|

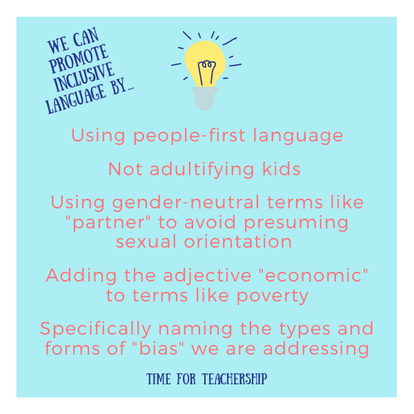

This post is the second of two on inclusive language in educational spaces. If you haven’t already, please go back and read Part 1, which introduces the importance of inclusive language and covers terms related to gender and race. Once you’ve done that, you can return to this post, which addresses what I’ve learned about language related to other axes of identity. Ability. People-first language is something to keep in mind for all descriptions of people. When referring to students with IEPs, we can use the term “students with IEPs” or “students with dis/abilities” (I use the “/” to recognize some dis/ability activists prefer terminology that is less deficit-based while other dis/ability activists prefer the term “disability”. As a teacher, I have gotten caught up in educational shorthand and said “SPED students,” but I want to eliminate that phrase because it’s not people-first language. Terms like “handicapped” and “cripple” are not acceptable terminology. When referring to a person who uses a wheelchair, we can literally say that (“uses a wheelchair”) or we could use a more general term like “a person with a physical impairment”. Of course, we don’t use phrases or allow students to use phrases to demean others, but I just want to note that terms like “moron,” and “idiot” originated as offensive terms used against folx with mental impairments. If we hear students use this language, we can explain why this is harmful for multiple reasons. Age. This one overlaps with race. White supremacists have infantilized and oppressed Black men in the U.S. through use of the offensive term “boy.” While this should be commonly understood as racist, a similarly problematic use of age-inappropriate terms may be affecting Black children in our classes. Studies have shown Black children are seen as older than their age compared to white children. This is called “adultification bias.” (While many studies have focused on Black boys, this is also a problem for Black girls.) This is particularly problematic as adultification bias often results in increased rates of discipline or increased use of physical force against Black children. LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer). When referring to a spouse or person that a student or family member or colleague is dating, using the term “partner” is more inclusive than “husband” or “wife” or “boyfriend” or girlfriend.” It encompasses all genders and does not assume the person’s sexual orientation. Also, when referring to families in a same-sex relationship or teaching about marriage equality, the phrase “same-sex” is preferred to “gay marriage.” Socioeconomic Status. My brilliant professor, Dr. Philomena Essed, helped me change my language from terms like “poor” and “poverty” to be more specific (e.g., “economically poor” and “economic poverty.”) The first set of terms implies a total lack of wealth beyond money—a lack of values, dignity, etc., but in being specific (adding the adjective “economic,”) we can uphold the person’s dignity. The term “low-income” also works here. Issues. When discussing students facing housing insecurity, rather than saying students are homeless, we can a student or family is “experiencing homelessness” or “experiencing houselessness” (this term acknowledges “home” is more than a physical structure) or “living in temporary housing”. Recently, I heard Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley say one of her constituents told her he preferred the phrase “food aparteid” in place of the more commonly used “food desert,” explaining people in his neighborhood are capable of growing their own food, but the system has not provided access for them to do so. Bias. Generic words like “bias” can sometimes be used to cover up specific injustices. If we don’t specifically name what we are talking about, we cannot address the oppression. Anti-bias training can be helpful, but without naming the specific ways bias is enacted (e.g., racism, sexism, homophobia) and the various forms oppression can take (e.g., interpersonal, institutional), it can lessen the impact of the work. It’s not that we have to throw out the term, we just want to be mindful about naming specific oppressions and not focusing on individual acts of bullying at the expense of tackling the policies and structures and systems that perpetuate the oppression. Finally, there are many phrases that I hope are so obviously inappropriate I don’t need to list them. Two that I thought were gone, but I’ve actually heard educators say recently include: “That’s gay” and “That’s retarded.” Let’s stop using these phrases. Instead, say what you actually mean (e.g., “That’s ridiculous.”) To help you keep all of these terms top of mind, I’ve condensed the big takeaways onto one page you can use as a quick reference. Of course, there are many examples I have not included in this list and far more I’m not yet aware of, so I welcome additional contributions in the comments below. I’m looking forward to growing and learning alongside my fellow educators.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed