|

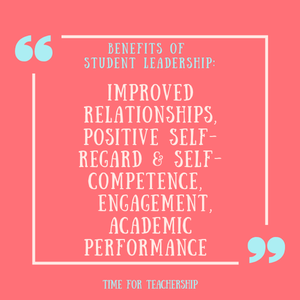

As we move towards more student-centered learning models in education, we may hear the term “student voice” more often. I hear it a lot in reference to giving students literal voice via talk time during class or giving students opportunities to choose which of 3 similar activities they would like to complete. However, the scholarly research on student voice reflects a higher level of student autonomy than the way it’s being used in practice. What is student voice? Dana Mitra’s (2006) pyramid of student voice reflects three levels of student voice. At the bottom, we’re listening to students. We might survey them once in a while, but the student involvement stops there. At the middle level of Mitra’s pyramid, students work with adults in partnership to accomplish school goals, maybe as part of a school committee or after school club focused on a particular initiative. At the top level is building capacity for student leadership. Mitra and Gross (2009) note student leadership is a powerful form of student voice, but quite rare in practice. The commonly accepted definition of student voice, put forth by Fielding (2001), is: students’ ability to influence decisions that affect their lives. I often adapt this during workshops with educators, embedding practical examples: Students have a voice in what, how, where, and when they learn. All Students as Leaders Unfortunately, in the instances where schools are offering opportunities for students to have a voice in decision-making and take on leadership roles, these opportunities are limited to the students who are already seen as “leadership material” by adults. The transformative power of student voice lies in all students having leadership potential. Lundy (2007) discusses barriers to inclusive, authentic student voice, and argues that to overcome these barriers, students need the following: the ability to form their ideas (which may require adult support in skills training or sharing information to help students arrive at an informed opinion); space to express their ideas; adults to listen; and the influence to inspire action (or at least receive explanations as to why action was not taken). Taking into account the importance of support from adults and school structures in helping all students fulfill their leadership potential, I created the following definition of student leadership: students working collaboratively to affect positive change in their educational environments with support from adults and mechanisms in the school (Lyons, 2018) Why promote student voice and leadership? Research has found lots of benefits to student voice in schools. Individual students who engage in leadership activities, have demonstrated improved peer and adult relationships (Yonezawa & Jones, 2007); positive self-regard, feelings of competence, student engagement (Deci & Ryan, 2008) and academic performance (Mitra, 2004). It’s not just individual students that benefit. The school as a whole benefits too! Additionally, when the decision-making process of an organization includes diverse stakeholder involvement, organizations make better decisions that result in improved organizational performance (Kusy & McBain, 2000). Students acting as representatives of various student groups also energize students that identify with them. Feldman and Khademian (2003) call this “cascading vitality.” Essentially, students inspire and empower others, lifting up students that may be experiencing structural, political, and/or social marginalization. Baumann, Millard, and Hamdorf (2014) remind us “preparation for active citizenship was a foundational principle of public education in America from its beginning” (p. 1). Not only should schools prepare students to be responsible leaders after graduation, we should provide authentic opportunities for students to be civically engaged while they’re still in school. Now that we’ve laid out the benefits of diverse students participating in authentic school leadership opportunities, ask yourself: How can I provide an opportunity for my students to have a voice in what, how, where, or when they learn?

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed