|

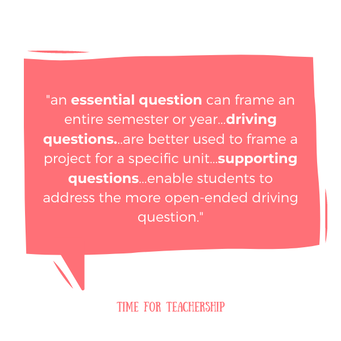

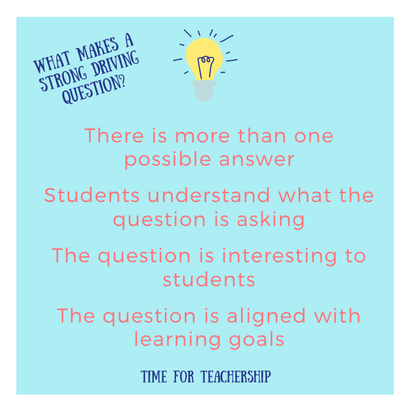

This past week, I wrote about the importance of student engagement and teaching for racial and gender justice as a powerful opportunity to engage students in academic learning. If you haven’t read those yet, I recommend starting there to better understand the context and the why behind the next several blog posts, which will focus on aspects of curriculum design. (You can read “Promote Student Engagement + Teach for Justice” here and “Why Teach for Justice?” here.) As I continue to discuss curriculum design, I will use a project-based learning approach. This is because research indicates project-based learning (PBL) enhances student engagement, student motivation to learn, student independence and attendance, content understanding and retention, and even test scores compared to traditional, non-project based, teaching (BIE Research summary). According to PBL Works, one of the “Gold Standard” elements of PBL is: a challenging problem or question. Let’s take a closer look at this element. Is a driving question the same as an essential question? Grant Wiggins, co-author of Understanding by Design, distinguishes between an essential question, a compelling (i.e., driving) question, and a supporting question in this blog post. He clarifies that an essential question “recurs over time” and “points toward important and transferable ideas,” while a driving question is rooted in specific content. Supporting questions “have agreed-upon answers” and “assist students in addressing their compelling questions.” All of these question types are valuable, but they all serve different purposes. By virtue of being broad, an essential question can frame an entire semester or year. Because driving questions are grounded in content and they require application of content understanding, they are better used to frame a project for a specific unit. Finally, supporting questions help us check for factual understanding and provide scaffolded support to enable students to address the more open-ended driving question. This synthesis of ideas from Grant Wiggins and Debbie Waggoner does a great job of clarifying these differences with examples (Bush, 2015). What makes a strong driving question? A strong driving question is key to the success of a project-based unit. If students are not excited to address the question, the project immediately becomes less effective. A high-quality driving question should meet the following criteria:

As you review or create a driving question for an upcoming unit, use these criteria as a checklist to make sure your driving question is strong. If it doesn’t meet these criteria, rewrite at least 5 iterations of the question, and pick the one that best aligns with the criteria. If none of your drafts check all of the criteria, keep drafting until you get there! Don’t be afraid to ask for feedback from teachers and students. Let’s look at an example. It can be difficult to write a strong driving question, so we’ll examine a concrete example. Let’s say I’m designing a unit for a Social Studies course entitled, Revolutions Through History. The unit is about the American Revolution. I draft the following three questions:

Looking at these three questions, I like the middle one best for a driving question. It’s grounded in specific historical content, it’s debatable, and it’s fairly straightforward, and students have to deeply understand the content to address the question with any nuance. The first question I drafted would make more sense as a thematic question for the year. For any unit, any revolution we talk about, during the year, we could always return to this question. We could even use the unit’s driving question to inform a response to this essential question. For example, if a student says it wasn’t revolutionary because it only grants specific rights to white, land-owning men, they could then say a necessary ingredient to a revolution is inclusion of all social groups in the revolution and subsequent policy creation. Finally, the third question is more of a scaffolding question. Let’s say all of my students say, of course it was revolutionary, it’s in the name: American Revolution. I might want to push their thinking by asking a factual question like this. Simply putting a question like this out there can help students come to see different perspectives and formulate new or more complex arguments. For more examples, John Larmer, editor of PBL Works and co-developer of the Gold Standard PBL model, has a great article on the difficulty of crafting an engaging driving question. In it, he shares several sample questions and talks about the two main types of questions: debatable questions and solution-generating questions. Lastly, if you’re interested in a worksheet to help you draft your driving questions, click the button below to get this week’s freebie. Happy question drafting!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed