarify the governance structure. Explicitly state how and to what extent power is shared. Identify which types of decisions will be made solely by the school’s administrator(s), and which types of decisions will be shared. Clarify what is needed to move forward with a decision (e.g., majority vote, unanimous agreement). Determine leadership team members’ responsibility to communicate with the stakeholders they represent (e.g., weekly, only to get feedback on major policies). For example, the leadership team may draft a new policy and want to get feedback within one week from all stakeholder groups so they can vote to approve the policy the following week. Use stakeholder research to inform decisions. Decisions made by the shared leadership team should be based on data. To address the question of how we measure equity—sometimes, we will look at student data like grades or test scores. Other times, that data will be survey data in which stakeholders share their degree of belonging in the school or the extent to which they feel their voice is valued. Students may self-report their level of engagement in class. Members of the leadership team should receive the support needed to enable them to communicate regularly with the stakeholders they represent. This could take the form of tech tool training so all members are able to create and send out a survey using Google Forms or to communicate asynchronously using an app like Voxer or an LMS like Google Classroom. Meet consistently. Meetings should be held consistently, at the same time and in the same place (whether that’s the same physical location or the same virtual room) if possible, to avoid confusion that may exclude members from participation in the meeting. To help you get started in thinking through all of these considerations, I made a worksheet with a list of relevant questions. You can use it to guide your thinking as a leader or prompt discussion among stakeholders or in your leadership team! Two leaders who have informed my coaching and leadership practice are Ella Baker and Mary Parker Follet. Ella Baker, a staunch supporter of shared leadership during the U.S. civil rights movement has said, "I have always thought that what is needed is the development of people who are interested not in being leaders as much as in developing leadership in others." Follet (1924) addressed leaders’ fears that power was a zero sum game, by writing, “first, by pooling power we are not giving it up; and secondly, the power produced by relationship is a qualitative, not a quantitative thing” (p. 191). She later wrote that sharing power is generative, that confronting and integrating different ideas “means a freeing for both sides and increased total power or increased capacity in the world” (pp. 301–302). I’m excited to hear how your shifts towards shared leadership increase capacity and equity in your schools. As a teacher, it was never comfortable making a mistake. Whether I made an assumption about student behavior, answered a question incorrectly, or mispronounced a student name, the guilt and shame of making that mistake hurt. Those feelings of guilt and shame never fully went away, but I became more comfortable with apologizing and seeing the opportunity to recognize my mistakes as a chance for growth. This year, as I have grown my business, I’ve been figuring out how to do the same in a different context. Being in the public eye is not comfortable for me. I’m not a big fan of social media. I’m an introvert whose ideal weekend is reading a book at home on the couch. However, we miss out on a lot when we remain in our comfort zones. This year, I’ve received more critical feedback than ever just by virtue of having a larger audience. While some “feedback” has been unhelpful anger about the goal of educational equity, far more feedback has been immensely helpful critique from this brilliant community of educators. While I’m still working on releasing the feelings of guilt and shame that linger way beyond the day I receive the feedback, I have to say, I am truly grateful for the time educators have taken out of their busy days to share how I could do better. I think about how much courage and energy it takes to read something, feel frustrated by it, and then decide not to discount the author, but actually send an email to share that frustration and give me a chance to do better. I also think about the trust required to take the risk of providing feedback—the belief that the message will be heard, that it will result in change, that it will not result in anger-fueled backlash—and I am profoundly grateful for that trust. I will continue to make mistakes, and I will continue to work on my response to critical feedback. If I cause harm, I want to apologize and also commit to doing better moving forward. (A book that has helped me think about apologies is On Apology by Aaron Lazare.) I will continue to do the work to learn about racial, gender, sexual, and dis/ability justice. I will continue to invite feedback from educators. I also bring all of these commitments into the virtual teaching space as I prepare for the Fall semester. This semester, my class will be fully remote, and so I’ll need to establish that trust and co-construct (with students) a community focused on growth, not perfection. I recognize that building this community at a distance may look different than it did teaching in person, but it is still possible, and it is, perhaps, more important than ever. As many of us learned during Spring 2020, holding class in virtual spaces comes with additional challenges like having family members or others watch you teach. I know many teachers are concerned about students sharing recordings of live classes and being under scrutiny for mistakes made during class. I have no magical solution to this concern. I’ve worked with teachers this summer who have reported such a thing happened to them this spring. However, it makes me think about when I taught high school and we had a standing invitation to any family members or caretakers who wanted to shadow their children in their classes. While this was a bit nerve-wracking, I appreciated the oversight. I wanted that accountability, not as a “Gotcha, you’re fired,” but as a learning opportunity to share feedback like, “You never called on my child when she had her hand raised,” or “My grandson struggled with the assignment and didn’t know how to get help when he needed it.” A family member courageously delivering feedback to me with the trust that I will listen and do better? I want as much of that as I can get. I don’t say this to discount the real fear of recorded classes being misused in harmful ways or to pretend the guilt and shame doesn’t sting, but to help us frame our thinking about how we view productive critique when we make mistakes. To increase the likelihood of productive criticism in my own class this year, I want to start the semester by framing the learning journey as something we’re all on together, myself included. I want students (and their families) to know I see them as partners in the work, and I want to create space for members of the class community to courageously and without fear of reprisal share critical feedback if I made a mistake, omitted a marginalized perspective, or caused harm. I was recently on a webinar in which Dr. Ibram X. Kendi shared a powerful analogy about diagnosing a problem. He said when his doctor diagnosed his GI symptoms as Stage 4 colon cancer, he was immediately resistant. “Not me,” he thought. I don’t drink; I don’t smoke; I work out. Being an antiracist scholar, he drew a parallel to people’s defensiveness in being told their actions were racist. He said it’s the same with the doctor—diagnoses aren’t shared to hurt anyone. Diagnoses are delivered with the intention to heal. I found this analogy incredibly powerful in thinking about the mistakes we make as educators and the mindset required to view critique as opportunities for growth. If it helps to track your growth over time so you can see the benefits of listening to criticism and growing as a result, I’ve made a Mistakes as Growth worksheet for you! Here’s to a new academic year filled with learning, healing, and growth for all of us. Last week, I took a week off of the blog for the first time since December. It was my attempt to practice boundaries and self-care to continue the collective care work. The day I was scheduled to take off? I worked all day. My rational brain understands taking the time to rest and recharge is necessary to sustain my energy for the important work we do, but there are several mindsets I continue to struggle with—mindsets that hold me back from putting this understanding into practice. In this post, I want to share a behind-the-scenes look at the struggles that often prevent me from striking a work-life balance. I hope you do not recognize these mindsets in yourself, but if you do, you are not alone. Side note: I intentionally use the phrase “work-life balance” because while I think there are interesting elements of Struggle #1: I Tell Myself “I Can’t Afford the Time Off” Being my own boss, I have the great privilege of setting my own schedule. However, I’ve found I rarely let myself take time off. I tell myself I can’t press pause on the things I have going on. Last week, for example, I took a week off of blog writing, which freed up about a day’s worth of work. I scheduled my day off. One day. I had been physically ill for several weeks, I hadn’t been sleeping or eating well, and I still couldn’t value the importance of my mental and physical health over the tasks that could wait another week or take a week off. The rational part of my brain says, “The late night comedy shows I watch have been taking time off. I should follow their lead!” But I tell myself my work can’t wait. Ha! I’ve been learning more about white supremacy culture, and the sense of urgency that I need to get everything done now and do it all perfectly are two aspects of white supremacy culture. Maintaining these mindsets of urgency and perfectionism actually inhibit my ability to learn and grow. I want to learn and grow; therefore, I need to take the time to be well enough to recognize learning opportunities when they present themselves and be well enough to dig in and do the work to grow in those moments. Struggle #2: I Can’t Put My Brain in Vacation Mode That one day off? I ended up working a full 10-hour day. Something came up that needed to be done, but I know myself. I would have been thinking about work most of the day anyways. I struggle to turn my work brain off. In some ways, this can be helpful. I like randomly thinking up ideas for new units when I’m going for a run or doing something non-work related. That’s a part of work-life integration I can get behind. But, I struggle to simply “be,” and I recognize that’s a problem. It has always been a struggle for me. I’ve gotten sucked into the fast-paced, work-centered culture we live in. Recently, I’ve been scheduling 15 minutes of mindfulness into each day. I use the Stop Think Breathe app on my phone to spend some time paying attention to my body and my breath, and I have created a separate work “log in” on my laptop to create a digital “door” to my virtual office space. My identity has always been tied to my work, and I don’t think that, in and of itself, is harmful. It’s part of that passion and drive I feel to do the work I do, but when I don’t give myself the proper space and time to relax, it also takes a pretty big mental and physical toll. I’m still working on overcoming this struggle, and I don’t think it’s realistic to expect I’ll never think of work when I’m taking time off, but I do think it’s possible to get to the point of recognizing the work thoughts as I have them and perhaps writing down ideas or reminders if I need to, so that I can stop fixating on work and let the thoughts leave my mind until the next work day. Struggle #3: “I Must Be Constantly Available” On my days off, all I want to do is stay very far away from my computer because my computer—as a result of working from home in a one-bedroom apartment—is the physical representation of my workplace. I know I feel better when I can completely separate from my workplace, but any time I step away, I feel like I am somehow failing the amazing community of educators who may be counting on me for a quick response to an email or a Facebook message. This was the same mindset I struggled with as a high school teacher—what if my students are emailing me with a question and I don’t answer it until tomorrow? I thought that would make me a total failure as a teacher! (I hope you’re able to laugh at me because you see how ridiculous this idea is, but I really believed it.) What helped me with this was seeing my principal model these boundaries. She would let everyone know they needed to go home and be home and there was zero expectation of checking email because she would not be checking her email. A few times over the years, I was frustrated that she was unavailable, thinking I needed an immediate answer to something, but in each of the situations I thought required an immediate response, it didn’t. I was able to adapt and make it work. I realized that her insistence on email and vacation boundaries were far more helpful to me than a quick response to a single question. She was modeling healthy boundaries. Modeling Healthy Living Many of us integrate SEL practices into our classes because we know students need to be socially and emotionally well to thrive. This has become even more relevant during the pandemic. This notion of modeling is really helpful for me—if I won’t push myself to be well for my own sake, I will do it to help others. So, what can we model for students and fellow educators? Urgency & Perfectionism. Flexible deadlines helped me model for students that while we need to get things done, I didn’t want my students having a mental breakdown because they were so stressed about a due date. Some assignments, like public presentations, had a deadline that could not be altered, and students knew they needed to meet it. Other assignments that were submitted to me had somewhat arbitrary deadlines that I set, and I could afford to be flexible if it helped a student’s mental wellness. I’ll be writing more on perfectionism in my next post, but as a teacher, I found I had a great opportunity to model how to overcome perfectionism. First, when I would make a mistake (because of course I would, I’m human), I would apologize, and I would let students see that being perfect is far less important than how you respond when you make a mistake. Vacation Brain. Many of our students (two-thirds by age 16) have experienced some form of trauma. Taking just a minute or two of my class each day for mindful breathing helped me and my students build our capacities to simply “be”. One day, after doing our 30-seconds of breathing time, a student thanked me and said “I never have time to just breathe.” I saw myself in her comment, and I realized we all needed to continue this practice. Another way I tried to support students in embracing vacation brain was not assigning homework over vacation. (Some students liked to use vacation time to get a jumpstart on projects, so I would often share what we would be doing when we returned from vacation, so students could do work if they wanted, but there was no pressure to complete any assignment for the first day back.) We all need that break. Being Constantly Available. I was fortunate to have an administrator who modeled healthy boundaries for me and respected the ones I set for myself. As a teacher, I realized, in setting and sticking to boundaries of my own, I could model healthy practices for my students in the same way my principal modeled this for me. My students grew used to the fact that I didn’t respond immediately to email, and they learned to figure things out for themselves or wait until we were back in class to ask. For this last piece to work effectively (in other words, to prevent students from experiencing high levels of stress while waiting on my response), I had to be flexible in my deadlines for assignments and make space during class for students to work on whatever they needed to work on. This flexibility was necessary for the boundaries to work, but it came with another host of benefits—opportunities for more 1:1 or small group meetings with students, additional chances for me to give in-the-moment formative feedback, and students generally experiencing less stress and more agency regarding their work. Personally, I often struggle to overcome these challenges because I add too much to my plate. Saying “No” is difficult, but I will continue to work on doing it better. In fact, I’d like to shift my focus from what gets a “No” response, to what, as a result of the "No"s can finally get a “Yes”. Jenna Kutcher says when she says no, she frames it by saying: Here are my current priorities, and I have to say no because it doesn’t fit with my priorities at this time. I like that frame because it provides a rationale (although, to be clear, we don’t need to rationalize our “No”s) and we are also modeling for others how they can say “No” themselves. For reminders about this, I’m re-sharing my boundary reminders printables. Click the button below to grab them and put them in your workspace. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed