|

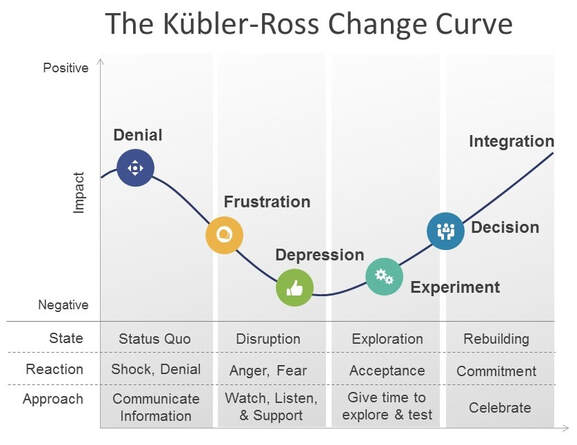

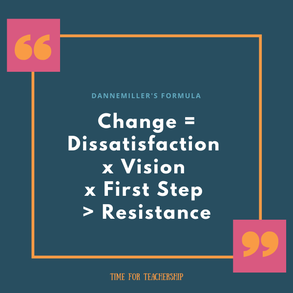

Principals, assistant principals, instructional coaches, school leaders, have you ever had an exciting idea that you just know will be so good for teachers and students, but the biggest barrier is a lack of buy-in from teachers? The phrase, “but this is how I’ve always done it,” may have become your greatest nemesis, right along with “I don’t have time for this.” Getting buy-in to a new initiative is hard work. In this post, I share 4 research-based strategies school leaders can use to effectively lead change. The first few suggestions may sound familiar. I’ll repeat them over and over because they are critical to successful change management. Have one clear vision. Choose 1-2 goals for the year (or more years—3 to 5 years is ideal for major initiatives). Research on Massachusetts turnaround schools found the schools who did not make gains lacked prioritization of a couple key areas, instead focusing on too many things at once (DESE). These 1-2 goals should be data-informed, high-leverage, and co-created with stakeholders or a representative stakeholder team. Manderschild & Kusy (2005) write about vision, citing Kouzes and Posner’s finding that a clear vision leads to “higher levels of [employee] motivation, commitment, loyalty, esprit de corps, and clarity about the organization’s values, pride, and productivity,” (p. 67). They also note it is important to measure progress towards the vision within performance evaluations. If it’s a priority, make sure your feedback to teachers and evaluation of their growth reflects that priority. Make space on teachers’ plates. We can’t add to teachers’ plates without taking something off. If it’s a priority, something else can go. I talk more about this in my post on how to support teacher leadership, where I share a free quick guide on how to carve out time in the school day for teachers to grow, learn, collaborate, and invest time in new initiatives. Next Tuesday, I’ll share a teacher-facing blog post to support teachers in re-thinking how they spend planning time to make space for individualized professional development. If it’s helpful, check it out and send it to teachers to help them make that shift. Connect with teachers’ hearts. The prominent adaptive leadership scholar, Ronald Heifetz, says, “What people resist is not change per se, but loss,” (Heifetz, Grashow, & Linsky, 2009). Teachers’ identities are tied up with their jobs. With the role of teachers shifting from “sage on the stage” to “guide on the side,” it’s reasonable to expect there may be a bit of a loss of identity. Ultimately, we want to help teachers see the value of this shift—that students benefit more when we teach them how to be learners not simply what to learn. However, immediately after introducing this shift, it’s important to empathize with and speak to that teacher identity and sense of loss. Use that to paint a picture of how the new initiative or vision speaks to their passion for student learning (because, if it’s a good initiative, it definitely will). If teachers don’t seem ready for a change, Anderson (2012) says, talk (and listen) to them, share the data to let them discover the issue and urgency themselves, and share research on the topic to lend credibility to what you’re trying to do. Just don’t forget the heart! Kotter & Cohen (2002) warn that many change initiatives fail because they rely too much on the data end of things instead of inspiring creativity by harnessing the “feelings that motivate useful action” (p. 8). The image of the Kübler-Ross change curve below may help you recognize where teachers are, emotionally, during the change process and how you can support them during each stage. Create dissatisfaction with the status quo. I love Dannemiller’s adaptation of Gleicher’s formula: change = dissatisfaction x vision x first step > resistance. This formula accepts that resistance happens, but it can be overcome as long as teachers can recognize their dissatisfaction with the way things are now, there is a clear vision for how this can change, and there are acceptable first steps we can take. These variables are multiplied, meaning if any one of them doesn’t exist, resistance will win (because any number multiplied by 0 is 0). If there is no dissatisfaction, leaders must create it! Mezirow (1990) notes adults need a disorienting dilemma to jumpstart transformative learning (learning that requires a paradigm shift and asks us to critically examine our assumptions rather than just learn a new skill). A disorienting dilemma forces us to examine our assumptions. Presenting teachers with information that makes teachers just uncomfortable enough to realize, “the way I’ve been thinking about this isn’t working anymore,” will help them try on other ways of thinking and be willing to rearrange how they see the world. This is most effective in the context of group dialogue, as folks are able to briefly “try on” others’ ways of thinking. So, go ahead and create a disorienting dilemma! Also, remember that major transformation is usually made up of a lot of little changes over time. You won’t shift mindsets in one meeting, but you can present the disorienting dilemma and let the disorientation start to sink in. When teachers are sufficiently disoriented, they will be seeking new ways of thinking, and you’ll have an opportunity to introduce those new ideas. To think about possible disorienting dilemmas for teachers, consider presenting a situation in which two values that teachers hold are in direct competition. For example: A teacher finds themselves working 60 hours each week to complete lesson plans and grade student work. This positions their personal well-being in direct conflict with their love for student learning. Let teachers recognize the discontent, explore the underlying assumptions, come to the conclusion that transformational change is the way to overcome the discontent, and start exploring different ways of thinking that could address this dilemma. Once teachers get here, you can take them through the final steps of making an action plan, testing it out, building capacity for this new approach (through PD, coaching, and other support), and integrating this practice into teachers’ lives and ways of being. (The summary, “Mezirow’s Ten Phases of Transformative Learning” has a bit more detail on the transformative process.) Change is difficult, and it takes time. These research-based ideas will get you started, but the real work is in how you bring teachers into the change process. Help me create resources that address your challenges with leading change! I would love to hear what challenges you’re facing and what kinds of change initiatives you are working on in your schools. Share any questions or success stories in the comments below, in our private facebook group, or by hitting reply to my latest email.

1 Comment

10/9/2020 11:43:46 am

Thank you for addressing that loss is one of the major factors in resistance to change.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed