|

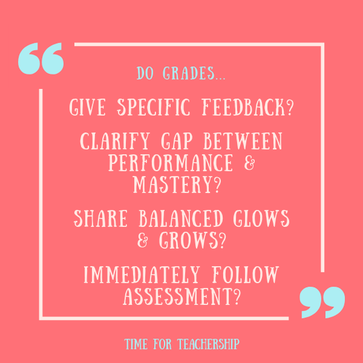

Inundated with grading? Most teachers are. Why? Because many teachers and administrators conflate the purpose of feedback and grades. In fact, that was recently the topic of an #edchat, which you can hear about on this 11 minute podcast episode if you’re interested. Feedback is information that helps students see where they are in their learning trajectory, and if it’s good feedback, it also helps students determine what to do next in order to continue to learn and grow. Grading is one form of providing feedback, perhaps the most common type, which evaluates a student’s proficiency. When we think about ourselves as learners trying to learn a new skill or hone a craft, we may say we value feedback that is very specific and helps us identify the gap between where we are and what competence or mastery of the skill looks like. We may also want the feedback we receive to be balanced, a healthy mix of what we are doing well and what needs more work. It is likely we would also want this feedback as soon as possible, so we don’t continue to make mistakes and can course correct quicker and see growth much sooner. If we think of these preferences as elements of quality feedback, let’s now consider which elements of quality feedback grades provide. Are grades specific? They can be, if a rubric is used, and specific skills are graded separately. Although, I’ve seen several rubrics that are quite general. For example, “Conventions” is a broad category. If I receive a low grade in this area of a rubric, it could be a niche punctuation error, like when to use an em dash, or it could be a variety of beginner level spelling and grammar errors that make the writing illegible. Those are very different problems. Do grades help us contextualize our skills in relation to what mastery looks like? They might if they are mastery-based grades (e.g., Below Standards, Meeting Standards, Above Standards). Not so much if the grade a number from 0-100 or a letter from A-F. Sure, we know a 65 or a D is acceptable, but is that “meeting standards?” The concept of a 65 as passing has historically been used for tests of factual recall. Is it acceptable that students only remember 65% of the information we have deemed important enough to teach them? Is that the standard we hold for our students? Forgetting almost half of the material? Alternatively, if a student answers 100% of fact-based test questions correctly, does that demonstrate they have mastery of our course content? Do we not want students to be able to creatively apply that information in a novel context? Are grades a balance of both “glows” and “grows”? Not in and of themselves. The narrative feedback that can accompany a grade does meet this criterion, but the grade itself does not. So, really, the narrative comments without the grade would do just fine here. Are grades timely? I suppose they could be, but typically no. Auto-grading multiple-choice quizzes or tests are immediate, but manually calculated grades are certainly not immediate (unless you grade the work during class and give it to the student right after they finish a presentation). Typically, teachers take anywhere from 1 day to a few weeks to get grades back to students. As we run grades through the filtering criteria of quality feedback, we can see that they barely meet any, let alone all of the criteria. So, what’s the answer? Formative feedback. As I’ve said before, providing immediate feedback during class has a strong positive impact on student learning. It helps students self-correct in the moment and can increase the speed of student learning by 70-80% (Hattie, 2012)! It also saves teachers time from grading student work after school and on weekends. How can you give that much formative feedback during class? I have a program that goes into much more detail (learn more by signing up for my free masterclass), but here are some quick tips:

Our educational system is steeped in tradition and as such, change has been slow. There are many K-12 school districts, some colleges, and even entire states, that have adopted more high-quality feedback systems than ineffective letter and percentage grades. Until your school comes around, I understand you need to play the game. I know that many schools require teachers to enter a minimum number of grades each week or each quarter. But here’s the thing: they require this because they want students (and family members) to get feedback on where they are in their learning journeys. Administrators may not realize there are more efficient and more effective ways of providing feedback. Let admin and family members know what you’re up to (i.e., giving better feedback, not abandoning feedback altogether!) Once students have a better understanding of their strengths and areas for growth, they can summarize what’s going on. Have students record a video explaining their recent feedback and send that home. Family members will likely learn a lot more about their child’s progress from a detailed video than they would from a simple number or letter. Breaking free of the “I have to grade everything!” mindset is a challenge, but it is so worth it—for your students’ learning and for your work-life balance.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

For transcripts of episodes (and the option to search for terms in transcripts), click here!

Time for Teachership is now a proud member of the...AuthorLindsay Lyons (she/her) is an educational justice coach who works with teachers and school leaders to inspire educational innovation for racial and gender justice, design curricula grounded in student voice, and build capacity for shared leadership. Lindsay taught in NYC public schools, holds a PhD in Leadership and Change, and is the founder of the educational blog and podcast, Time for Teachership. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed