|

As we continue to consider the opportunities we have to try out student-centered approaches to instruction while teaching virtually, I want to talk about student goal setting. Research tells us that when people set ambitious goals, they are more likely to achieve them than smaller goals, and they are more likely to prioritize “goal-relevant” activities over “nonrelevant” activities to seek new knowledge (Locke & Lathan, 2006). I would love for my students to achieve ambitious goals they set for themselves, and I certainly would love for students to be motivated by their goals to learn more! That’s a teacher’s dream. Research also tells us that writing goals down significantly increases the likelihood we’ll achieve them, and sending weekly progress reports for accountability makes it even more likely we’ll get to that finish line (Matthews, 2015, accessible on this page). These research findings feel particularly translatable to the classroom, as we could have students write their goals and submit a reflection on their progress towards the goal each week. Sounds great, right? The question is: How do I support students to set high quality goals? Goal setting can be incredibly effective, but most students—even most adults—are not prepared to write effective goals. There are a few things I’ve found helpful in supporting students to set quality goals: using a SMART goal framework, lots of modeling, and an intentional inclusion of steps to reach the goal. SMART Goal Framework SMART goals are: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. I’ve found relevancy to be the least problematic component. Students usually set goals related to what we’re doing in class. The concept of setting a deadline by which to meet the goal is usually fine with students, but the achievable aspect of the chosen time frame is more challenging. Goal specificity usually comes with practice, but this will take some modeling. In my experience, the most challenging element of SMART goal setting for students is setting measurable goals. This requires lots of modeling and often direct support early on. A peer review of goals can also be helpful. Before students finalize their goal, they can share it with a peer and ask: How would you know I met my goal? If the peer has no idea, the student knows it is not measurable. (Of course, you can do a peer review for any or all of the aspects of a SMART goal.) Lots of Modeling To support students, we can set our own life/teacher goals. I am thinking specifically of two amazing teachers I coached who shared personal exercise goals with their students (i.e., I will run x miles keeping a pace of x minutes per mile; I will walk for x number of steps this week) because they were examples of goals that were specific and measurable. You could also set class goals together (e.g., we will spend x minutes on mindful breathing this week). When you’re first getting started with student goal setting, it may be helpful to offer sentence starters or a SMART goal setting template to help students formulate high quality goals. I also find it helpful (if students are okay with this) to share a few student-written goals and review them as a class, offering suggestions to strengthen a particular aspect that’s unclear or highlighting how each aspect is present in a high-quality goal. Inclusion of Steps to Reach the Goal In my experience, the #1 reason student goal setting is ineffective is the lack of follow-up. Students may set a wonderful SMART goal but then have no idea what to do to reach the goal. This problem can be addressed by including the steps students will take to reach their goal as part of a goal setting template. If there is a designated space for this, students can spend some time really thinking about what they can do to achieve the goal they set. We can also model and provide examples of what steps students can take to move towards their goals. One way to support students in selecting relevant activities for this part of the template is to provide an activity bank for students. Then, students can circle, highlight, or select from that bank. Over time, this scaffold can be removed or transitioned to an anchor chart on the wall which students could reference if needed. I love the idea of co-creating an activity bank with students by asking them how they might reach their goals and adding to an anchor chart as they share. To help you jumpstart student goal setting in your classroom, you can use my goal setting template by clicking the button below. One final note on student goal setting. I’ve worked with many teachers of younger students who have had success with this activity (and with the above template). If you teach young kids, know they are definitely capable of quality goal setting; it will just require a bit more scaffolding.

0 Comments

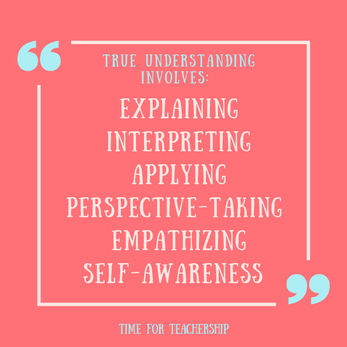

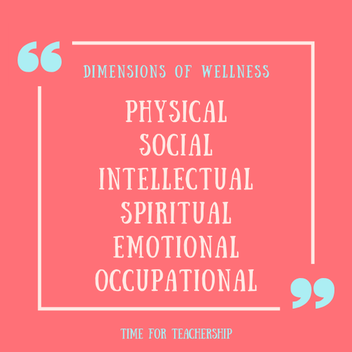

This post continues the series of blog posts on the opportunities our education system has to positively transform during this pandemic to better serve the needs of our students. Today, I’m diving into a differentiation strategy called: What I Need (or “WIN”) Time. The basic idea is exactly what the title says—helping students get what they need when they need it. Each of our students are unique individuals who learn at different paces and in different ways. We know that talking at the class for the entire lesson and then handing each kid a textbook doesn’t work, because that one-size-fits-all practice is how we ended up with the egregious educational inequity we have today. Recognizing the need for differentiation, let’s think about how to set up WIN time… Activity Options First, students need to have a few options for what to do during this time. Of course, some can meet with you, but while you’re meeting with a small group, what is the rest of the class doing? I encourage you to check out my post on free resources for self-paced learning, which serve as excellent low-prep activities for students to use independently during WIN time. Student Choice Next, to promote student reflection and ownership during WIN time, it’s best to have students choose what it is they need to do during this time. At first, you may find it easier to tell students where to go based on what you think they need, but if you continue to do this once students are familiar with the process, you’ll miss opportunities for student self-assessment and reflection. Pre-work: Class Data Dive Of course, students may need some support in determining how to make informed choices during WIN time. I like the idea of creating a lesson just for this purpose. During this lesson, you may want to guide students through recent assessments and help them identify which skills are strengths and which are areas for growth. You can teach them how to read and make sense of your feedback to determine what they need to do next. Pre-work: Self-Assessment I also love the idea of combining a self-assessment activity with WIN time. Having students self-assess their mastery of a topic or skill on Marzano’s 1-4 scale is one way for students to determine the degree to which they have mastered a piece of content or a specific skill at a given point in time. This approach also promotes the concept of mastery as a progression. Knowing mastery takes time and everyone moves through the stages of mastery at different speeds depending on the skill normalizes the idea students have not yet mastered something and need more help. The video at the top of this page is a great example of how this could look in a classroom. In a Virtual Learning Environment In virtual spaces, WIN Time can be done on live class calls (via Zoom or Google Meet), asynchronously, or a combination of both. On a live call, you may have students working independently while you go into a breakout session with a few students. Asynchronously, you may provide a list of resources for students to engage with (perhaps organized by Marzano’s mastery levels), and they complete those tasks by the end of a specific time period. A combination might look like an asynchronous task list or choice board with an option to meet with the teacher in a small group. If students choose this option, you could then hold a live group session over video chat (or by phone if a student doesn’t have video access). As with all of these examples of instructional opportunities, WIN Time can help your students now—by helping struggling students catch up and giving other students a challenge—and it will continue to help differentiate instruction for your students in the physical classroom. Quality differentiation is a difficult undertaking for teachers regardless of where the learning is taking place. This strategy is one way to differentiate effectively. In my last post, I started talking about the opportunities we have as educators and collectively, as an educational system, during this pandemic to be able to make some positive shifts in our instruction. In the last post, I discussed assessments that involve application or creation and the opportunity to spark more intrinsic motivation in a time when we may not be grading student work. I ended by promising to address how we might amplify students’ intrinsic motivation to learn. One exciting opportunity for students to have a voice in what they learn is Genius Hour. It’s also been called “20% Time.” This 20% comes from Google’s “Innovation Time Out” practice of having employees dedicate 20% of their workweek to a project they are passionate about. Gmail was created during this 20% time! This idea has since been embraced by educators and translated into a classroom practice. In short, students get one day a week or 1 hour a day to work on a passion project of their own. This is an incredible opportunity for students to find intrinsic motivation for learning. When I taught high school, I tried Genius Hour on a large scale. I created a semester-long unit in which students designed and completed their own project-based units. It was a lot of work, but it was really cool. Now, I’m not saying you should do this, but I wanted to share some things I learned from this experience as well as a free resource you can use to support students to get started. Learning #1: Students may initially struggle with free choice I was shocked that many of my students’ initial reactions were a variation of, “Just tell me what to learn.” I realized older students have been “doing school” the same way for a decade! To have one teacher all of a sudden interrupt that was a shock to their systems. They came around eventually, but it took a lot of modeling (What might this look like?) and scaffolding (How exactly do I design a unit?). This week’s freebie is the set of student worksheets I used for the first days of the unit. Click the button below to get it! The free planning doc includes: initial brainstorm questions students filled out individually; an outline of the proposed project (unit) to be completed by the group or individual (depending on whether they chose to work alone or with a partner(s); and two examples of a completed outline—one for a Science-based unit and one for an ELA-based unit. Learning #2: You can require alignment to course standards At first, I thought if I require students to meet specific parameters for this project, it’s erasing the students’ voices in the project. Then, I realized, students actually wanted and needed some direction (especially for our full-time, 4-month project.) So, I included a section in the outline (see freebie above) for skills, and I told students they needed to select skills from the appropriate grade’s ELA standards. I gave students a choice of which standards they wanted to include, and I made a cheat sheet for them with all of the standards, examples of each standard, and a “difficulty” rating (based on my opinion). This scaffolded support helped, and students were able to thoughtfully choose to work on skills that not only fit with their project idea, but also that met a need they had as learners. Students impressed me with their ability to deeply reflect on their mastery of the standards and choose skills they personally needed more time to practice. Learning #3: It’s okay to ask for help This is a valuable life lesson I’m still learning, but for this project, it was essential. I had 100 students tackling over 50 topics, most of which I was completely unfamiliar with. So, I emailed some friends as well as the staff at my school, shared the list of students’ topics, and asked if anyone had any contacts with people in these industries. I also encouraged students to reach out to their own contacts or find people online. I am still blown away by the manner in which people showed up for our kids. One student established a professional photography contact who gave her a used camera! Of course, not every student had a professional from their specific field as a mentor during their project, but teachers and adults who simply wanted to be a part of the project offered to act as a general, independent learning mentor. If you’re interested in starting a project like Genius Hour, I suggest giving students a few questions to think about to support them in choosing a meaningful topic and goal. Feel free to use the template I shared! Don’t be afraid to add in requirements for standards, even if it’s as simple as: I need to see you analyze something by the end of your project. Finally, reach out to your contacts and see who’s willing to support kids during their exploration of new topics and their self-exploration of how they learn best. In the opening of this post, I framed this as an opportunity. It’s something we can test out in the short term while we’re teaching in virtual spaces, but we can also use Genius Hour once we’re back in brick and mortar classrooms again. Sparking students’ motivation to learn is beneficial in all spaces! This pandemic has asked a lot of educators. Transitioning to remote teaching at a moment’s notice is highly difficult and overwhelming. To be clear, no one is going to make an emergency transition like this perfectly. In fact, because this is new, teachers have been forced to teach in innovative, nontraditional ways. Some of these innovative pedagogical practices may have long-lasting positive effects on student learning. That’s right, I believe our education system has an opportunity for immense growth amidst all of the chaos. This post is the first in an “Opportunity” mini series where I’ll be discussing ways educators can test out ideas and strategies they might normally feel hesitant to try. But, given the “whatever works” attitude many of us have had to adopt in this emergency situation, this may actually be a good time to try something new. Opportunity #1: Rethink Assessment Teachers who typically assign multiple-choice quizzes or tests as their primary form of assessment may now be worried about students being able to cheat (i.e., look up the answer) while taking the quiz from home. One way around this is to create a task in which students cannot cheat. Try an open-ended question where there is no correct answer. Even better, create an application project in which students have to apply the information they learned to solve a problem or transfer the information to a novel situation. Another big mindset shift to consider is whether it’s actually bad practice for students to look up answers. Tests are assessments that really only exist in academic spaces. Sure, recall of factual information is helpful in life and in many careers, but many projects that adults are required to complete offer time and space to find answers to questions of which they are unsure. Just the process of looking up the information is helpful for students to learn, and by finding the correct answer, they have one more exposure to the content. One solution might be to tell students quizzes and tests are “open book” and tell them why—this is typically how life works. I need you to know this, so do what you need to do to find the answer. The other shift here is thinking about what we are asking of students when we ask them to answer multiple choice questions as a summative (or some formative) assessment. What do their correct answers tell us about their capabilities? At best, they tell us students can memorize information. Multiple choice test results do not tell us what they can do with that information. Can they apply it? Maybe. Maybe not. A professional in your discipline will need to apply that knowledge, not simply remember facts. Something you may consider doing when thinking about designing assessments is to ask: What does a professional in this field need to do? What will I know my students are able to do when they complete this assessment? Where would I find the skills they are demonstrating in this assessment on Bloom’s Taxonomy or Webb’s Depth of Knowledge chart? These ideas are valuable now that we are teaching remotely, but they are also incredibly valuable for the long-term as well. Application-based assessments and asking students to demonstrate higher-order thinking skills is a great curriculum design goal at any point in time. Opportunity #2: Rethink Grades Many schools and districts have prohibited grading students based on content or assignments shared in virtual classrooms. There’s a great reason for this. We cannot punish students who do not have access to the requisite technology to engage with online learning activities. However, a concern is that students who do have access to connected devices will not attend virtual classes or complete assignments if they are not being graded. Students have been trained their entire educational careers that they need to work hard to get a good grade. By the time they reach high school, this idea is deeply ingrained. The grade is what we hold over their head—the proverbial carrot (or stick). The problem with students only doing things for a grade is the lack of intrinsic motivation to learn. It’s interesting to think that grades may actually be inhibiting student learning. It deeply saddens me to hear students say they only care about the grade. I often wish I could get rid of grades all together to help students just focus on learning as much as possible because learning is valuable all on its own. That’s the opportunity we have right now! In many places, grades are off the table. Now, we just need to reignite that inner drive to learn for the sake of learning. (That’s a tall order, so the next several posts will address how we might do this.) In your school or district, you may still be required to give grades right now, and eventually we will all return to our routines and grading will be required. So, how does this apply in the long term? Reducing the number of grades helped me a lot. Sharing qualitative feedback in place of grades on formative assessments or classwork helped students develop more intrinsic motivation for daily assignments because the only official grade they received was on their final assessment. For teachers who work in schools that require a minimum number of grades, you will likely need to comply. Although, you may consider asking your administrator if feedback could be given in lieu of a formal grade. (Often administrators have a minimum grade requirement as an indicator that you, the student, and the student’s family can speak to the student’s academic progress. I know many administrators who are open to the idea of conveying that knowledge in ways other than grades.) Another option is if a grade is required in the short-term, ask if that can be overwritten by summative assessment grades when calculating the grade on each report card. These shifts may feel really big and overwhelming at this time of already high overwhelm, and if this is how it feels, don’t put more pressure on yourself. These posts in the opportunity series are not intended to be a list of things you need to add to your already overflowing to do list. These are merely positive spins on a tough situation that you can choose to try if you want. I’m excited to hear what comes from your innovative experiments in the areas of assessment and grades. Please share with the community in the comments section or on our Time for Teachership Facebook group! Earlier this week, I wrote about McTighe and Wiggins’ Understanding by Design (UbD) framework for backwards planning, which asks educators to answer the questions: What do you want students to achieve? How will you know students have achieved these goals?; What learning experiences will best support them to get there? The previous post addressed the first two questions. (If you haven’t already read that post, go back and read that first.) This post will address the third question. By answering questions one and two, we know where we want students to end up, and we know how we will assess whether (or to what degree) they made it there. Now, we must think about the learning experiences that will help students acquire content and skills, make meaning of the information in a particular context, and then transfer their understanding and skills into a new context (ASCD). Let’s consider how each of these three components (acquiring content and skills, making meaning, and transfer to a new context) might show up within a unit. How do I help students make meaning of the information? It’s helpful to situate content information in a particular context as much as possible throughout the unit, and that starts with a strong, contextualized hook. I like to use hooks that are relevant to students’ lives. For example, this might look like watching a documentary or news clip about a current event that addresses a core understanding of the unit or posing the essential question as it pertains to their personal lives (e.g., “When, if ever, should violence be employed to secure human rights?” may be initially discussed as it relates to an individual fighting to defend theirself or someone else). Throughout the unit, I like to use case studies to explicitly situate information within different contexts. For example, if I’m using the essential question above on violence and human rights, I might design several historical situations in which violence either was or wasn’t used during the course of a human rights struggle (e.g., examples of non-violent resistance in contexts like the U.S. during the civil rights movement of the 1960’s and South Africa’s anti-apartheid protests and also violence forms of resistance in both of those contexts). To make meaning of these case studies, I would encourage students to use the information from each case study to make a claim in response to the essential question and defend it. This activity could occur in the form of small group discussion or a class-wide discussion like a Socratic Seminar. How do I help students acquire the knowledge and skills they need to be successful in this unit? When our end goal is deep understanding and mastery of transferable skills, we need to give students time to develop both. Which means, our unit may need to be longer than we initially think it should be. Although we may think, “I don’t have time for long units!” longer units enable students to go beyond a mere surface-level understanding and retain that deeper understanding for a longer period of time. So, make sure your unit is an appropriate length for students to move through the phases of learning (the initial exposure, the practice, and the mastery). I would also try to vary the types of content delivery and types of experiences in which students are engaging throughout the unit. Try to include a variety of activities such as: interactive mini lectures or videos for content delivery, textual analysis, simulations (although, be thoughtful about what to simulate) and opportunities for discussion and collaborative learning. Providing time during the unit for students to work on different things to fill content or skill gaps (or extend their learning beyond the whole class lessons) is also important to ensure each student gets what they need. How do I ensure students are able to transfer their learning to new contexts? This is exactly what the summative assessment task at the end of the unit should be— an opportunity for students to apply (transfer) their content understanding and skills from the unit in a new context. This assessment is how you know the degree to which they achieved the goal. If you’re already at the point of planning the day-by-day learning activities, you’ve likely already planned this summative assessment. If you haven’t (or if you did, but it doesn’t ask students to transfer their learning in a novel context), go back and create or adjust your summative assessment now. The summative assessment should not be the first time students are asked to perform this difficult task of applying their skills and knowledge in a new way. So, once you have the summative assessment set, work backwards and try to think of other contexts (not the same one as the summative task) you might ask students to engage with during the unit as a practice application. Consider scaffolding these formative assessments to gradually build up students’ individual capacities for application. For example, you may first pose a problem in context to the whole class, so you can help students figure out how to approach the task, highlighting various strategies you see students use. The next time you present a problem in a novel context, have students work in small groups or with a partner so they don’t have to work on their own just yet. Finally, have them perform a similar task in a different context on their own. To be clear, these formative assessments do not need to be in-depth, they might just be a discussion, nothing written, or maybe just some quick notes on a piece of chart paper. You don’t need students to complete the final project three times in full, just expose them to the task of problem-solving in new contexts. If you would like a template to guide your planning of unit learning activities, click the button below to get my free Backwards Planning Template! Also, if you a fan of conrete examples, this Cult of Pedagogy podcast episode and corresponding blog post shares one instructional coach talking about how her teachers backwards planned a PBL unit. It focuses mostly on McTighe and Wiggins’ first two questions, but the speaker makes clear how valuable those steps are to ensure alignment with the third question of day-to-day learning activities. Some schools already know they are not going back to in-person teaching until next school year. Others are still unsure if they will return to classrooms to finish out the school year before summer break. Regardless of whether you’re planning for the last few weeks of the school year or you’re already thinking about next year, it’s helpful to have an approach that ensures you keep the end in mind when you plan. This ASCD white paper summarizes McTighe & Wiggins’ Understanding by Design (UbD) framework for backwards planning. Simplified, it’s basically: What do you want students to achieve?; How will you know students have achieved these goals?; What learning experiences will best support them to get there? So, with that in mind, let’s consider what you want students to achieve by the end of the year. Ask yourself: What are the most important things I want my students to know or be able to do by the end of the year? A couple of quick notes for teachers backwards planning the rest of the 2019-2020 school year: If your answer is related to something you already began teaching earlier this year, your plan for the last few weeks of school may be to put the finishing touches on that particular skill or content understanding. If your answer is related to new content or a new skill you have not yet taught this year, try to be realistic in how much content you’ll expect students to understand or to what degree students will be able to hone a new skill, given the short window of time you have left. I always emphasize depth over breadth. Choose 1-2 key content understandings or 1-2 skills (more or less, depending on how much time you have left in the school year) that will be transferable to next year’s content or to other disciplines. For example, I believe the skill of being able to analyze was one of the most transferable skills for students across content areas. It’s also one of the skills my students struggled with the most, so I would try to focus my attention on that. If we are getting really particular here, I would then write out a definition of what mastery of this skill or content understanding will look like. I do this because I think it is helpful for me as a teacher/curriculum designer and my students to understand exactly where we are going. I like to do this using one of these rubric templates. Once you have defined mastery for whatever it is you are teaching, you will then need to decide how students will demonstrate mastery via an assessment task. ASCD explains what McTighe & Wiggins say these summative performance tasks should include, stating the following: When someone truly understands, they

They also suggest an essential question to engage students in making meaning of content within a particular context. This question will drive your lesson planning and students’ focus during the unit—every learning experience should be aligned with the goal of helping students address the essential question. An additional note on alignment: it is important to align your instructional priorities (the goals you stated as a result of the previous question) with your assessment. If a major content understanding or skill is not assessed, you may want to ask yourself why you’re teaching it. Remember: less is more; depth over breadth. Once you have decided on your final performance task to assess student mastery, you can then go back and insert some formative assessments, like checkpoints along the way, to make sure students are mastering the smaller components or steps within each major conceptual understanding or priority standard/skill in the unit. After answering these first two questions (what you want students to achieve and how you will know they achieved it), you will need to plan out the learning activities you’ll use to help students acquire the content and skills. This third question deserves it’s own post, so to be continued later this week… Ensuring students get the exact content they need when they need it is difficult when you see them every day in the classroom. It’s even more difficult when you don’t see them every day, and each student has different degrees of time and technology access to be able to engage with the content you share. As teachers, we may not be able to get a laptop and WiFi into the homes of each student who needs it right now, but we can share some resources with students who are able to engage in self-paced learning. I have heard a lot of school districts say, due to inequitable access to technology, teachers should only be posting review material. The students who could benefit from this are the ones who have been struggling to catch up, perhaps performing several grade levels below where they should be, AND they have access to quality resources they can use to catch up. By quality resources, I mean (where possible) the resources are dynamic and adapt to what the student needs. Furthermore, if the student struggled to understand the content the first time you delivered it, there may be a benefit to getting the same resource again (e.g., recorded lecture to re-watch, worksheet to complete again), but they are more likely to benefit from a new way of explaining the material or a new type of engagement with the content. I recognize this is not realistic to ask a teacher to create 30 or more iterations of the same content. As educators, we do not have the time to create all of this from scratch, nor should we, because, again, we likely need people (other than ourselves) to deliver the content in a new way. So, the question becomes: Where do I find those kinds of resources? There are so many resources out there, and since many platforms are freely accessible for the duration of the coronavirus pandemic, there are even more than usual available. I curated a short list of resources for each subject to reduce the time it would take for you to sift through hundreds of possibilities. I offer a handful of sites for several subjects and prioritize resources that have always been free, so that after we return to in-person classrooms, you may continue to use these resources at no cost. I was also strategic in choosing resources students would be able to readily engage with. (There are many resources, such as Facing History, that are full of great stuff, but often require an educator to do some extra planning to frame or deliver the content. Therefore, those types of resources that are made for an audience of educators were not included in this list.) Once you’ve gone through the list of resources, you may wonder: How do I use these resources in my instruction? The answer depends on the type of resource, but I’ll share a few examples of how you might use these resources in your classroom (your virtual classroom now and your physical classroom in the future). Topical videos. Let’s say you want students to review a specific piece of content. You may want to share some options with students, so they can choose one resource (or multiple resources) with which to engage. You might decide to offer three choices on a mini choice board: a resource you already gave them (to watch or complete again), a new topical video someone else created from a site like Khan Academy, History.com, or Discovery Education, or a student-created mini lesson (which your students who have mastered this topic could create using a creation tool like Flipgrid or Adobe Spark Video. Learning pathway programs. Perhaps you would like students to start wherever they are and just keep learning and moving forward. Such a path will look different for each student, so sites or programs that either provide an sensibly ordered playlist (e.g., OWL Purdue Resources) or adapt based on student responses (e.g., Prodigy, FreeRice) or provide a blend of the two (e.g., DuoLingo, which is set up like a playlist but doesn’t let you continue after you incorrectly answer a certain number of questions) handles that work for you. Once you’ve learned how to effectively use these sites and programs in the virtual learning space, you may wish to continue using them once you return to your typical teaching situation. I encourage you to use them to help you effectively differentiate! Let’s talk about what that could look like. How might this translate when I’m back in the physical classroom? What I Need (WIN) time. Some teachers call this independent student work time. Some teachers may include a station rotation element. All it requires is making time for your students to work on whatever it is they need to work on (i.e., to catch up to grade level, to extend their thinking further, to work in a small group with a teacher). Differentiated homework. If students do have access to the necessary tech at home, you could assign these programs as homework in lieu of whole class homework assignments. (See my previous post, “Should I give homework?” for more of my thoughts on homework.) If students do not have a device or WiFi at home, I recommend using WIN time during the school day to ensure students get the differentiated experiences they need. As I said, the list of resources I’ve curated is certainly not exhaustive. You probably have amazing free resources you’ve been using with great success. If so, please share them in the comments below so other educators can learn from your brilliance! As always, thank you for doing what you do for our kids. Let’s keep learning, growing, and figuring it all out together! As a result of schools closing due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many educators are now working from home. Initially, sleeping in during your typical commute time and wearing pajama pants all day may have been a welcome shift away from your fast-paced routine. Although, by now, you may have realized working from home comes with it’s own unique set of challenges: finding it hard to focus, replying to dozens of messages a day from parents or students asking questions about tech or your instructional materials, and dealing with increased anxiety about the virus, your students’ well-being and your physical confinement. Sure, you love your family, but being in close proximity for weeks on end is challenging! As an instructional coach who regularly works remotely, I am familiar with these challenges, and I’ve developed a few routines to address them What does well-being entail? The National Wellness Institute’s 6 dimensions of wellness are: physical, social, intellectual, spiritual, emotional, and occupational. They state, “wellness is an active process through which people become aware of, and make choices toward, a more successful existence.” This description provides us with a sense of control, which is particularly important in moments of crisis. We can take stock of our well-being in each dimension, identify the areas where we would like to invest more energy, and decide how we want to build up that dimension of wellness. Each person’s wellness priorities and specific well-being practices will vary, but let’s look at some examples of what well-being practices could look like. Physical Well-Being As a teacher, I was used to moving my body all day, every day. The transition to largely sitting at a desk each day was challenging. I realized I am not at my best (physically or mentally) when I sit all day. So, I’ve tried to find a way to move my body everyday. I’m a runner, so I try to go for a run every other day. Other days, I’ll stay inside and do an indoor workout—this doesn’t need to cost money. I often do some body weight squats and push-ups (from my knees, no shame here!) or simply shake out my limbs for 10 seconds at a time. Some days, I just walk in circles around my very small apartment or walk up and down my apartment building’s stairwell as I try not to touch the railing. When I was teaching full time, I never hydrated well enough. That’s still true for me today, so I try to combine my movement breaks with my hydration efforts and regularly get up to refill my cup with water. Social Well-Being This is probably the most challenging dimension of well-being for me. I’m definitely an introvert, and I often say no to group hangs. Usually, I say this is because I want to practice self-care and conserve my energy. I’ve been invited to Zoom social hours, and so far, I’ve chosen not to go. At times like this, I feel like my preference to read a book by myself indicates there is something wrong with me. However, I have enjoyed work-related socializing like co-facilitating virtual workshops for teachers. This is solidly more in my comfort zone. I think it’s okay to combine a social well-being practice with another dimension like intellectual well-being. It doesn’t need to be co-facilitating or co-teaching either. It might be a virtual book club that meets via video chat. I have noticed seeing people’s faces and hearing people’s voices gives me a greater sense of connection than texting or commenting on social media posts, but, fellow introverts, we can choose whatever means of connection works for us! Intellectual Well-Being I’m a very goal-oriented person, so each year, I set a goal for the number of books I want to read. Lately, my reading goal has kept me reading more than watching TV (which is so much easier to do!) I track my progress on the Goodreads app, as part of their annual reading challenge. I try to read each day, before bed and sometimes for just a few minutes in the morning to help my eyes and mind adjust to being awake. A colleague asked me what I learned about myself after completing my 100-book challenge in 2019, and it was fascinating to hear my own answer. I discovered I had a passion for reading the memoirs of female comedians. I learned a bunch of new words. Now, I feel like I’m designing a literature course just for myself as I pick my upcoming reads. One hiccup in my plan to read more during the corona virus quarantine is that my local library is closed. So, I rely on BookMooch, a site that lets you exchange books with other readers just for the cost of shipping. If and when I run out of books, I have found watching documentaries, doing online crossword puzzles, and watching old Jeopardy episodes on Hulu has kept my brain feeling nourished. Spiritual Well-Being Spiritual may be religious, but it is also more broadly defined as one’s “sense of purpose” or “meaning in life,” (National Wellness Institute). I’m not religious, but I typically have a strong sense of purpose. Although, I have to admit, during this pandemic, when the parts of my job that include in-person teaching and facilitation have all been cancelled, I have had to do some soul searching about what it is I’m doing here. I’ve had to step back and ask myself why I’m in this line of work, what I can offer in this moment, and remind myself that the struggles I’m facing are strengthening my character. I often refer to VIA’s 24 values or “character strengths”, which I used to use with my high school students, to identify which value I’m being challenged to strengthen during this time. I try to talk to myself as if I were talking to a student, with empathy, but also with encouragement to adopt a lens of resilience or a growth mindset. I’m surviving. I’m strengthening parts of myself that haven’t been pushed in this way before. Emotional Well-Being I also teach myself to use the same self-regulation strategies or mindfulness techniques I have invited my students to use. Lately, my favorite breathing technique has been: smell the flower, blow the bubbles. When I’m having a serious bout of anxiety, I like to use Stop Think Breathe, which is an app that guides you through breathing exercises. (There’s an adult version, but I sometimes use the kid’s version because I love the simplicity, and it makes me feel like I’m in my own classroom again.) I try to monitor my emotions and energy level as I support my current college students in the transition to remote learning. I’ve decided to set boundaries around how and when I will respond to student questions. I find I’m most effective and empathetic to questions when I check my email only once a day, and offer the option to sign up for virtual 1:1 support during two, 1-hour blocks of time during the week. Occupational Well-Being As educators, we want to do a good job for our students, which can feel difficult in this time of school closures and potentially transitioning to online teaching. To support you in making this shift effectively, I’ve created a series of blog posts on adapting to school closures, which I’ve been posting for the last few weeks. I’ve used these posts as a way to synthesize my ideas, research, and experiences to help me plan how to support my current students during this challenging time. The biggest thing I’ve learned throughout all of this, is I am most successful when I make it a routine. One of the hardest things for me to remember is to move and drink water, so I start the day with 6 bracelets on one wrist and gradually move them over to the other wrist as I finish a new glass of water. I also make colorful trackers with paper and markers to track my progress with my other goals. It feels really good to take note of my progress, no matter how small, each day! Want an example of a well-being practices tracker? Click the button below for a free PDF. Just as we create and put plans in place for our students to ensure they are well, we can do the same for ourselves as educators! Research indicates teacher burnout predicts student academic outcomes and is correlated with lower levels of student motivation and increased student stress (Lever, Mathis, & Mayworm, 2017). Taking care of our own well-being enables us to be more effective as we support our students. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed