|

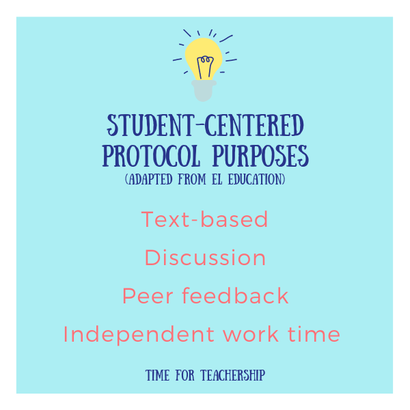

Protocols, also called activities, procedures, or learning routines, are the structured ways in which students engage in learning. For more background on protocols, check out this previous blog post. I specifically advocate for student-centered protocols, which ask students to grapple with the work and require very little, if any, direct teacher involvement. Of course, teachers can always support students as needed during protocols, but students benefit from the grappling when they are engaging in an activity within their zone of proximal development (e.g., they are able to accomplish the task with some peer support or scaffolded questions built into a protocol). For example, a well-built SMART Goal Template makes it possible for students to independently set and track thoughtful goals far more effectively than simply asking students to set a goal and track their progress without the scaffolding built into the protocol material. How many protocols should I use? One of the key ideas for making planning and teaching manageable for teachers and students is identifying a few high-leverage protocols that serve a handful of different purposes, and re-using them again and again. The re-use of protocols enables you to spend less time making new materials or teaching new directions for class activities. It also provides consistent, predictable routines for students, which frees up brain space to focus on the learning itself because they’re not wasting energy learning a new protocol. In science speak, it reduces the cognitive load. I like EL Education’s recommendation of having three to five go-to protocols that span a few different purposes. This is just enough for about one protocol per key purpose. Of course, you can always rotate in a new protocol to mix things up, but “mixing it up” too often can lead to student confusion and shut down. What may seem very repetitive to us as teachers can be reassuring and engaging for students. What are the different “purposes” protocols serve? EL Education shares the following protocol purposes on their site: text-based, discussion, peer feedback, decision-making, and presenting. When I think about these purposes in terms of how I used them in my class and how I’ve supported teachers in using protocols in their classes, I would adapt this list slightly to focus on the first three (text-based, discussion, and peer feedback) and I would add independent work time as another protocol purpose. The EL curriculum includes one hour daily of what is effectively a differentiated station rotation, but most teachers don’t have that time baked into their schedule, and thus would need to fit that into regular class time. If you can identify one go-to protocol for each of these—four total protocols—I think that’s all you really need. Your content or your teaching style may make you gravitate to one of these purposes more frequently than the others, and that’s okay! You can have multiple protocols for your most-used purpose. For example, in my high school class, I had two core discussion protocols, but used them in different ways and at different rates. I used circle protocol weekly, mostly for current events discussions and community building. I used the more content-focused Socratic Seminar, which enabled students to practice collecting and analyzing evidence to form and present academic arguments, about once a unit. Can protocols be used during distance learning? Absolutely! Student-centered protocols are great for distance learning, as they promote student independence and if well-designed, do not require direct teacher intervention. You may want to use different protocols for distance learning than you would in a physical classroom, but you can also adapt an in-person protocol for online use. For example, a gallery walk is a great text-based protocol. Instead of physically walking around a room and writing on chart paper, you might instead have students use a Padlet, with each column representing one “chart paper” or station. Alternatively, you could set up a Google Slide presentation for students to add digital post-its to a “digital chart paper” (i.e., a slide). EL Education suggests a virtual protocol called “Pass the Mic” for share outs in virtual class meetings, which essentially asks students to volunteer to share with the class by umuting, sharing for no more than 60 seconds, and then saying “I’m passing the mic to _____.” That student then unmutes and continues the process. This just simplifies the structure of the share out a bit, and can be used with many other protocols that have a whole class share out component. EL’s sample virtual learning norms are also worth a look as we think about how to build a virtual class culture for student engagement and discussion. (The norms are linked on this page.) As you decide which protocols you will use this year, and how you will adapt them for digital spaces, remember to keep the students at the center. Choose protocols that will enable students to do the work without your intervention, perhaps in partners or small groups so they can work collaboratively and help each other out. (To do this in a virtual space, you could use breakout rooms during a whole class meeting, or you could set up meetings with small groups of students in exchange for fewer whole class meetings each week). Finally, centering students in the learning process also means asking students to weigh in on what is working for them and what is not. Typically, I’ll ask for feedback on a protocol once I know students understand and can do the steps of the protocol, so that I know the feedback I’m getting is really about the learning potential of the protocol and not the students’ unfamiliarity with the protocol steps. Sharing your go-to protocols with other teachers on our Time for Teachership Facebook group or in the comments below is always welcome. This way, other teachers draw inspiration from you, and you can get inspiration from others!

1 Comment

Brian Hanlon

7/23/2020 08:54:23 am

Lindsay,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed