|

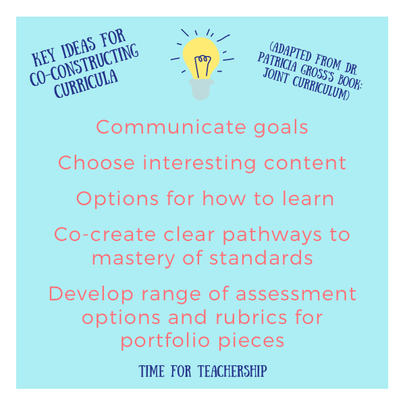

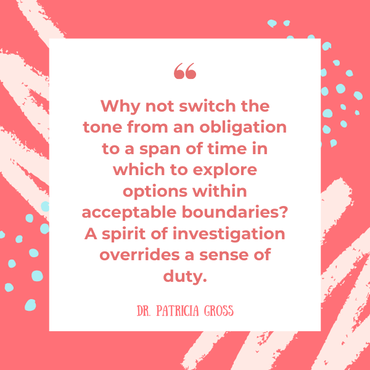

In my review of the literature on student voice, I have attempted to catalogue what I call “mechanisms” that amplify student voice in educational spaces. One of the mechanisms I have identified is “pedagogy,” a very broad mechanism that encompasses several key practices, including: scaffolding, discussions of social injustice relevant to students, flexible space (i.e., co-creating learning spaces with students), and co-constructing curricula with students. It is the latter practice, rare but powerful, that this post will address. The notion of co-constructing curricula sounds intimidating at first, but I think it’s much more accessible and actionable when we think of it as a continuum. Teachers who have been co-constructing curricula with students for a while are going to have much more fluid and flexible planning practices than teachers who are trying it out for the first time, and that is completely okay. I want to spend some time talking about what co-constructing curricula is and what that could look like in your classes. To help frame this post, I use the work of Dr. Patricia Gross. Specifically, I share insights from her book, Joint Curriculum, which details the stories of two teachers who enlisted her help in shifting their teaching and planning processes to co-construct curricula with their students. Gross describes what is involved in joint curriculum design as follows: “(a) Students and teachers who communicate goals, envision and strive toward common aims; (b) they mutually interrogate what content choices stimulate inquiry through individual and group interests; (c) they negotiate methods of how to proceed to accommodate individual needs and learning styles; (d) they collaborate to sequence when sufficient exploration and practice lead to comprehension; and (e) they devise assessment criteria to specify why to inquire into topics and determine expected outcomes” (1997, p. 5) [emphasis in original]. In Gross’s bolded words we see some key ideas of co-constructing curricula. It involves communicating with students about the goals of the class (and recognizing that each student’s goals may be slightly different). It involves figuring out what specific content is interesting and relevant to students (again, noting that interest level will not be identical for all students). It involves a conversation and perhaps a provision of options to students about the class protocols, “text” choices, and perhaps tech tools that are available for students to engage in learning course content and skills. It involves a co-construction of a clear path to mastery of a particular skill or content understanding with the flexibility for learners to move at the fastest pace that they are able to move without disrupting comprehension. It involves a degree of co-construction of a project-based, perhaps course-long, rubric (e.g., the course priority standards and what success looks like at each level of mastery). This assessment piece also involves providing a range of assessment options, so that students’ grades are reflective of a portfolio of work, the pieces of which they should be able to revise and resubmit. One place along the continuum of co-constructing curricula with students is the use of Genius Hour, also known as 20% Time. This strategy gives students 20% of class time (maybe one day a week or one hour a day) to work on projects of their own design. I was fascinated with this concept in my last year of teaching, to the point in which I tried doing a Genius Hour semester, all day, every day! After testing it out, I would not recommend such extreme fluidity for such a long duration. However, during the first 2 months, students were incredibly energized by their work! For example, projects that were created in that semester included: student-designed t-shirts to raise awareness of problems facing the LGBTQ community and incarcerated mothers; a video game a student created after learning a new coding language; 30-minute documentaries including one on the hypocrisy of the founding fathers and one on the importance of music; a student-designed field trip series, in which a student filmed visits to social justice art installations around the city; and a comparative essay written after reading two novels (this student wanted more practice before completing this task for their senior portfolio the following year). If you’re interested in starting Genius Hour with your students, I’ll re-share a template I used for the first few days my students engaged with this project. Just click the button below to access it! (Also, if you missed my masterclass this week, sign up for a spot next week, where I’ll be sharing how you can get my entire Google Drive folder of Genius Hour resources.) Of course, you don’t need to start Genius Hour to co-construct curricula with your students, you can simply ask for their thoughts more often (and then use that information to adjust your planning.) I love Gross’s point that, “Joint curriculum design values teacher expertise. However, teachers impart information sparingly to pique students to verify or question information to draw and substantiate their own conclusions” (p. 29). So, we can create a unit, and begin implementation, but leave some space (perhaps in the form of choice boards to explore content subtopics or open-ended projects options) for students to run with whatever piqued their interest. At first, my students were wary about co-constructing curricula. I was met with initial resistance (by some students, not all) in the form of “Just tell me what to do, Miss.” This saddened me, but when students have experienced education as being told what to do and having little voice in that process for so long, it makes sense to me why that was their initial reaction. For these students—there were several in each class—we formed a small group to brainstorm ideas together. After asking what interested them and getting no responses, I threw out some possible options for discussion, and they chose one and adapted it as they went. I will say those students were less enthusiastic about their projects than the other students, and this realization reinforces my conviction that student voice in the co-creation of learning experiences is critically important at all ages of learning. Students enter school as 4 or 5 year olds, curious about everything! If we consistently teach without consulting and co-creating with students, that curiosity fades more and more each year. Gross points out that students are mandated to be in your class, but she poses this question for thought: “Why not switch the tone from an obligation to a span of time in which to explore options within acceptable boundaries? A spirit of investigation overrides a sense of duty” (p. 59) [emphasis in original]. I love this concept of exploring options within acceptable boundaries. While it may be intimidating, remember it’s a continuum. Determine what degree of co-construction you’re ready to test out, and plan with choice and flexibility in mind. Given the decreased levels of engagement many teachers have seen during distance learning this past school year, I think this approach is definitely worth a shot.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed