|

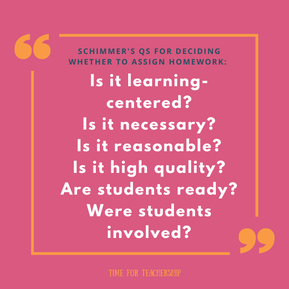

Homework prompts interesting debate among educators and educational scholars. Anecdotally, I found my students were successful with minimal prescribed homework. In this post, I want to review what the research says on homework and then share what I did in my class. What does the research say? One study found that students are spending much more time on homework than they were 20 years ago. Interestingly, there’s a gendered component here as well, with girls spending more time on homework than boys (Pew Research Center). Another study found students are receiving up to 3x the amount of recommended homework, and even kindergarteners (who researchers agree should not be given homework), have 25 minutes of homework per night (CNN). Does homework help students? It’s complicated. In Cooper, Robinson, & Patall’s (2006) meta-analysis, they found homework has a stronger positive correlation with academic achievement on standardized tests. The positive relationship was stronger in grades 7-12. They suggest homework may improve study habits, attitudes toward school, self-discipline, inquisitiveness and independent problem solving skills, but they note the empirical evidence on this is limited. They also warn that too much homework can be counterproductive. Should I give homework? Vatterott (2010)’s 5 hallmarks of good homework are that it is: meaningful, purposeful, efficient, personalized, doable, and inviting (Minke, 2017). It should serve a purpose, have meaning for students (i.e., connect to what students are learning in class), and relate to their interests and ways of learning). It should spark curiosity! This helps students love learning. The challenge should be appropriate, so make sure students can do this work independently. Not sure they can? Save the practice for class time, and assign the mini lesson for homework! The purpose is particularly important when designing your curriculum. ASCD emphasizes the importance of assigning purposeful homework, stating “legitimate purposes for homework include introducing new content, practicing a skill or process that students can do independently but not fluently, elaborating on information that has been addressed in class to deepen students' knowledge, and providing opportunities for students to explore topics of their own interest.” NEA lists homework purposes as: practice, preparation, extension, or integration. Schimmer (2016) suggests asking yourself the following questions when determining whether to give homework to students:

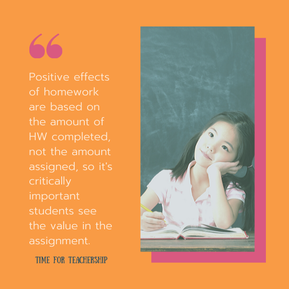

If you can say “Yes” to all of these questions, go ahead and assign the homework! If you answered, “No,” consider re-working the assignment, flipping the instruction, or skipping the homework for the night. How much should I assign? The general rule for calculating the maximum amount of time students should spend on homework each night is to multiply the student grade level by 10 mins. (For example, 3rd graders should have no more than 30 minutes of homework per night.) This is the total for all subjects, so if you only teach 1 subject, keep in mind your homework should take a fraction of that time (ASCD). Also, keep in mind that most of the research on homework indicates that the positive effects of homework are based on the amount of homework completed, not the amount assigned, so it’s critically important students see the value in the assignment, or they will not do it and there will be no benefit to assigning it. In fact, if that’s happening, I students are likely losing motivation to learn and seeing themselves as a “bad student,” leading them to further disengage. What should I do with completed homework? It depends on the purpose. If you’re assigning homework as a way to help students build study skills, just checking that it’s done should be enough. If the assignment is part of a larger assignment (like a rough draft of a paper), it’s helpful to give students feedback on their work as opposed to just checking that it’s done. Note the difference in purpose—work habits versus skill mastery. Walberg (1999) found teacher comments on homework to have a higher impact on students’ academic achievement than simply giving a grade (ASCD). In my classes… In my high school classes, I used homework as a time for completing project pieces they did not finish in class. So, my homework assignments had an integration or application purpose, and they were always started in class. The application element builds academic achievement, but it also teaches study skills and time management, as I would give students time to work in class, and then if they needed more time or worked inefficiently during class, they had homework. In my college classes, simply because we have less class time, I use a flipped classroom method, assigning readings/viewings as homework and then use class time for independent application or class discussions, so I can provide formative feedback and correct misconceptions during class. This also reduces my out of class grading time, as the feedback that Walberg (1999) found helpful to student learning, doesn’t always need to be written! When and what do you assign as homework? How do your students engage with it? Do you measure its impact on student achievement?

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed