|

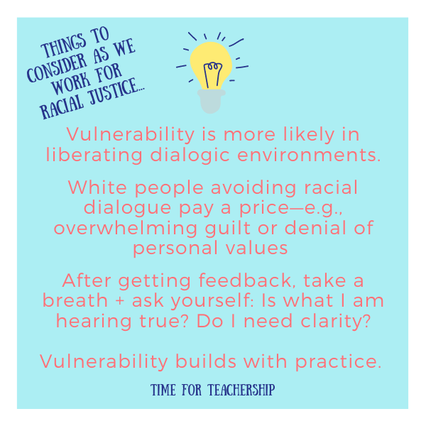

6/29/2020 At the Intersection of Racial Justice in Education, 4 Keys to Talking About Racism in Schools: #3 VulnerabilityRead NowThis is part 3 in our 4-post series featuring Dr. Cherie Bridges Patrick’s research on the four capacities that enable us to have generative racial dialogue. You can read Part 1 here, which focused on the importance of a positive, encouraging, liberating dialogic environment and Part 2 here, which focused on a readiness and willingness to engage in antiracism and racial justice work. Today’s post will focus on our recent discussion about the third discourse capacity: vulnerability. To define vulnerability, Dr. Bridges Patrick uses Brené Brown’s (2006) grounded theory work on shame resilience in women, in which she refers to vulnerability as being “open to attack.” As mentioned in the previous post, antiracist work is not without risk. Dr. Bridges Patrick writes, “the characteristics of facing vulnerability and risk include ability to trust (in the process, people, or one’s own ability), and ability and willingness to articulate fears and internal conflicts” (2020, p. 167). Vulnerability in the context of racial dialogue is more likely to happen when the discourse environment has been sufficiently prepared. Part 1 of our 4-post series offers a description on the dialogic space. A white participant in Dr. Bridges Patrick’s study reflected her fears, first related to her ability to carry out the work then on the impact that calling out racism at work can have on one’s collegial relationships, saying: “I have a fear of if I get into this what is that going to entail, it’s going to be a lot of work. And also to be perfectly honest, how are my coworkers going to look at me if I’m always the one bringing this up, and . . . can I take that on myself? I shouldn’t be putting it on other people to bring it up . . . everyone individually should be doing it, but it’s hard and you don’t want to be that person.” When talking about race, vulnerability seems particularly difficult for white people. Why? There are numerous perspectives as to why vulnerability is a particular challenge for White people. Some readers are aware of how Robin DiAngelo describes the phenomena in her book, White Fragility. She writes “As I move through my daily life, my race is unremarkable. I belong…It is rare for me to experience a sense of not belonging racially, and these are usually very temporary, easily avoidable situations” (2018, pp. 52-53). DiAngelo suggests that people who are Black, Brown, Indigenous, and Asian do not have this luxury, rather they have been forced into situations of discomfort, where they are “open to attack.” DiAngelo also gives an example of the ease with which white people can opt out of chances to exercise vulnerability, stating, “Many of us can relate to the big family dinner at which Uncle Bob says something racially offensive. Everyone cringes but no one challenges him because nobody wants to ruin the dinner...In the workplace…[we want] to avoid anything that may jeopardize our career advancement” (p. 58). These are examples of white solidarity which uphold white supremacy. White people need to make the conscious choices to put ourselves into these situations. Dr. Bridges Patrick offers her perspective on why vulnerability is so difficult for White people. There is so much to respond to in these two very rich statements by DiAngelo although, I will limit myself to two comments. I posit that it is not a luxury for White people to remain absent from racial dialogue. I do acknowledge the material and psychic gains that Whites regularly receive, yet at what cost? Those who have been sincerely interested in antiracism work, have likely, at times, experienced overwhelming guilt or have denied personal values in exchange for the acceptance of family and/or social values, for example. White people are concerned with being perceived as racist (van Dijk, 2008). In my work on racism denial, a strategy of defense often presented by Whites is positive in-group presentation, or face-keeping (van Dijk, 2008) that is performed to present an image of ‘not-racist’ or an image of goodness. Denial is also used to accentuate peoples roles as competent, decent citizens (van Dijk, 1992). Both arguments as to why vulnerability for Whites remains impenetrable potentially end up with the same or similar results yet the strategies to get there are different. When we make ourselves vulnerable, sometimes we may receive critical feedback. What’s an appropriate response? The work of antiracism absolutely requires feedback so we would be wise to welcome it. How we respond to feedback that others have been negatively impacted by our words is critical. Dr. Bridges Patrick offers this perspective: when feedback stings (and it will) before I verbally respond, I first pause, take a deep breath, and notice what is happening in my body. The first questions I ask myself are “is what I am hearing true?” and “do I need clarity?” Responding with tears, defensiveness, or hostile body language does little to further generative conversation, although it can invite other participants to return to the shared agreements that were developed at the beginning of the conversation. The purpose of feedback is to challenge patterns of thinking and behavior and to support growth. That’s the goal—to be better not to remain stagnant and steeped in the “smog” (Daniel Tatum, 1997) of racism we all breathe. How do we build up our capacity for vulnerability? Dr. Bridges Patrick says we need to “[grapple] with conflicting values and perceptions, particularly how [we] might be perceived by peers” (2020, p. 208). Discussions around race and racism engender emotions...remember that “race is a construct with teeth” (Menakem) while racism continues to wreak havoc on our lives, relationships, systems and souls. This means we must practice in those liberating dialogic environments or with an accountability partner. If we think about what has contributed to difficulty with engaging in productive conversations around race we find that many White people have not been having them, and quite honestly, some of us would rather not have them. When race becomes a topic, the example below is a common way race is brought up by White professionals in the workplace. Sophia, an African American, is responding to the question of when race comes up at work: “It comes up when there’s a problem, or, and I shouldn’t say a problem, but a challenge. So . . . let’s say there’s a patient who’s having some issues with safety in their neighborhood, then it’ll come up and somebody will say for example— because we level our community—so level one, high alert safety is really concerned about the neighborhood. So they’ll say, well, this patient is new to me and now, I’m not, you know, please don’t take this the wrong way, I’m not saying it’s because she’s Black you know, so that’s how it usually comes up.” How do we support our students to increase their capacity for vulnerability? Building our own muscle for generative racial dialogue is one of, if not the most important element for supporting increased capacity for students. In the first post of this 4-part series, we included a free resource to help teachers set class agreements that would support fruitful conversations about race and racism. In White Fragility, DiAngelo highlights common discussion agreements that she says are ineffective. As teachers, we can spend some time here, clarifying through class discussions what we as a class mean by our co-constructed agreements. For example, DiAngelo says “assume good intentions” is a problematic agreement because it positions intent over impact (not to mention that intent cannot be substantiated and is often used as a strategy of denial). Donna Hicks’ seventh element of dignity offers an alternative, “Benefit of the doubt.” While these two points might at first glance seem contradictory, they are not. We can, as Hicks says, “Start with the premise that others have good motives,” while also focusing on impact over intent. As educators, we want to make time for these important conversations about nuance with our students, so they can effectively engage in conversations about racism. Using what you’ve learned in this series and in other readings about antiracism work and racial dialogue, start making a list of points or clarifications you want to bring up when you and your students develop your class agreements together in the fall. Although only class agreements are mentioned here, in any planned group racial dialogue there should always be a discussion around rules of engagement. A perspective offered by Dr. Bridges Patrick notes that “one of the ways I start that particular conversation is to first position dignity and honoring each person’s humanity as non-negotiables. I then ask the question: What do each of you need to have honest, vulnerable conversations about race and racism?” As Dr. Bridges Patrick eloquently writes in the closing to her dissertation, “dominance does not sleep nor does it vacation, rather it feeds off of fears and ignites the propensity to look away from its reality. Simultaneous to this is the silent presence of resistance that must also receive attention” (2020, p. 218). Thus, we must look inward to deeply reflect on our values, refuse to look away, and build our capacity for resistance.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed