|

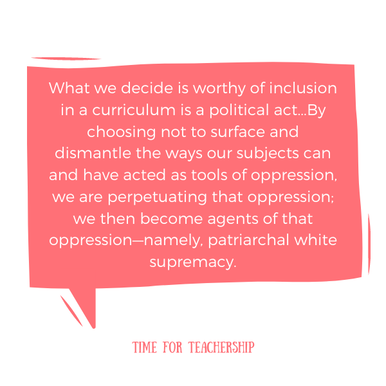

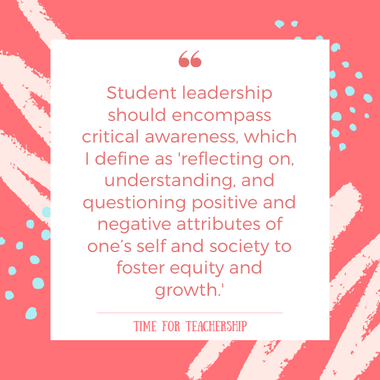

In her book Reading, Writing, and Rising Up, Linda Christensen begins the first page with, “Why reading, writing, and rising up? Because during my 24 years of teaching literacy skills in the classroom, I came to understand that reading and writing are ultimately political acts.” She goes on to write about how historically, enslaved people in the U.S. were denied opportunities to learn to read and write and in more recent history, government funds are spent on things like going to the moon rather than investing more resources in education while the racialized opportunity gap persists. Curriculum is Not Neutral I agree with Christensen. How and what we teach in literacy, history, math, science, art, physical education, technology...all courses...is inherently political. What we decide is worthy of inclusion in a curriculum is a political act. History and literacy are often cited as the subjects in which it’s easier to address issues of injustice, but unpacking how math and science are applied in practice is a powerful opportunity to examine how STEM concepts can and have contributed to racial and gender inequity, even today! Furthermore, we can introduce students to ways math and science (and literacy and history and art and PE) can be applied in ways that advance racial justice. By choosing not to surface and dismantle the ways our subjects can and have acted as tools of oppression, we are perpetuating that oppression; we then become agents of that oppression—namely, patriarchal white supremacy. Learning About Relevant Issues is Engaging Another reason to center issues that impact students’ lives in our curriculum is that it amplifies student engagement. Christensen writes, “I couldn’t ignore the toll the outside world was exacting on my students. Rather than pretending that I could close my door in the face of their mounting fears, I needed to use that information to reach them” (p. 4). Here’s the thing: all students want to learn. But, it’s hard to engage with a curriculum that is just not interesting. As educators, it’s tough to engage all of your students—some teachers have hundreds of students to engage! And to be perfectly clear, I did not and still do not engage 100% of my students every day, but once I started designing units around issues relevant to my students, the number of students I was able to engage was far higher than when I was teaching from a textbook. To ease the minds of teachers nervous about going off-book, Christensen writes, “I want to be clear: Bringing student issues into the room does not mean giving up teaching the core ideas and skills of the class; it means using the energy of their connections to drive us through the content” (p. 5). How does community building fit into this? When teachers ask what they can do to increase student engagement, I often share two key ideas: build a thriving classroom culture and design engaging curricula. Christensen notes both are necessary, pointing out that one informs the other. She says, “Building community means taking into account the needs of the members of that community. I can...play getting-to-know-each-other games until the cows come home, but if what I am teaching the class holds no interest for the students, I’m just holding them hostage until the bell rings” (p. 5). Building relationships is a critical piece of engagement because it enables us to be more effective educators. To Foster Justice-Oriented Student Leadership Something I often hear in education is the importance of educating “future leaders.” While I insist students can and should be leaders while they’re still in school, to be effective leaders, as youth or adults—students need to learn and practice leadership skills. And the type of leadership we support in students to practice is critical. As a leadership scholar, I can tell you there is far less scholarship on student leaders than on adult leaders. In my research, I suggest we specify the kind of leadership we’re trying to foster in students. Specifically, I posit student leadership should encompass critical awareness, inclusivity, and positivity. Let’s take a closer look at how I define that first one—critical awareness: “Preskill and Brookfield’s (2009) book on social justice leadership as well as the self-awareness and self-development tenants of authentic leadership (Walumbwa et al., 2008) contributed to this study’s definition of critical awareness as reflecting on, understanding, and questioning positive and negative attributes of one’s self and society to foster equity and growth.” (Lyons, Brasof, & Baron, 2020). By this definition, students with the capacity to be critically aware are focused on working towards equity and are able to critically reflect and question information and events as well as their own thoughts and actions, all in service of personal and societal growth towards racial and gender equity. This is what I hope for all of our students and leaders, but this capacity doesn’t just happen. It takes work to enable it to flourish. We can help students do that work. If you’re interested in teaching for justice but overwhelmed by the idea of building units from scratch, I have something for you. In just over a week, I’m offering a free 1-hour online masterclass where I’ll be sharing my biggest secrets on creating brand new units. Click the button below to save your seat in the masterclass.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed